From fashion to music to culture, a conversation between popular past and contemporary Jewish masculinities

It was 1976, and producer Phil Spector was waving a bottle of Manischewitz in one hand — in the other, a gun — in the face of Leonard Cohen. The two were working together on Cohen’s album-after-marriage, Death of a Ladies’ Man, where the colloquial married man, Cohen — a dictator of suavity — was destined to die. Unbridled Jewish manhood was in the making, and it was angry. Today, it rages on.

Could secular Jewish men find meaning in manhood? As the Old World was forgotten in the early 20th century, the submissive nebbish, a man of depleted confidence, was soon to be pitted against what I call “the Lion,” the ferocious figurehead of Zion: the muscularized Israeli with his sleeves rolled up, buttons unfurled at the chest, ready to pave through kibbutzim and to outshine the nebbish with his confidence. Where the nebbish was portrayed as neurotic, destined to die — weaving himself meekly around the dilemmas of survival in Europe — the Lion (or “sabra” man) would be compelled to charge forth. As the Jewish state was born, the Lion would supposedly redeem European Jewry with conquest as an iconoclastic laborer. And today, the Nice Jewish Boy (NJB) coddles the Anglophone Jewish world as a charmer, a bachelor, but most ultimately a young man.

Conceptions of Jewish manhood throughout history have manifested as a collective response to antisemitism and, often, assimilation. The “Jewish man” was not so much a result of one’s grappling with personal identity as it was a rendering of pain, reaction, and transmutation of his own belittled existence.

But over the last 100 or so years, one thing can be certain: the remaking of the young Jewish man has been unconscionably sexy. You can imagine him today: a form-fitting tank top (sometimes denoted a “wife pleaser”), fielding tresses of chest hair. Wrangler Wrancher dress jeans or vintage Levi’s denim hugging his long legs. A gleaming Star of David necklace, dipping low, to remind you that he’s power. A mustache, or a beard, but dark hair. He is Ashkenazi, maybe ancestral. He is daddy. He is Americana, and he is folk, and he is fit. And these are things he owns and reclaims.

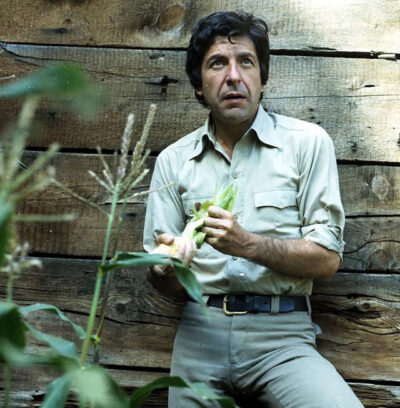

Leonard Cohen was the Jewish man, the debonair romantic, his pearl-snapped Western flannel tucked beneath his snug trousers. He even became the agricultural agitprop Israel wanted him to be, seen shucking corn with his bare hands (Exhibit A). When he wasn’t waffling about his love for a woman, he was being hot and sophisticated.

Exhibit A (Photo credit: John Rowlands, 1974)

Since the COVID-19 pandemic implored us to crawl within ourselves, male Jewish influencers have sublimated their fashion, and their faith, into these brute masculine aesthetics alongside the sensual Jewish crooners of Cohen and other bygone folkish Jew-men: the Byronic Bob Dylan, Jim Croce (Jewish-by-marriage), the hymnal Woody Guthrie (wed to Khane “Marjorie” Greenblatt, the daughter of Yiddish poet Aliza), or Paul Newman. These Instagram guys have developed their own online personas, too: Albert Muzquiz (@edgyalbert), Yung Chomsky (@yungchomsky), and Gabriel Mor (@gabriel_mor).

As I interpret, the shift beyond COVID has been a marked exploration of the self and gender expression. These influencers are hairy, aspiring Philip Roth protagonists, and they are declaring a new world order right before our eyes. They have found comfort in the masculinized body as home, putting form-fitting clothes of a certain declaration of Americana — or Zion — on the shapely body parts that declare the Jewish man, like other men, a sexual being. The wardrobes of the bygone Jews, like Cohen, are being referenced and revitalized from no more than half a century ago. At the same time, the nature of social media influencer culture makes this clothes-wearing feel more strained — as if these performances of masculinity are showing the world how to represent the contemporary experience of Jewish manhood.

Clockwise: The Instagram accounts of Albert Muzquiz, Yung Chomsky, and Gabriel Mor.

This isn’t totally a Jewish phenomenon. Men and mascs across America, of all backgrounds, are dressing like contemporary cowboys at the crossroads of smutty gentlemen. Muzquiz, from Los Angeles in the throes of Southern California, is an exemplary case of true Western wear finding historical meaning in the temperate Western United States. While Phil Spector more proudly waved Manischewitz all those years ago, Muzquiz and today’s Jewish man are plodding around with 6-packs of Modelo. The land is a main character in their aesthetic — whether Zion, or the ditzy Western Americana that even Lana Del Rey tried to warn us of.

And with the land as a central figure, unsurprisingly, comes a bad case of Ashkenormativity. Why must all of these men — from Cohen to Muzquiz — be Ashkenazi to be loved? Maybe it’s because the Ashkenazi imaginary, Yiddishland, is more readily a tangible creation. The land of Sepharad and Mizrah are not depicted, yet, as masculine imaginaries — as if their diasporic histories were swallowed, regurgitated, and cast about confused. The reverberating call to Israel, the most “masculine land” of the Zion Lions, doesn’t remedy this notion, either.

I’m from New Jersey, born and raised, but I, too, have been called to Yiddishland, a place that doesn’t neatly exist. Yiddishland, the folkish home of the Ashkenaz, seems much more to be a cultural idea than a physical location, often represented by its in-community while staking claim in the rich traditions of the diaspora. And as my adulthood beckons me, these Jewish influencers are catapulting me forward to embrace this folk-derived land, the spirit of America or Yiddishland at my thumbs. My “downright sinful” ‘70s Angels Flight bell-bottoms sit in my closet, beside my ‘60s Acme biker boots weathered with time. I own genuine leather garments from factories that Oklahoma will never see again. For a folkish home or concept to exist — much like that of the land and the ephemeral vintage garment — a physicality must be lost to time.

I’m also queer, with an eye for the reclamation of masculine clothes by men, in the idea of externally performing a queer identity. My queer friends and I joke that this overlap — the reclamation — also pervades in womenswear, where traditionally feminine garments are worn as a performance of queer fem(me) identity. For the man, these Jewish influencers seem to invoke a gender performance that amplifies their cisgender maleness, so much so that it feels queer or, at the very least, verging into its territory.

From the übermasculine portrayals of men in Tom of Finland’s art to the ‘70s Castro clone, the archetypal queer man is, foremost, a masculinized entity. While Muzquiz did perform in theater productions with the rest of his Vassar College classmates, his image does not allow him to be decidedly queer. But there’s something to be said about the homo-heritage of clothes and the men that have worn them. In general, performing as a soft queer man — rooted in the fashionable externalization of historical masculinity — feels only right. While the convergence of this NJD aesthetic and queerness does not manifest explicitly in these influencers and their personal approaches to clothing, the connection deserves more proper investigation.

Muzquiz et al. have no children, but even in their relative youth have they transcended NJB status, almost ascending to the status of “New Jewish Daddy.” If a 28-year-old man can cosplay as a rugged 40-year-old man in workwear to perform as a flirt, he will find a way. As the world will tell us, the Jewish are tenacious. Their thirst traps can’t be stopped.

There’s something so acerbic about the state of “the outfit” because whatever constitutes one is always up for debate. I can remember last Passover when my cousin told our grandfather he had on a cool outfit, to which he snapped: “This is an outfit?” Needless to say, he moved on with his life. But my grandfather wears flannels, tucked into pleated trousers. A sturdy belt with an angular buckle. To him — what the NJD is proclaiming as an artful garb — is normal. It’s what a man wears. There’s no thought to the putting-it-together that seems so endemic to the Jewish man of now.

Apart from hopping onto Instagram to post a virile picture, perhaps the most crafty thing about the NJD is wearing his clothes. He won’t be the name of a boygenius song. He won’t be the inspiration for a klezmer album. To look masculine and Jewish today is not a byproduct of stardom, as it once was, but the integral point of it. It’s not his job to be an object of talent. He will only be a hot man, reflecting one of the key aspects of those Jewish singers and icons of the last century.

When I visited Jim Croce’s grave in Malvern, Pennsylvania’s Haym Salomon Memorial Park — due west of Philadelphia where I go to school — I wore all the things: decommissioned U.S. Navy seafarer jeans, a Western sherpa-lined suede vest, and my velour-lined shirt from h.i.s., a brand that prophesied that any “dude” could turn into a “stud.”

That same day, I drank the Pennsylvania-born Yuengling in a pizzeria. “Yuengling,” however ironically, translates from German as “youngling” — a boy who is not yet a man. Leonard Cohen wasn’t there for me to wave that in his face, but I suppose, for me, some things are closer to my heart and my home. I can’t argue with that. Jim Croce once sang to the world: “Yeah, I used to be a fighter but / Now I am a wiser man.”

I try to be a man so badly, but I must be Jewish, too. These are things I’m coming to own, but not by my own invention. I, among many, am self-conscious about the pervading aesthetics of the man and how manhood’s aesthetics must be performed to be good.

It seems that to be a man — a Jewish one — is to be spun around by the generations of men that have made you and the worlds that made them.