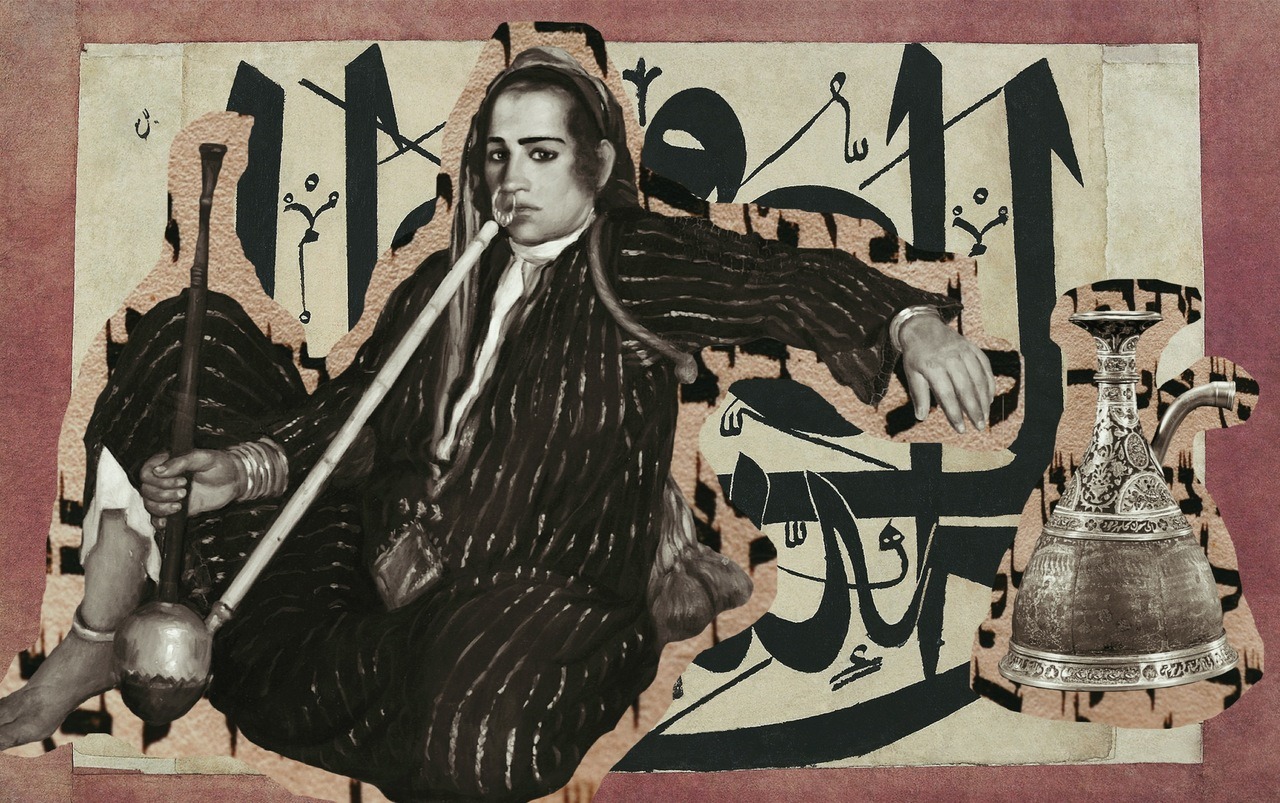

This piece originally appeared in ZAMAN, an arts & media collective dedicated to the remembrance, preservation, and re-evaluation of Mizrahi cultural consciousness.

Hashish, the emblematic, mystified drug of the Middle-East, is just hemp. Yes, the cannabis kind. While marijuana constitutes the buds of the flowering plant, hashish is made of its resin.

Since the inception of its recreational use in southwestern Asia, hashish has functioned as a hallmark of many vital literary works and cultural movements across history. In One Thousand and One Arabian Nights, one character is found sleeping in front of the city gates and guards approach him, asking if he had passed out because he was stoned. Some Rastafarians believe the burning bush that Moses saw was really an innuendo for cannabis. There is even a conspiracy that in C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe, the chocolates the Witch gives one of the children were actually laced with hashish, referring to them as “Turkish Delights.”

But how did this plant gain its status as one of the most popular drugs in southwestern Asia and the Maghreb? Turns out it all started with a cult of pothead assassins.

origins and distribution

From the mid-1050s to the mid-1270s, there existed a secretly-practiced sect of Shi’a Islam found in the Nizari Ismaili “state,” a network of settlements and fortresses in Syria and Persia. Nizari Ismailis observed a strain of religious practice they attributed to the ways of the descendants of Muhammad’s daughter Fatimah. The followers of this sect often took on the role of what we would today call assassins. As crusaders hailing from the north became increasingly present in the cities dotting southwestern Asia, members of this cult developed a practice of silently killing crusaders then retreating into hiding. The sect’s followers were called asāsiyyūn (أساسيون) which originally meant “faithful people,” but after a story formed about the group’s leader marketing hashish as an alleged entry ticket to heavenly transcendence, the members’ title was mistranslated to mean “men of hashish” or “hashish eaters.” By the time Shakespeare came around, he turned the Italian-influenced noun “assassini” into a verb (something he always loved to do), creating the words “assassinate” and “assassination.”

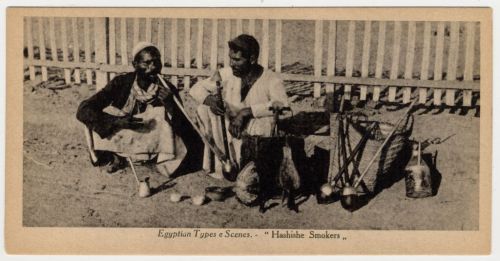

The first known record of hashish consumption in the Middle East occurred around 900 CE. Over time, as other empires came through, conquered, and absorbed cultural elements from populations in southwestern Asia, hashish became included in an inventory of exotic trade goods and was taken back to empires’ capitals. In the thirteenth century, Genghis Khan spread the use of hashish across the Asian continent. Sheikh Haydar, a Sufi monk living in Safavid Persia in the fifteenth century, recorded an account of ingesting cannabis resin directly. Hashish made its way to Europe in the nineteenth century, when Napoleon introduced it to the French after his army’s campaign in Egypt and Syria.

in contemporary mizrahi contexts

Following the spread of hashish to the Maghreb, Morocco eventually became one of the biggest exporters of this substance. Its commonplace use across North Africa, where hashish smoking remains prevalent today, can arguably be attributed to a historical relationship between the land’s Amazigh and Jewish inhabitants.

Dr. Doron Danino, an expert on Moroccan Jewry, expanded upon this interesting connection in an interview published in the Times of Israel. In reference to the nature of Moroccan society in the seventeenth century, Danino explained,

“The Jews, in general, did not grow cannabis, […] But they received a monopoly from the king for the sale of tobacco in Morocco, and that included sales of the cannabis plant and the hashish produced from it.”

Because the rural Amazigh farmers who grew cannabis often did not speak Arabic, a pragmatic partnership developed between these cultivators and Jewish merchants, who acted as middlemen in urban trade deals. According to Danino, “Jews used to speak several languages, and they had a business sense, which made it a mutually beneficial partnership.”

Apart from their role in selling hashish, it remains unclear whether or not the recreational use of cannabis was common among Moroccan Jews. However, further inspection of Jewish texts can reveal possible connections between hashish, biblical Jewish lore, and ritual practice.

in jewish texts and ritual observance

The use of hashish and cannabis in Jewish tradition is controversial, to say the least. The Tanakh includes numerous mentions of a grain or spice called qaneh-bosem (קְנֵה-בֹשֶׂם). In the Book of Exodus, G-d instructs Moses to carry this plant with him as part of a spice collection for anointing ritual sites, deeming it too holy for use by laymen (Exodus 30:22-33).

Most translations describe qaneh-bosem as “sweet cane,” which is, at most, a vague estimation of a proper translation, since no specific plant has been definitively attributed to this Aramaic word. The identity of qaneh-bosem is widely disputed- but some researchers and users of cannabis contend this mystery spice could be cannabis. It is described as an “aromatic grass” (which is exactly what I would call cannabis) that came from distant lands, most likely being northeastern India. The plant is noted to grow between three to five feet tall (*ahem ahem), growing in marshy areas (Jeremiah 6:20).

Obstacles in identifying biblical plants are also indebted to the Torah’s early standing as a completely oral tradition for many years, which can, of course, lead to some mistranslations. In his book The Living Torah (1981), Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan proposes that the translation of qaneh-bosem as “cane plant” is, in fact, incorrect, having resulted from a misattribution to the Egyptian word kalabos– a cane that grew on the Nile.

Jewish utilizations of hemp are also mentioned in medieval rabbinic texts and more contemporary records of Jewish religious practice. Yosef Glassman, a geriatrician living in Boston, has extensively researched the use of cannabis in Shabbat rituals. He cites the Talmud as a record of Jewish people using hemp to make textiles for tallitot and tzitzit. Separately, Ashkenazi rabbinic authorities characterize cannabis as kitniyot during Passover, so smoking hashish or eating hemp seeds (which have no psychoactive effect) during the grain and rice-free week would be heavily frowned upon. Still, there is no refuting that Hashem did say, “Behold, I have given you every herb yielding seed, which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed—to you it shall be for food. (Genesis 1:29)”

In 450 BCE, Herodotus wrote in Histories that Persians discussed diplomatic policies while drunk, then rehashed while sober (or vice versa) to see if they still held fast to their earlier claims. Similarly, a cornerstone of Jewish identity is a fierce love of argument and discussion- coupled with intoxication, of course. At least that’s what I saw that one time at Chabad. But I guess now we have proof that it wasn’t the first time Jews have taken things a step further than wine.

Additional writing and illustration by Sophie Levy and Evan Mateen.