My first encounter with a hyper-masculine Israeli man was on my Birthright trip in the summer of 2017. He was a soldier – stout, muscular, uniformed – paired with my group as a part of mifgash for the whole 10 days we were there, and a few days into the trip he decided he would sit in the empty seat beside me on the bus. I was unsure about him— he was brash in the way he spoke to me, sat very close, and asked me incredibly intrusive questions about my family and dating history. At one point, he even put his hand on my bare leg as we spoke.

A very different person at that point in my life than I am now, I didn’t know how to handle the situation. I didn’t want his hand there, but I was warned that Israeli men may come on strong, and that’s just the way they were. Plus, every fellow cis-het woman on the trip thought he was cute, so maybe I should just let him keep his hand there until he got bored.

A few days later, this man had conducted similar flirtations with all of the other female students on our trip. Then, he forced one of my friends into a broom closet with him despite her saying no. I don’t know the details of what happened inside or if she decided to tell staff; what I do remember, however, was that she was understandably shaken. When she told a group of us what had happened, we were uncomfortable, though I regret that we weren’t more disturbed. I think had this incident happened with a non-Israeli, we would have been more supportive of our friend. As it was, we chalked up what happened to “cultural differences.”

We had heard this idea expressed by Birthright staff, who had told us that soldiers might behave this way. When I told a staff member that the particular soldier on my trip was making me feel uncomfortable and was creeping a lot of us out, I received something to the effect of “Yeah I know, he’s just Israeli” in response.

A spokesperson from Birthright Israel told New Voices, “We have a zero-tolerance policy for sexual misconduct. We have a strict code of conduct for all participants and staff that encourages participants to notify us about any concerns so that we may address them promptly.”

_______________________

I haven’t been in Israel for 3 years, so I can only assume if I returned I would be greeted by the same spectrum of sometimes-welcomed flirting to uncomfortable, charged encounters. Misogyny in the Israeli male population is deeply-rooted, and it doesn’t come out of nowhere.

After the Holocaust and the founding of the State of Israel, shame surrounding Jewish men’s masculinity became a driving force of the Zionist movement. As Karin Carmit Yefet, a Law Professor at the University of Haifa, notes in her Feminism and Hyper-Masculinity in Israel: A Case Study in Deconstructing Legal Fatherhood, masculinity is often constructed and performed in response to marginalization. “The process of redefining hegemonic masculinity undertaken by [Jewish men] may take the form of hyper-masculine gender performances such as demonstrations of sexuality and power,” she writes.

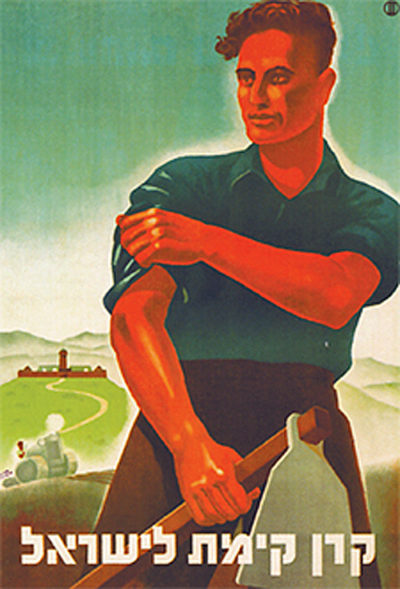

Redefinition and reassertion of such masculinity took many forms. Looking at artists’ depictions of Israeli Jewish men in the newly-founded State, a clear message comes across: Zionism has created the possibility for the “New Jew,” one who is strong, independent, and – freed from Diasporic oppression – finally masculine.

Until recently, I wasn’t aware of all the complexities within my encounter with the Israeli soldier. It wasn’t until I read Nylah Burton’s “The Danger of Calling a Jewish Man a ‘Nice Jewish Boy’” in Alma that I realized toxic masculine behavior in Jewish men could be taken seriously, instead of given a pass. Burton writes about a date with a self-declared “Nice Jewish Boy” (NJB), and how “his attempt to benefit from the stereotype of the NJB made me realize that the stereotype itself is not only harmful, but it impacts the way Jewish women experience sexual harassment and assault.” Her words rang true to me, even when “NJB” was replaced with “Israeli.”

In American circles, it has become commonplace to see the Israeli man as almost the opposite of the NJB; instead, he is a hyper-sexual bad boy whose allure is irresistible. Underlying the Israeli man’s supposed sexual appeal is the concept of Jewish Survivalism, which encourages Jewish men and women to marry and reproduce in order to ensure the continued existence of the Jewish People. This schema excuses inappropriate behavior towards women, especially when the perpetrator is an “attractive” Israeli man. Why? Because some think these men making advances on Jewish women facilitates the survival of the tribe.

Even one of the founders of Birthright, Yossi Beilin, shamelessly names a goal of the trip as “creating a situation whereby spouses are readily available,” as Sarah Seltzer reports in “Birthright Israel and #MeToo,” published in Jewish Currents. And these spouses aren’t just any Jewish men – they are Israelis, whose proximity to the IDF and distance from the Diaspora are supposed to make them seem both masculine and exotic. Of course, this framework dehumanizes both Israeli men and Jewish women, who become nothing more than vessels for childbearing. Seltzer writes about a woman who was raped by one of her mifgash soldiers on Birthright, and who feels that “the combination of hook-up pressure, spring-break partying, and romanticization of planned encounters between Israeli soldiers and American women” on the trip made her assault feel “fated.”

Speaking personally again, I am a student leader at the university level and have come into contact with Israelis and Israeli-Americans through multiple Jewish community events. There is one Israeli student in particular who I work with closely, and he has continually made me uncomfortable with his constant suggestive and long stares at my body and in his physical and verbal intrusion of my personal space. Past staff members of campus Jewish organizations have brushed off his behavior and chalked it up to his “culture” when I brought up my concern, though one did just tell me to tell him to F off. Similarly, on my Birthright Israel trip, the inappropriate actions of the soldier were dismissed. I know that students have been banned from my organization for sexual harassment, but where is the right place to draw the line? At what point does this performative masculinity become abusive?

On my campus and on the national level, Birthright and other trips to Israel are often advertised with promotional materials detailing the allure of hot Israeli soldiers, hook-ups, and relationships. While finding love on Birthright is certainly not a negative thing, we as a community need to examine the underlying assumptions that excuse sexual violence in the name of continuity. I worry that the more we continue to objectify Israeli men as a community, the more we endorse a sole (and dangerous) masculinity as a standard for Israeli men. The consequences are severe: we make it harder to both recognize inappropriate behavior towards women and hold those responsible accountable as human beings.

Carolyn Brodie (she/her) is a senior at the University of Pittsburgh where she is pursuing a double major in Psychology and Africana Studies and serves as the President of the Hillel Jewish Student Union. Social justice, equity, cultural competency, and tolerance are all topics that interest her, and she has been told that the way she talks about these topics makes her sound like she is pushing a liberal, feminist agenda. She takes this as a compliment. Follow her on Twitter: @ceeebrodie.

Featured image credit: Flickr.com/Israel Defense Forces.