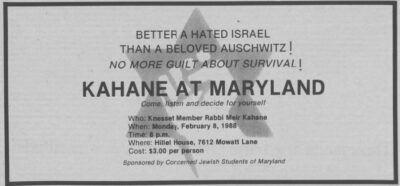

Meir Kahane delivers a speech to Maryland students in 1988. (UMD Digital Collections)

On November 5, 1990, just two weeks before he was slated to speak at University of Maryland, the ultranationalist rabbi Meir Kahane was fatally shot in a midtown Manhattan hotel.

The Brooklyn-born ideologue had relocated to Israel two decades before his assassination. In Israel, he founded the Kach party, which campaigned on the expulsion of Palestinian Arabs from areas under Israeli control. But Kahane still made frequent trips back to the US for speaking gigs on American college campuses.

As it turns out, Jewish students at the University of Maryland were quite receptive to Kahane’s ideas, even after his death.

Left without a speaker, the Jewish Student Union and Maryland Hillel joined forces to bring the closest thing to the deceased rabbi they could find: Kach International director Sol Margolis, who eulogized Kahane in front of over 200 students.

“I know that Rabbi Kahane is looking down from heaven with a smile, knowing that his message lives on,” said Jewish Student Union board member Brent Horwitz, who helped organize the event.

“His talks of Israel often brought tears to my eyes and fire to my heart,” wrote one Dubi Bernstein in the Mitzpeh opinion section. “He understood the Arabs best, and they certainly understood him.”

In Israel today, Kahane’s ideological successors are no longer at society’s fringes. Itamar Ben Gvir, one of his loudest supporters in government, is now at the helm of Israel’s police force, taking advantage of Hamas’s brutal terrorist attack on October 7 and the ensuing war to wreak havoc in the West Bank and beyond.

When a longtime Kahane disciple such as Ben Gvir remarks to Israeli media, as he did this summer, that his rights take precedence over those of Arabs, he is no longer saying it as a rabble rouser representing a “tiny minority” of Israelis, but as a government minister, forcing us to take the rabbi’s legacy seriously.

Now that he stands posthumously at the forefront of Israeli politics, a large section of the American Jewish media has begun to look back on Kahane’s decades-long career in the United States.

Although he is known in America for his involvement in the Soviet Jewry movement and local vigilantism, Kahane never concealed his reactionary agenda for Israel when giving speeches to UMD students. Evident from the abundance of news articles available in the university archive, Kahane amassed a substantial following on campus alongside hundreds of casual supporters, from the mid-1970s until the day of his death.

The far-right rabbi’s last visit to campus further embittered relations between Jewish and Arab students, leading to a tense state of affairs between the communities that lasts to this day.

Kahane made a name for himself in the US as founder of the militant Jewish Defense League, a vigilante group active throughout the 1960s and 70s on the streets of New York City. The group established patrols in the city’s Jewish neighborhoods, modeling much of its surface-level rhetoric and aesthetic after the Black Panthers, a group it often clashed with in the late 1960s.

Unlike the Panthers, the JDL went much further than just establishing neighborhood patrols, and was linked to a number of attempted bombing attacks on Soviet and Arab diplomats during its heyday.

Despite Kahane’s unending hostility towards mainstream Jewish organizations, which he regarded as part of an assimilationist, liberal American Jewish establishment aloof to issues of working-class Jews, university Hillel chapters across the country allowed him a platform time and time again.

If they didn’t sponsor him outright, as Maryland Hillel often did throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, they would simply cover their eyes while handing the rabbi a microphone.

“He was the outside speaker that was brought most frequently to Maryland by Jewish students,” Rabbi Bob Sacks, Maryland Hillel director from 1973-1991, recalled. Over the course of two decades, Kahane came to this campus at least eight times.

“Militant rabbi against racism”

Kahane made his first appearance at the University of Maryland in 1971 in the Stamp Student Union building, where he spoke to a 700-person crowd. Ahead of his debut visit, Kahane founded a campus JDL chapter as part of a larger push to popularize the organization among university students.

Over the next two decades, Kahane would return every few years to Maryland. He received little to no dissent from the student body, even when advocating to ban sexual relations between Jews and Arabs in Israel, or for the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from all territories under Israeli control.

Kahane also enjoyed sizable support from non-Jewish students in the 1970s. A few days after his first campus visit, then-SGA President Madison Jones was arrested along with Kahane and thirteen other UMD students at a JDL-organized protest near the Soviet embassy.

In the pages of The Diamondback and Mitzpeh student newspapers, Kahane was portrayed as a ragtag soldier in the fight against bigotry, rather than its adherent. The Diamondback’s published story documenting his 1976 visit described him as a “militant rabbi” who encouraged students to “fight racists,” while dancing around his statements and organized action against Palestinians, which he made no secret of.

In 1976, the rabbi gave a talk titled “There is No Palestine” while on a five-week trip to boost campus JDL membership. The same year, his fledgling Israeli group Kach distributed pamphlets in East Jerusalem urging tourists to boycott Arab businesses in the area.

Kahane returned in 1980 to give another speech, this time sponsored directly by Maryland Hillel. The summer of that year, he was arrested by Israeli authorities on the suspicion that he was planning attacks against Palestinian civilians in the occupied West Bank.

A dangerous concept

Kahane made his final and most controversial appearance at Maryland in 1988. His speech, “Better a Hated Israel than a Beloved Auschwitz,” attracted around 250 students, but brought hundreds of others to protests across the street from the Hillel building where he spoke.

Although this time his appearance wasn’t sponsored by Hillel directly, the organization’s staff still allowed him a venue.

“I was responding to two impulses, one is that Hillel should be open to controversial speakers, and the other is that the things he was saying ought to be protested,” Sacks said. Indeed, after introducing Kahane to students, he went outside to join the demonstration against him.

Inside the building, flyers named after Kahane’s recent book, “Uncomfortable Questions for Comfortable Jews,” were stacked on tables for curious attendees to take and flip through while waiting for the speech to begin. The flyer ripped into Israel’s Declaration of Independence, laying out the rabbi’s radical belief that Zionism and democracy are irreconcilable.

“Does the Declaration of Independence of Israel create a state of Jews or a state of schizophrenia?” it read.

Meanwhile, on the other side of Mowatt Lane, protesters amassed outside the business school into two fragmented groups. Liberal Jewish students and faculty affiliated with the ad hoc group Jews for Jewish Values protested separately from the Arab and Black students under the banner of the Organization of Arab Students (OAS).

“We felt that Kahane is not only a dangerous man, but a dangerous concept,” former OAS President Hakam Kanafani said. “This Kahane visit was an opportunity to show that we are also in a struggle against racism.”

During his stint as its president, Kanafani rapidly expanded the OAS, flipping the script on Kahane in the process and altering his public image among non-Jewish Maryland students from that of a militant with a supposedly noble cause to a far-right extremist bent on ethnic cleansing.

Members of the organization wrote frequent op-eds in The Diamondback furthering a new narrative about Kahanism. Former OAS member Elias Mansour derided the rabbi’s “sick ideas of institutional racism” and painted him in the context of global oppression at the climax of the divestment movement from South Africa.

Liberal Jews who protested that day found themselves in a tight spot — pulled between Jewish students attending Kahane’s event and the protesters who viewed his beliefs as a logical conclusion of Zionism.

After two months and back-and-forth between Jewish and Arab students in The Diamondback opinion section regarding Kahane’s visit, tension between the two groups came to a fore on campus during celebrations of Israel’s 40th independence day. In opposition to the event, Arab and Black students under the OAS and Black Student Union organized a joint protest against Israel’s military occupation and apartheid South Africa.

“When you talk about Palestinians, you talk about any of the oppressed people,” said Mansour to The Diamondback during the protest.

Especially now amidst the ongoing war, Jewish and Palestinian Maryland students may find this image familiar. Campus tensions between our two communities reached a boiling point in the aftermath of Kahane’s visit, but most of us are unaware he had a presence here at all.

Kahane biographer Shaul Magid believes that instances like these, collective amnesia about the far-right rabbi and his legacy, are the result of “a broader impulse to expunge him — and the radical militancy he represents — from our narratives about American Jewish culture and history.”

Kahane’s fall and rise

Although Kahane had become more controversial among the campus Jewish community by 1988, Mitzpeh’s coverage of his assassination in 1990 indicates that he was still popular. In an issue published a month after his death, the newspaper dedicated the entire international section to “Kahane’s Legacy,” featuring articles written by editorial staff.

Then editor-in-chief David Price penned a sentimental article under the headline: “Campus mourns rebel rabbi, legacy lives on,” which began with a quote from the president of Kach International praising Kahane for his ability to “inspire young Jews.”

While some non-Jewish students casually supported Kahane in the previous decade, this was not the case by the time of his death. The Diamondback ran one wire article on his assassination, and he soon faded from the paper’s radar.

In 2023, most Jewish students and Hillel staff that I’ve spoken to about Kahane’s past here have understandably reacted with shock upon hearing how warmly the campus Jewish community received him just a few decades ago. I was also rattled when I first stumbled upon these articles in the Mitzpeh archive last year, but I must admit, his past popularity is unfortunately beginning to make more sense to me as I watch his ideas gain more traction in an Israel devastated by the October 7 massacre.

The current head of Kahane’s yeshiva in Jerusalem, Rabbi Yehuda Kreuzer, along with dozens of other rabbis, cosigned a letter to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu during the first phase of Israel’s war in Gaza, urging the wartime leader to bomb the beleaguered enclave’s largest hospital which Israel says sits over an underground Hamas base, without any regard for civilians.

While I know many in Israel who have faced arrest over the past few weeks for dissenting against the war’s civilian casualties, police are allowing right-wing activists to chase down Arab college students in Netanya, calling for their deaths. As the line between combatant and civilian blurs in the Gaza Strip, it does so within Israel as well, putting the country’s Arab minority in an impossible situation.

Kreuzer rejoiced earlier this year over the increasing legitimacy Israeli society is lending to Kahane’s teachings. He attributed this uptick to both an “existential danger” — referring euphemistically to Arabs — which an increasing number of Israeli Jews now feel threatens them, and Ben Gvir’s role in the current government.

“Suddenly, we have ministers. This [Kahane’s thought] isn’t outside the camp anymore,” he said. “We were always on the fringes, and now we’ve entered the center.”

Kreuzer is correct. Meir Kahane has been dead for decades, but his legacy is alive and well in Israel. After his long history in America, including on UMD’s campus, we’ve forgotten all about him. But to understand what’s happening today, we need to remember.