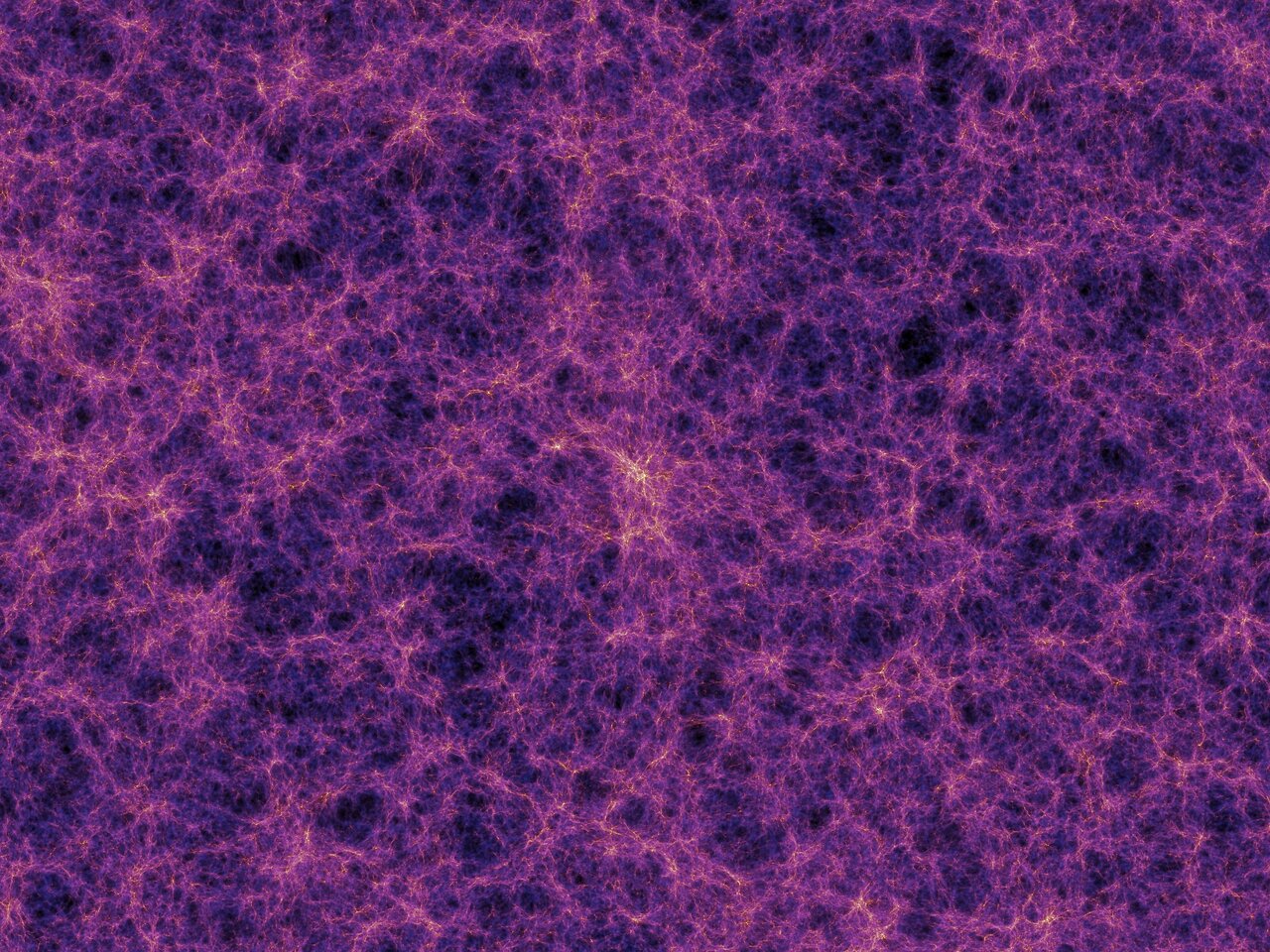

Artist’s rendition of the Cosmic Web – the structure of galaxies, galaxy clusters, and dark matter naturally formed by gravity across the Universe.

Credit: Volker Springel (Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics) et al.

If you go camping in the Southern California desert, outdoorsy experts will tell you to bring heavy blankets and check your shoes for scorpions. But while you’re preparing for tent upkeep and hiking trips, you might forget to look up. At night, without the Los Angeles light pollution, stars peek out of the darkness and the spiral arms of the Milky Way throw themselves across the sky.

If you step outside your tent and look up, past the spiky vegetation and mountains of rock, it feels as if your line of sight could extend forever. I first experienced this vastness on a trip to Joshua Tree in middle school, having never seen a sky fully peppered with stars. I’ve since taken many more of these trips, in pursuit of a particularly dark patch of the heavens. When I bought an eight-inch telescope in high school, the summer sky and its viewable planets became close friends. Watching the planets traverse the sky, follow-the-leader style, how could I not fall in line?

Many years later, I am both an astronomer and a Jew: a follower of the “religion of science” and the “science of religion.” And while I’m not a particularly devout Jew, my Jewish perspective and upbringing have largely informed my devotion to the Universe.

Oneness

In college, I study astrophysics; I explore galaxies and solar systems and planet formation and, of course, the cosmic web that connects them all. When one zooms out on our cosmic neighbors and examines the supercluster which we are part of, it is hard to believe that there isn’t a greater oneness at work. Maybe not a supreme or benevolent being, but a connection that reaches its gaseous arms across the natural world. Forget other solar systems or even far-away nebulae: our Earth is a tiny blip in the larger pattern of spindly arms of gas and dark matter which connect massive galaxies all around us.

Forgetting what we can see (and dark matter, which we cannot see), this “oneness” can be found in audible wavelengths. When astronomers listen closely, we can hear the cosmic symphony of gravitational waves rippling across the Universe, nearby pulsars can be heard beating like hearts, and we continue to “hear” radiation from the Cosmic Microwave Background, aging back to the beginning of our Universe. The cosmos is noisy, and it’s singing to us.

You might say, “I’ve never heard the Universe.” But this is purposeful. This year, I attended a lecture at Wesleyan University where Nobel Prize-winning physicist Barry Barish spoke with our class of astronomers. When asked about audible wavelengths throughout the universe, Dr. Barish noted: our ears were cleverly designed to listen at frequencies where the “Earth is quietest.” We have evolved to communicate in the ranges of silence, so that we can understand one another through the noise. This is how in tune humans are with the cosmic symphony.

This oneness is present at the very core of our Jewish tradition, particularly in the Shema. The Shema says there is only one Lord, whatever that may mean to you; one greater human condition, one greater force of nature, or perhaps one greater Universe. I personally enjoy a less human-centric version of “God,” where the binding forces between people are more Newtonian than holy. But there is no doubt that we are a part of something bigger. We have a place in the cosmic story, being made from the same atoms and elements as the stars and planets. It is true that we are formed from the “dust of the Earth” – we are descendants of space stuff, whether your origin story starts with an apple or a bang.

In her book Astrotopia: The Dangerous Religion of the Corporate Space Race, religion professor Mary-Jane Rubenstein describes the pull of the cosmos as “mythic”. And she’s right: there is something truly spiritual about our cosmos – it has a God-like ability to make you feel small. As Rubenstein beautifully writes, “Innumerable suns warming scadzillions of planets, with oceans and dust storms and cloud microbes and who knows what else, all in constant motion through infinite space and time, and here you are, making a cheese sandwich, nowhere in particular.”

Cosmic Reverence

More than this, though, my Judaism has encouraged me to respect our cosmos. Jews have long held the natural world in high regard. By keeping kosher, Jews seek a oneness and balance with nature, where everything consumed is respected and life-giving is sacred. We honor trees and fruit and ecology on Tu Bishvat, which has more modernly become an environmentalist holiday. Tu Bishvat consists of great replanting efforts and sustainability in modern Jewish thought – it’s a planetary effort. Jews also honor the Tree of Life, a figure that’s been present in my education since the early years of Hebrew school. A 13th century rabbinic interpretation of the Tree of Life describes it particularly cosmically:

“Beneath it are the disciples of the Sages who expounded the Torah, each of them possessing two chambers, one of the stars and the other of the sun and moon… Inside it are three hundred and ten worlds.”

But there are numerous plants which guide Jewish cosmic understanding: the burning bush, the kikayon, the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Bad, and more. For centuries, the natural world has guided Jewish spirituality, and in turn we have treated the natural world with reverence.

There is also, of course, tikkun olam. Tikkun olam urges Jews to “repair the world” in every sense imaginable. This involves social activism and caring for the people around us, but it also means literally repairing the planet: the planet and all other creation. Tikkun olam commands a profound respect for the natural world and emphasizes the human position as an active participant in it. As the planet gears up to put human boots on Mars, this respect for the natural world will begin to extend to the desolate surfaces of other planets. Tikkun olam certainly informs my own feelings about human ventures in space; I believe that the protection of Mars, Earth, and the lunar surface from private human interests are of peak importance. Most notably worrying is the increasing layer of space junk that chokes low Earth orbit (LEO), and Elon Musk’s plans to “Nuke Mars” – among other anti-tikkun and pro-imperialist efforts. When humans become residents of the greater cosmos, we will have to extend our worldly religious values to this cosmos as well. It is not ours, it is something bigger and we must honor that.

Some scientists – and particularly astrophysicists – can get caught up in semantics and titles. What kind of “ist” are you, and what kind of God do you believe in? Are you spiritual or scientific? Instead, I think that spirituality can provide an excellent framework for the value systems that we apply to the natural world around us, and ultimately the greater cosmos. I feel particularly connected to my Judaism when finding purpose, meaning, and community (all very important in Jewish tradition) in my science. My awe and devotion to the Universe, as well as the space that it holds in my Judaism, is helpfully described by astronomer Carl Sagan:

“Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality.”