It was a rainy first day at Camp Kinder Ring in upstate New York, the face-down canoes on the beach of Lake Sylvan peppered with droplets only known to late summer. A large tree had fallen and tore the Arthur Goodzeit Adventure Center signpost from the earth. All the young campers who were here for the summer had left on Aug. 13, a day before our arrival.

On a generous scholarship established by The Workers Circle, 14 other students and I comprised the College Network of the progressive Jewish organization’s annual Trip to Yiddishland. The weeklong trip to Camp Kinder Ring has been around, formally, for 14 years with The Workers Circle as the host, but, for the first time, yunge mentshn (“young people”) would fill the bunks at no cost: as scholars, friends, and college students from all over the globe, joined together in Yiddish language, literature, song, and theater workshops and communal camp life.

The once-socialist Workers Circle (“Der Arbeter Ring” in Yiddish) was founded over 100 years ago in New York City by Yiddish-speaking immigrants, who devoted their lives to activism and social justice — for and beyond the Jewish community. Since then, the non-profit’s programming has evolved: year-round Yiddish language classes, public-facing events, and online Yiddish song resources. Up until the 1950s, The Workers Circle had no significant presence on campuses, and out of this absence, youth programs were born: to engage the next generations of Jewish activists, informed by a dominant Yiddish and diaspora culture. The College Network itself, however, was organized in 2020.

The 2023 Trip to Yiddishland was, perhaps, the first attempt to introduce the combination of Yiddishkeit and activism to a more global college network. Up to then, the centralized forces of College Network students in New York and on the East Coast had already begun to enact change, like in the Young Jews for a Green New Deal who have joined climate marches and written to legislators. More recently, College Network members have joined demonstrations on Capitol Hill and beyond, advocating for peace and justice in the wake of the Israel-Hamas war. On this trip, for a week, students from all corners of the world would convene: an artist from Austria, a co-founder of March for Our Lives, Western Massachusetts Yiddishists, Ivy League nerds, a poetic Messiah claimant, the self-proclaimed “toss-away useless lesbian,” and burgeoning theater stars.

From Generation to Generation: Fun dor tsu dor

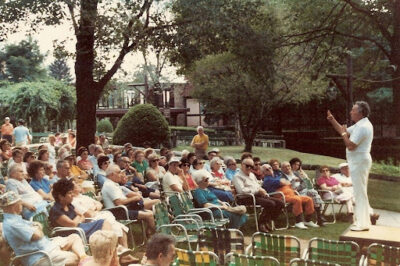

Of course, the College Network on this summer’s Trip to Yiddishland were not the only campers: nearly 100 others joined us, ranging from the young children of Yiddish family dynasties to the Golda Shore. Now in her 90s, Golda has been attending The Workers Circle’s trip since childhood. Personally, this was the first multi-generational Yiddish-learning environment I had ever entered. In other programs devoted to teaching and living Yiddish culture, such as the Yiddish Book Center’s annual Steiner Summer Yiddish Program, participants are primarily limited to college students. But when people of all ages are present, Yiddish makes more sense — becoming more representative of the range of wisdoms that come with any Jewish community or culture.

Trip participant Evan Price, a senior at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, never felt immediately connected to a Jewish community, despite growing up Orthodox. But, for him, the trip’s multi-generational Jewish landscape felt reaffirming. “It was really nice to meet older people who had more radical politics than me in some ways and who were really invested in a progressive vision of Judaism,” he said. “In my experience, progressive Jewish spaces have always been really young.”

“[The older participants] provide sort of a surrogate sense of Jewish elders that I don’t personally have in those family relationships,” trip participant Josh “Yoshke” Horowitz, a recent graduate of New York University, told me. Yoshke, who lost his grandparents when he was young, has dedicated himself to the study of Yiddish to keep his family’s history. Yoshke also attended the young environment of the Steiner Summer Yiddish Program, which he compared to Yiddishland. “[Yiddishland] is very reminiscent of the Catskills retreats, in a way that Steiner is reminiscent of being in the woods or whatever — there’s trees and such. But everyone is 20.”

Yoshke refers to what has become of the “Borscht Belt,” a historical region of the Catskill Mountains — of which Camp Kinder Ring is part — once home to thriving bungalow colonies and resorts for Yiddish-speaking Jewish communities in the 20th century. At a time when Jews were barred from the ritzy New York City hotels and beaches, the Catskills were home to summer freedom, with over 1,000 resorts operating within the Belt. Many of the older Yiddishland participants, like Golda, can remember this time in history. To be a College Network camper is to honor and yet reconceive this rich and storied Yiddish camp life.

“[Yiddishland] feels more connected to the historical continuity of Yiddish,” Yoshke said.

Near the end of the weeklong program, a majority of Yiddishland participants gathered lakeside in the light of dusk to sing Yiddish folksongs and make s’mores around a campfire. New-age Yiddish actor icon Michael “Mikhl” Yashinsky handed me and other College Network campers potatoes to grill in the flames. For Barnard College sophomore and trip participant Sally Kaye, the bonfire was her proudest moment of the week — where Jewish unity and understanding, across years, were discovered.

“I felt like I was really being treated like an adult person. And I thought that it really exemplified what Yiddishland was like,” she said. “At the campfire where everyone was singing … it felt like everybody was there together, as one being, as one voice.”

After World War II, Jewish camp life has often been unaccepting or damaging to queer/LGBTQ+ campers. At Yiddishland, the older participants were more understanding, perhaps given their alignment with more progressive beliefs. “They’re all hippies,” Sally said. “They just seem so much more willing to accept the gay and trans people of our [College Network] than, at least, the older Jewish people in my family.”

For me, as well, knowing and communicating with the “Yiddish elders” is an important dedication to Yiddish memory. Golda, on the morning of the last day of the program, handed me a lined notepad where Yoshke, our friend Dina, and I scribbled our phone numbers and email addresses to stay in touch. A teary-eyed Golda, grabbing our hands and gesticulating with hers clasped, told us how much she would long for us — the College Network “kids” — to come back on next year’s trip.

“Listen — everyone here is old. I know them already. You’ve all brought such life,” she told us. “You have to come back next year, and the year after, and the year after.”

The College “Network”

My phone had died in the cold thrall of New York City. I somehow made it, anyway, to the East Village Indian restaurant where the College Network campers were destined to reunite since our fling in August. We were in the city on a mission: The potato-wielding Mikhl, and Yoshke — two of our very own Yiddishland participants — were putting on the first American Yiddish drama in seven decades, Di psure loyt Khaim (“The Gospel According to Chaim”), a story about the translator of the New Testament into Yiddish. We had all ventured to New York to see the show’s preview on Dec. 21, almost four months after our initial meeting. Yoshke would be making his Yiddish theater debut.

Our group took up almost a whole row at the small off-off-Broadway Theater for the New City. Sat next to me at the terminus of the row was a journalist who looked surprised. “Are you the 10 Yiddishist friends of Mikhl’s?” he asked.

To say we were perceived as a collective would be an understatement. And, at the end of it all, I suppose we are his 10 Yiddishist friends.

The journalist’s comment reminded me of what Sally had said about the College Network’s positioning against the rest of the Yiddish world — the generations with which we have coalesced. “[The people at Yiddishland] are in the Yiddish community. Everyone is in the community. You’re not under these people.” To have such a “non-hierarchical structure,” as Sally puts it, is a blessing.

Since the beginning of my first year in college, I have learned and lived Yiddish in universities and in summer programs such as The Workers Circle’s Trip to Yiddishland. And this summer, I attended the long-coveted Jewish summer camp for the first time. I slept on a musty bunk, its wooden supports inscribed with bygone love messages. I played volleyball with the children of klezmer stars. I drank whiskey in the dark mess hall on Shabbos as a rabbi led us through nigunim. I felt the Yiddish — the Jewish Yiddish — catapult through my lungs and my ears, and I know that I will always have that for life, even when my college studies are to the fore.

“Going to Yiddishland for the first time in my adult life made me think of the possibility that I could be involved in a Jewish community,” Evan said. “And it was really special to have that experience.”