It was on the plane to Warsaw that Irena Klepfisz’s writing began to feel less like poetry and more like prophecy. As I stared out the window into the hazy clouds, my fingers traced the words on my worn copy of Klepfisz’s A Few Words in the Mother Tongue. She looks out the window. All is present. The shadows of the past fall elsewhere. I repeated these words in my head as the plane touched down. All is present. It was easier than thinking about the obvious—how I was the first person to go back to Eastern Europe since my family left the Pale of Settlement in poverty, fleeing from pogroms. What did it mean that I was returning to a place that had been so dangerous that my ancestors had to leave? How would they feel about me going back? I didn’t know. The shadows of the past fall elsewhere.

As I boarded the bus to the hotel, I took stock of my surroundings. First of all, my group. Eighteen Columbia and Barnard students: a fortuitous number in Judaism. 18 represents life (חי); a good sign. Two very dedicated Hillel staff members, another good sign. On the itinerary: three cities – Warsaw, Lublin, and Krakow – a day trip to a small town called Checiny, and two Shabbats.

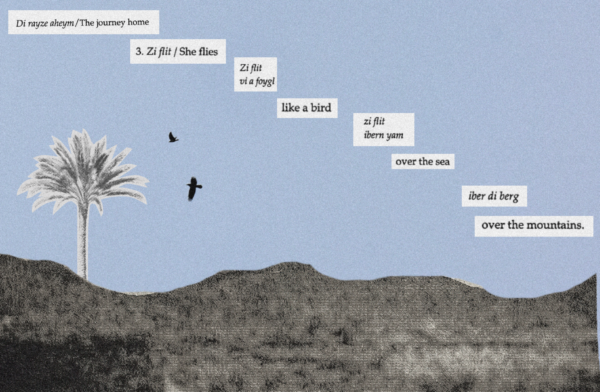

The trip was carefully planned to take us through 2,000 years of Jewish history. We were to explore the thriving Jewish life that existed for centuries before the Holocaust, and was now being rebuilt. I was grateful to be on a trip that was entirely in Poland and would not conclude in Israel, like March of the Living or other similar programs I had heard of. To go from the gas chambers to the clubs of Tel Aviv in less than a month felt like an incomplete picture of Jewish history, in which Poland and its concentration camps is the ultimate site of destruction, and Israel is the ultimate site of revival. In this narrative, Yiddish language and culture is to be cast aside and scorned, and the Polish Jewish communities of today are erased. I did not want to cast aside and scorn my ancestral history in the name of Jewish nationalism. I wanted to uncover it, hold it up into the light, and see the beauty and the adversity of Jewish memory. So, along with my eighteen classmates and two Hillel professionals, I flew, like a bird, over the sea, over the mountains.

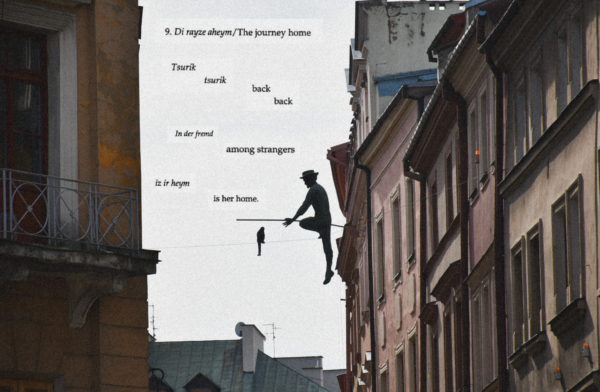

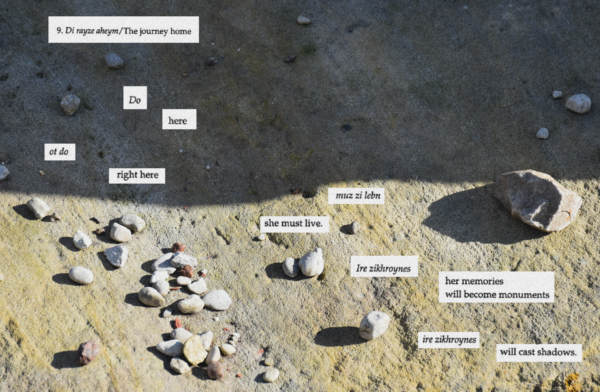

I first read Irena Klepfisz in 2021, as a Jewish Women’s Archive Rising Voices Fellow. I was writing a blog post about feeling rootless amidst a lack of knowledge about my familial history. When I described how unmoored I felt, my mentor, Sarah, sent me a poem in Yiddish and English called “Di rayze aheym / The journey home” by Irena Klepfisz. In der fremd, iz ir heym, it said. Among strangers is her home.

Reading this first poem was a near-biblical revelation. Never until now had I felt like my confusion over where I belonged could be articulated. Yet, here it was on the page. In der fremd, iz ir heym. The more I learned about Klepfisz, the more I was able to reconcile different parts of my identity with my Judaism. I read her poetry about queerness, and considered my own sexuality and how I wanted to label myself. I read her poetry about Bundism, and considered my relationship to socialist ideals. I read her poetry about anti-Zionism, and considered my own relationship to Israel and the plight of Palestinians. I read her bilingual poetry in both Yiddish and English, and realized I wanted to study Yiddish culture in college. Klepfisz’s poems are multifaceted – they are not merely Jewish, queer, or socialist. They are all of these things and more.

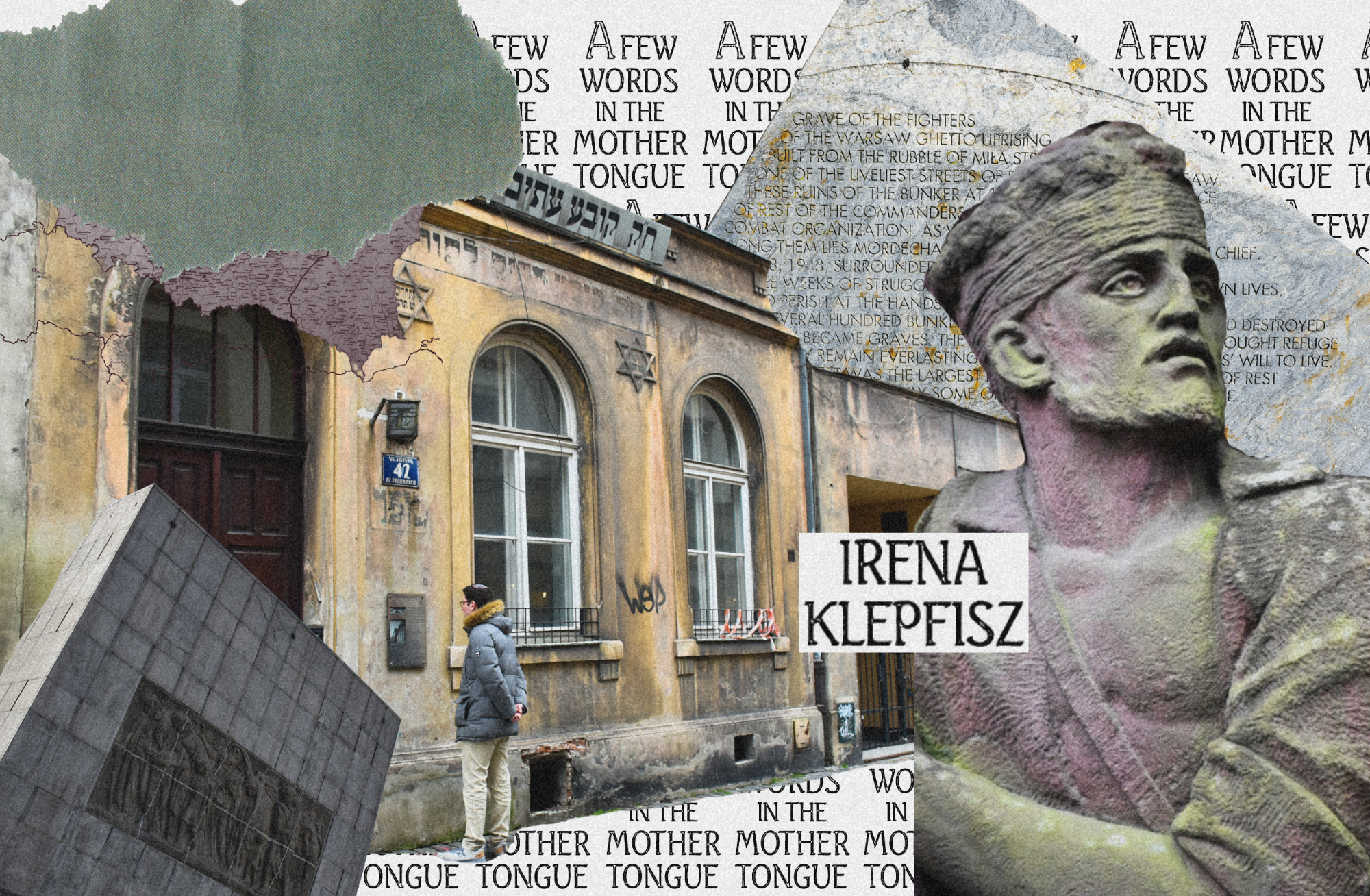

Klepfisz is a Jewish poet who was born in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1941. Much of her poetry is about surviving the Holocaust in Poland, her Bundist parents, and her return to Poland in 1983 for the 40th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. When I put A Few Words in the Mother Tongue in my suitcase, I hoped that it would serve as a road map for my journey through Poland.

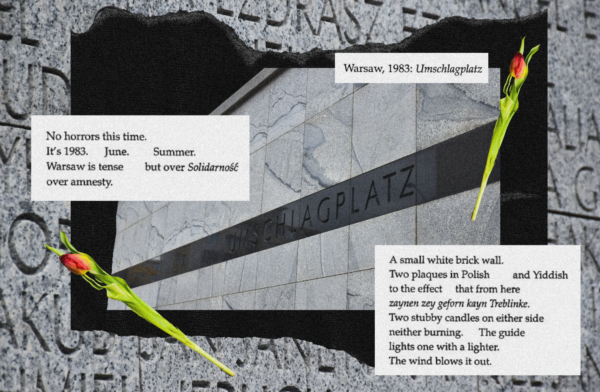

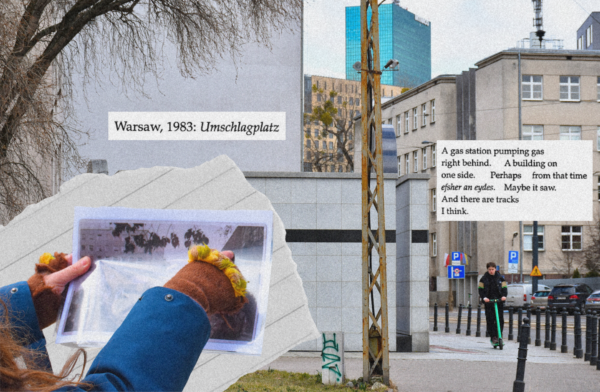

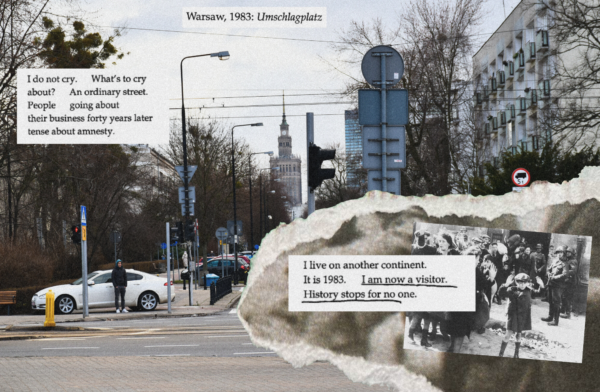

Irena Klepfisz wrote “Warsaw, 1983: Umschlagplatz” forty years before I found myself standing in her footsteps at the Umschlagplatz Monument. Hebrew, Yiddish, Polish, and Hebrew carved into cold gray stone. An unlit memorial candle and three wilting flowers. I felt profoundly sad. Was this enough? What could ever be enough? The wind blows it out.

“This was the loading depot where over 300,000 Jews were sent from the ghetto to Treblinka and other camps,” said our guide. I stared at the shoe store across the street. A man on an electric scooter went by. Our guide pointed at a nondescript office building down the street and held up a laminated photograph. “This was where the SS oversaw Umschlagplatz operations from.” Maybe it saw, I think. A woman ran past us in jogging pants.

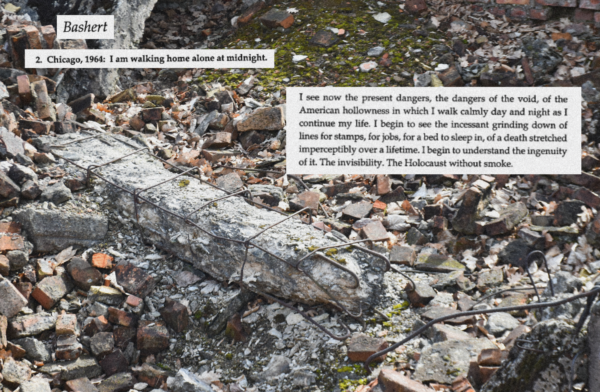

At first, I remember feeling angry. Why is there a shoe store here? How are people going for runs here? As we walked down the street towards the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto, I tried to remind myself that this was an ordinary street, with ordinary people. History stops for no one, writes Klepfisz. Indeed, history did not end in 1945. Who was I to judge these people living their lives? These buildings for existing on top of old ones? On top of ashes? History stops for no one.

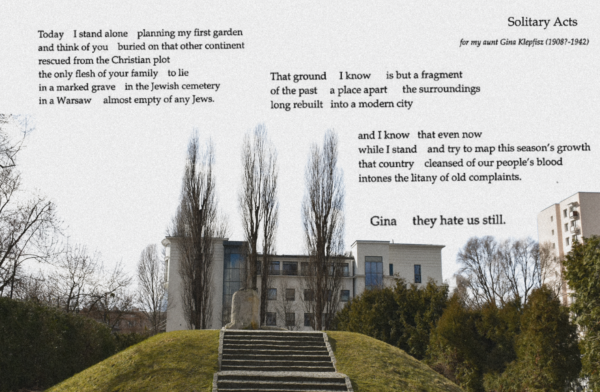

The Anielewicz Bunker at Mila 18, the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, was surrounded by beautiful white residential buildings. As I placed a stone on the memorial, I looked up at the hundreds of balconies surrounding us. Could the people who lived there see me? Did they see Jews come every day, putting rocks on graves, commemorating the deaths, lamenting the past? When they sat on their balconies on nice days, could they see the memorial? Did they know what had happened?

All of Warsaw felt like this. This shopping mall is on top of where a huge synagogue once was. This apartment building was built out of the rubble of the old Warsaw ghetto. I never got used to it.

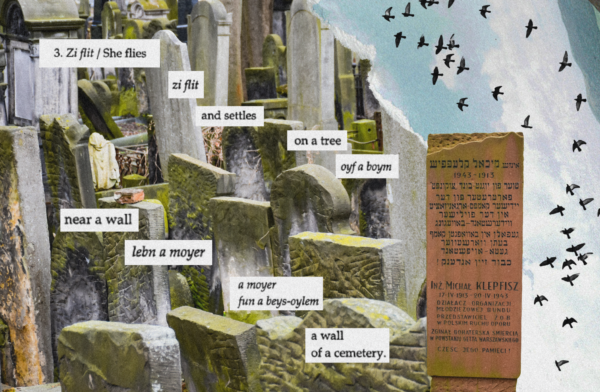

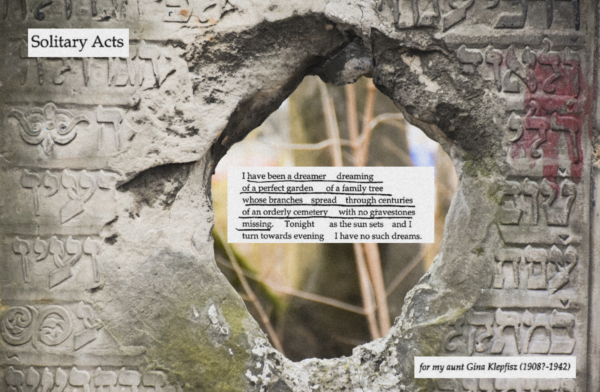

Going to the old Jewish cemeteries was one of my favorite parts of the trip. It sounds strange, but they were some of the most beautiful places I’d ever seen in my life. A guest speaker explained to us before we left for Poland that cemeteries were a sign of how much Jews thrived in Poland for centuries. “They wouldn’t have created cemeteries in a place they thought they were going to have to leave,” he said. “Cemeteries mean people plan on staying there for a long time.”

In Warsaw, I saw the grave of Irena Klepfisz’s father, Michał Klepfisz. In Lublin, I saw hundreds of Hasidic Jews crowd around the grave of the Seer of Lublin in a cemetery founded in 1541. In Krakow, I saw a wall made out of broken gravestones. I placed stones on as many graves as I could.

Poland has a long history of Holocaust denial and distortion, and many Polish people we met insisted that Poland was occupied and not the occupier, here to build German camps on Polish soil. But what about after the war was over, when Jews returned to their towns only to be killed by their Polish neighbors? What about the pogroms in Jedwabne, Radziłów, Szczuczyn and Wąsosz?

These examples of fervent European nationalism can feel far away in both time and place for American Jews like myself. Yet Hitler himself was inspired by the enslavement of African Americans, the annihilation of Native American communities, Jim Crow laws, and the ultra-restrictive Immigration Act of 1924. Nationalism is contagious.

At Auschwitz, I thought about how many of my peers see the camps and think only of the need for a Jewish national homeland. But quietly, I wonder if they’ve considered that fervent nationalism provided fertile ground for the hatred of Jews to flourish. Looking back at Jewish history, I find myself wary of the worship of a state, of the idea that somehow a nation would save us.

As our bus drove through the countryside, I stared out at the rolling fields and tiny towns and waited for some kind of deep-rooted generational knowledge to alert me of where my ancestors once lived. I imagined how it would feel to have a complete list of family members, where they came from in Europe, what their lives were like, if they kept Shabbat, what they left behind when they came to America. Were there midwives? Folk healers? Peddlers? Revolutionaries? It has always felt like my family tree is full of blanks, and every time I try and fill them in, my efforts are thwarted by the vastness of time. It was too long ago, too far away. There are no more answers to be found.

In Poland, I didn’t know exactly where my family would have lived. So, everywhere we went, I imagined that they had been there. They could have been here, I thought in Warsaw. They could have been here, I thought in Krakow.

Irena Klepfisz taught me that there is more to my Jewish life than I ever could have imagined. While my Poland trip was over a year ago, I think about it all the time. And I cannot think about my time in Poland without thinking of her poetry.

The moments I remember the most clearly from Warsaw, Lublin, and Krakow form a patchwork of darkness and light. I remember ornate synagogues, misty cemeteries, long bus rides with my friends, singing songs on Shabbat, the boundless joy of Purim, and many, many pierogies. But I also remember the rubble of the Warsaw ghetto, brightly colored Lublin homes built on the basements of Jewish apartments, building after building and city after city that used to be full of Jews and is still rebuilding 80 years later. Her memories will become monuments will cast shadows.

On the plane home, I contemplated how the way I thought about New York as a thriving center of diverse Jewish life is how Jews my age thought about Warsaw for centuries. I understand the instinct of so many Jews to say, “no place is safe for us, not forever.” Yet, the poetry of Irena Klepfisz has shown me to fight for the continuation of multiculturalism that allowed Jews to thrive in Poland until nationalism overcame it. Right here she must live. Right here, I must live, dreaming of Jewish futures informed by Jewish pasts.