Kessim on Sigd, clad in white clerical turbans and robes, embroidered, colorful umbrellas to announce and denote their presence, and wearing beautifully embroidered velvet cloaks. – Jerusalem, Nov. 23, 2022. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

Within many Black communities, migration often entails redefining one’s identity for the sake of others – shedding part of the self for the safety and comfort of a new identity. But in the case of Ethiopian Jews, “we’ve seen the opposite,” says Kes Shimon Semai Elias, an Ethiopian Israeli religious leader. “The younger generation is returning to its roots, studying, making demands. They want to know, to be connected.”

Ethiopian Jews are one of the largest Jewish demographics of sub-Saharan African origin, and the community holds great weight over conceptualizations of the Jewish and Black identity. While I’m not an Ethiopian Jew, their story has informed my understanding of my own Jewish and Black identity. The question of how to navigate both of these identities in a way that doesn’t diminish their significance is asked by many, regardless of where they live.

But the unparalleled mass migration of Ethiopian Jews out of Ethiopia posited this question to an entire community, not as a thought in the back of one’s head, but as an urgent issue only answerable by practice. It is an intergenerational question that is still receiving an intergenerational response.

Mythologization

From 1974 to 1991, Ethiopia found itself embroiled in a civil war, with the entire Horn of Africa caught in the political embers of the Cold War. Its government, the Derg, imposed policies that ignited tensions amongst Ethiopia’s diverse groups – tensions which, despite the government’s end, continue to this day. But the origin of many of these tensions date back well before Ethiopia’s civil war.

The relationship between Ethiopian gentiles and Jews has significantly defined the region’s political, mythic, and religious identity throughout the long period of Jewish presence there. The origin of this Jewish community is somewhat contested. They prefer to be known as Beta Israel – Ge’ez for “House of Israel”, reclaiming the term from the historically pejorative term “Falasha”, meaning “stranger” or “exile”. The conflict is exemplified in the Ethiopian national epic, “Kebra Nagast (Glory of Kings),” which stands as but one demonstration of the intangibility of Ethiopian Jewry to the identity of the entire state.

Mythologization acts as a tool the Ethiopian Jewish community can use to define itself, though it’s often used by those outside the community. Minorities that intersect Black and Jewish identity are often disarmed of the ability to define themselves due to having to reflect expectations as a part of the “Jewish collective”. This forces the “Jewish validity” of communities like the Beta Israel to be evaluated on different conditions than other groups considered already in the “mainstream“. I understand this feeling from firsthand experience. This is why I’ve been so intrigued by how it manifests in Beta Israel’s sense of self as one of the most visible Black and Jewish collectives.

More than one group has a pencil for the Book of Life.

The Haymanot

Because of the sparse correspondence with the greater Jewish world until the 19th century, the origin of Beta Israel has become mythologized. That relative isolation – which many oral and written histories date to the 15th century – led to a unique way of practicing Judaism known as the Haymanot (“faith” in Amharic). This isolation allowed the most contentious aspect of their religious identity – the absence of a rabbinical polity – to anchor itself. With this in mind, some assume that Jewish law or Halakha was completely foreign to the Haymanot – which is false.

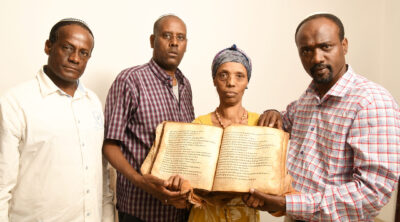

Traditionally, the custodians of the Haymanot were the Kessoch or Kahenim, (plural for Kes or Kahen). These are priests trained in reading the Orit, a series of eight holy books, combining the Torah alongside Joshua, Judges, and Ruth, and doing so in Ge’ez, a liturgical language shared by both Ethiopian Orthodox Christians and Beta Israel. While Hebrew and Aramaic are in the same linguistic family as Ge’ez, the usage of Hebrew in Beta Israel liturgy is only a recent development – consequential to the mass migration to Israel. Even so, and also while lacking the context that lead to the introduction of Siddurim in Rabbinical Judaism, similar liturgies like The Sacred Song existed amongst the Beta Israel long before mass-migration.

This, among many other aspects, illustrate Beta Israel practice as uniquely Ethiopian as it is uniquely, and undisputedly Jewish.

The kessim, for instance, are seen as manifesting a similar spiritual authority as those of the priestly class during the existence of the Temple in Jerusalem. As such, they bear special rituals in traditional spaces, such as delivering the Birkat Kohanim (Priestly Blessing) as is done by many Rabbis and traditional Cohanim. These priests practiced the rabbinical role of being adjudicators for legal inquiries, but, lacking the Talmud, utilized orally-transferred Torah, mirroring elements of Rabbinicalism. The preservation of this oral tradition was the task of the debtera, a clerical role shared with other Ethiopian faiths, combining the religious role of a cantor with the troubadour – or bard-like lay role of the azmari – a Horn African equivalent to the griot of West Africa, sharing, “documenting”, and acting out fables, lessons, and more. The preservation of oral torah found itself uniquely adapted to African traditions of oral transmission, and saw with it, a Halakha in many ways as vividly complex as that of Rabbinical Judaism.

Migration & Relocation

These traditions and the role of Beta Israel’s religious polity evolved over time, often through interaction with non-Jewish Ethiopians. Safety, or lack thereof, was generally defined by the attitude of the Ethiopian state to Jewish presence rather than animosity of the gentile population. The complexity of this relationship continued to the era of the Derg, who saw many Ethiopian Jews amongst its early supporters, often prompted by opposition to the former monarchy’s anti-Jewish policies. Unfortunately, as with all civil wars, the period saw immense displacement, loss of life, opportunistic shifts in allegiances and intents, and in Ethiopia’s case, a near-existential threat to Jewish welfare in the Horn. This prompted the mass migration of the community’s thousands of members north into Sudan, itself undergoing its own political turmoil. It is at this point that Kes Semai Elias remarks:

“When we got to Sudan, there were 35,000 refugees. We didn’t know anything, nothing about Aliyah. We prayed to God for a miracle. After eight months, we ran into a Red Cross worker who knew the Israeli workers. The Israeli had the Mossad in Sudan and we met through them the right connections…The Mossad put in an airfield, and at night they would send (an) army craft to us for (a) flight. So they landed the Hercules transport and we flew to Israel.”

The Israeli government controversially organized Operation Moses, responsible for Kes Elias’ transport and the gradual relocation of most of the community through a series of airlifts. Leaving behind 1000 in Ethiopia, with 500 of those 1000 being airlifted by the US at a later date. Some 4000 died on their path to safety. This experience, for a majority of its participants, would be their first exposure to living in the “mainstream” Jewish world. Adapting to the social demands of that environment was a reality whose effect has been overlooked.

“Struggling for a place in this society”

The immense trauma from the migration redefined what it meant to be an Ethiopian Jew, from being Jewish in the face of a gentile environment, to being Beta Israel in the face of a Jewishness that – for the first time – would be defined for, rather than by them. In a 1994 interview from the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, the activist Erez Kinde, then member of the Movement for Ethiopian Jews, remarked:

“We are still struggling for a place in this society, for the right to be married and divorced by any rabbi in Israel, for our religious leaders to be recognized, for decent housing and jobs. As far as I can tell, this is only the beginning.”

This first generation of integration was passively alienated, with the Israeli rabbinate approaching the community as having proximity to, but not expressing halakhic soundness. Many were obliged into converting to mainstream Orthodox Judaism – an expression of distrust that echoes a trend of rabbinical anti-blackness, wariness over the novelty of the community in the Israeli cultural milieu, and disdain for the Haymanot. Various rulings refused to see traditional Beta Israel clergy as legalistically authoritative, obliged Kessim to obtain rabbinical semicha, and barred the investment of new Kessim. This stance eventually subsided in 2018, but it highlighted the Israeli government’s pursuit of a homogeneity that went against what, to Beta Israel elders, defined Ethiopian Jewishness.

Between the airlifts and today, the second and third generations have established themselves and their identities in their new “Israeli-ness”, and with it, have redefined what it means to be Beta Israel. Ethiopian Jewish elder and Rabbi, Dr. Sharon Shalom, was aware of the pressure to integrate into mainstream Judaism. He compiled a series of halakhic responsa and guidance for introducing or whittling traditions as each generation comes forth. This book, From Sinai to Ethiopia, can be read from the eyes of a Torah scholar seeking to preserve and adapt Beta Israeli ways of life as a new manifestation of the Haymanot. It can also be read from the eyes of a community leader seeking to find his people’s place in the new environment. From both lenses, it is written knowing the Haymanot is in the hands of its youth.

L’dor V’dor Practice

Ethiopian Jewish integration into the mainstream left the Haymanot in the hands of the family. Like a spoken-at-home language, the way the children hold on to it varies depending on social environment, comfort, and knowledge. In the newer generations, youth often approach Kessim as community leaders more often than sources of religious guidance, but have not abandoned the religious aspects that that office embodies. According to Kes Semai Elias,that role has led to a rebound of interest in the traditions of the Haymanot, and in carrying forth its traditions. The most resounding example of the Haymanot’s refusal to wane is the prominence of the holiday Sigd. Sigd represents the community’s march to refuge in the Ethiopian Highlands in a time of existential threat. It is a very Jewish response, whose poignancy rings in the ears of Ethiopian Jewish youth to this day.

How these traditions manifest in future generations of Ethiopian Jews, may seem like slowly sinking ice in the tall drink of Judaism. We should know, however, those ice cubes – beautifully and stubbornly Jewish – will refuse to melt.