For over a month, 74-year-old Vivian Silver was presumed to have been among those held hostage in Gaza.

Last week, it was discovered that Vivian was killed in the Hamas attack on October 7th, at Kibbutz Beeri.

A lifelong peace activist, Vivian began her activism as a founding leader of the Jewish Student Press Service – the organization now known as New Voices Magazine.

In revisiting the origins of her work as a key leader in the Jewish student movement of the 1970s, we honor her legacy – both in Israel-Palestine, and across US college campuses.

“I always knew I had a mom who was kick-ass,” Chen Zeigen said of his mother, renowned peace activist Vivian Silver. “She never shied away from confrontation. She was almost fearless in that regard.”

She has been described as not only fearless, but warm, passionate, driven, kind, and intelligent. And yet, these words barely begin to encapsulate Vivian, whose life has become a beacon of hope for so many during the past month. Her ability to hold complexity while remaining strong in her vision for peace has inspired those in the Jewish community and beyond.

Born in Winnipeg, Canada, Vivian moved to Israel in her twenties and was one of the founders of Kibbutz Gezer, alongside other members of a garin (seed/group) from the Habonim Dror movement. Since then, Vivian spent her life dedicated to fostering peace between Israelis and Palestinians. She was the co-executive director of the Arab-Jewish Center for Equality, Empowerment, and Cooperation, which consists of a team of Arabs and Jews who “work together to create a shared society.” In 2014, Vivian co-founded Women Wage Peace – an organization that centers women in promoting “a non-violent, respectful, and mutually accepted solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.” As a volunteer for Road to Recovery, she would regularly drive to Gaza and bring Palestinians who needed medical care to Israeli hospitals. Vivian also founded a group called Creating Peace that forms business collaborations between Palestinian, Arab-Israeli, and Jewish-Israeli artisans.

But before Vivian embarked on the journey to start a kibbutz and work toward peace, she was a student leader and activist, gathering and nurturing the seeds of Jewish student voices from across the country. Conversations with her friends and collaborators have the same consensus: her time as a student organizer laid the groundwork for a lifetime of devoted activism.

“We build Jews, not buildings!”

In May of 1969, Jewish student activists came together at the World Union of Jewish Students (WUJS) to discuss the state of Judaism among American youth and address issues that mattered to them. “From this conference arose the North American Jewish Students Network, a communications, information and resource arm of the WUJS,” wrote Sarah Wolf for New Voices. Following this watershed moment, the Jewish Student Press Service (JSPS) was founded in 1970 as a wire service, which connected and provided content for independent Jewish magazines and newspapers on college campuses across the country. Today, New Voices is the official magazine of the JSPS.

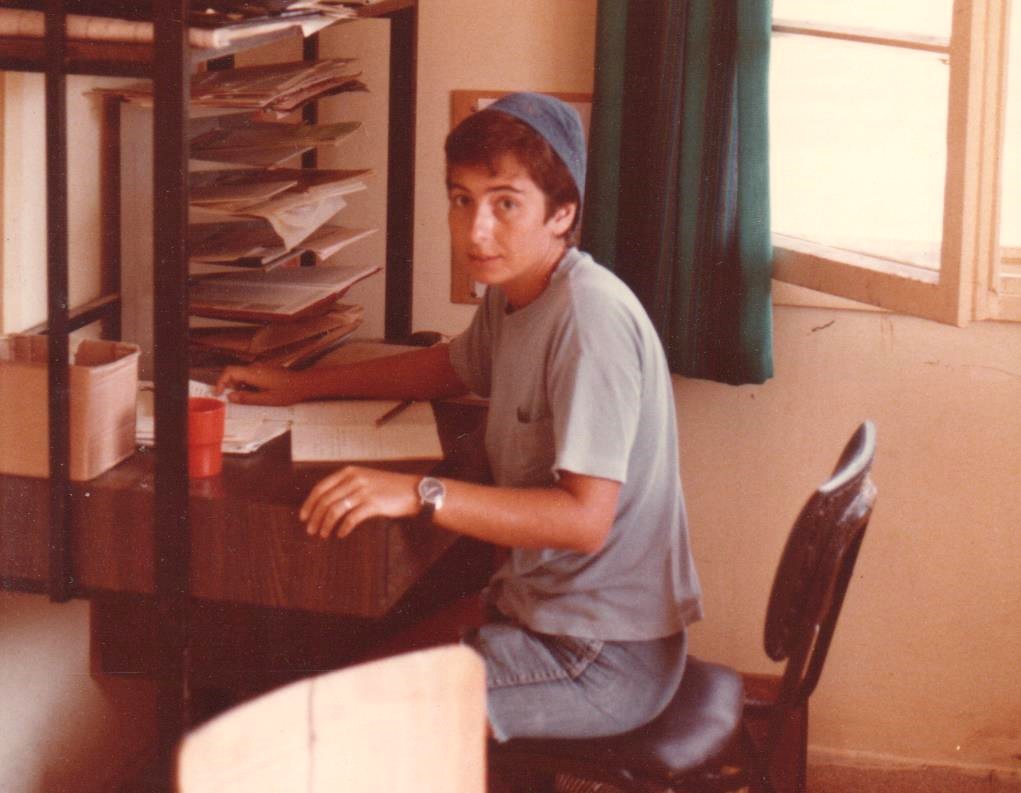

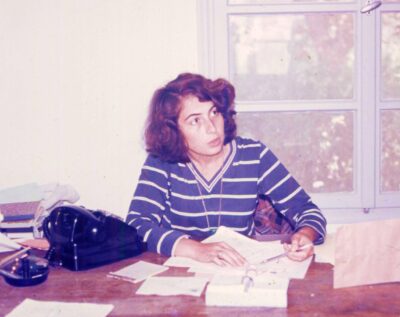

In 1972, Vivian Silver took on the role of administrator of the Press Service, making up half of their two-person staff. She ran the national, grassroots organization alongside Rabbi Gerry Serota, who was JSPS editor at the time.

In this role, Vivian was tasked with liaising Jewish student newspapers from all across the country, convening journalists at an annual conference in New York City to discuss pressing domestic and international issues, and managing the administrative duties of the wire service.

Ken Bob, a member of the Berkeley Radical Jewish Union, met Vivian at this annual conference. He was blown away by not only her vision and ideology, but also by her ability to constantly get things done in service of that vision.

“Back then, it was called ‘administrator’,” said Bob. “Today, we’d call it CEO.”

“She is one of the most inventive activists I’ve ever known,” said Samuel Norich, current JSPS board member and chair of the board from 1972-74. “She set high goals, and worked on bringing others to bear to make them happen, and bringing networks to bear, and bringing funds to bear.”

But even so, funds were limited for grassroots causes, and being at the forefront of student organizing was far from a glamorous job. The Network, Press Service, and Jewish Student Appeal “shared a mouse-infested loft on West 27th Street, in very close quarters,” recalled Susan Dessel, the Executive Director of the North American Jewish Students’ Appeal at the time. “Those jobs were more than just jobs, they were a lifestyle,” she shared, smiling fondly. “It was twenty-four seven. It was a passion, and that was why we were doing it.” Dessel remembers days and nights of long, meandering conversations about their lives, what kind of futures they envisioned, and “wanting the Jewish community to be a better place, particularly for women.”

When speaking with Vivian’s friends and colleagues from JSPS, I was struck by how the issues they fought for have reverberated throughout time – we hear echoes of these fights in student activism today.

“Within the American Jewish community, we felt that they were underfunding education, and other Jewish communal priorities,” Bob explained. “We were also trying to push the community on general domestic issues, such as racism and the war in Vietnam.”

Vivian was a leader in challenging the concentration of power and resources in the Jewish world. “She wanted to make structural changes. Her approach was to say that our Jewish community is much more expansive than just people who have a lot of money. There are so many different ways of being a full participant,” said Dessel. “We build Jews, not buildings!” was a rallying cry of Vivian and her peers.

Instead of simply speaking about these issues, Vivian took action to create the new realities that student organizers had dreamed of. Through the North American Jewish Student Network, Vivian was part of organizing the Coalition for Advancement in Jewish Education (CAJE) – dubbed “the Jewish Woodstock,” which inspired future conferences like Limmud. She was active in the movement to help Soviet Jewry, working closely with the North American Jewish Students Appeal. She also raised funds from federations and foundations to redistribute to grassroots and student-run causes.

Alongside the “New Left,” Vivian and the Jewish Students Network mobilized around Civil Rights, the Vietnam War, and other political causes in the early 70s. But after the Six Day War, supporting Israel was no longer considered the progressive position within the New Left. This shift had repercussions for Jewish students, especially those with connections to Israel.

“There’s a similarity between what Jewish students are experiencing now, and what we experienced after the Six Day War,” said Bob. “There was this sense that Jews no longer belonged on the left.”

He and David De Nola, editors of The Berkeley Jewish Radical, recall being denied a Jewish delegation at an anti-war march “because we were Zionists – even though we were radical Zionists.”

But the Berkeley Jewish Radical’s editors – along with Jewish student writers from across the country – felt at home with the Jewish Student Press Service. Vivian made sure Jewish students knew they had a place to go, listening and uplifting their concerns from across the country. She had a unique ability to see multiple truths while maintaining ideological consistency.

Vivian believed that “a solution had to be found that provided for a livable life for both communities, whether together or separately,” Norich recalls. In the immediate aftermath of war, she and her peers understood that occupying the West Bank was not a sustainable option. She published and distributed work from Jewish student newspapers that called for Palestinian self-determination and covered radical leftist Israeli movements, such as the Israeli Black Panthers. Despite a feeling of Jewish exclusion from the left, nothing stopped Vivian from fiercely advocating for peace, and for the dignity and lives of Palestinians and Israelis alike.

Fighting for feminism, in theory and practice

Vivian devoted herself to feminist work. Even as a student, she was at the forefront of creating systemic change for Jewish women. “The first time I saw Vivian in action was at the Network convention with Jewish student groups from across the country,” shared Shifra Bronznick, who would soon become Network’s Executive Director. Bronznick had been noticed as a strong leader at her Jewish high school, and was invited to attend the event. At this convention, there was an election to set the Network’s priorities for the year. But right before the election, the women broke off on their own to convene an independent caucus. “Having gone to an Orthodox day school, I was blown away!” Bronznick laughed.

The women present advocated for the urgent importance of gender equity and voted to create a women-only conference through The Jewish Student Network. Thus was born the first National Conference of Jewish Women, which took place in New York in 1973.

“Even though we weren’t observant,” Dessel said, “it was really important that women were able to study. When the first woman rabbi was ordained, it was such exciting stuff!” Dessel pointed out that while this may not sound exciting today, it was groundbreaking at the time.

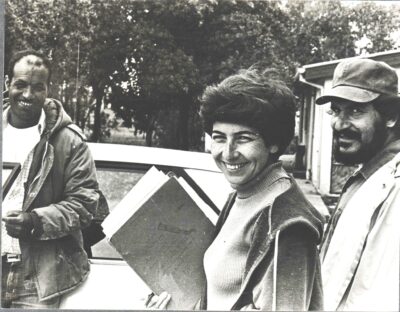

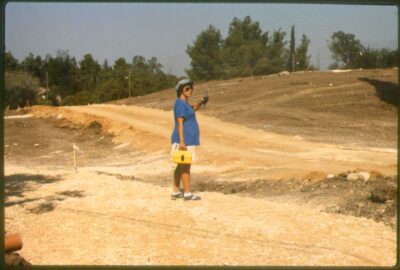

One year later, Vivian made the move to Israel and began embodying her feminist values in new ways at Kibbutz Gezer. David De Nola, a friend who lived on the kibbutz with Vivian, recalls that she held a number of leadership positions, including being the liaison to major government officials.

“She took up a lot of tasks at the kibbutz that women didn’t do. She learned about them quickly, and wanted to make sure that her work at the kibbutz was not gendered,” said Bronznick, fondly.

Vivian was in charge of infrastructure, overseeing construction and architecture – kibbutz roles that were not held by women at the time. “I think they tried to put her as a caretaker in the ‘children houses,’ but she quickly refused to do it,” her son, Chen, said. “She had a little old beat up Volkswagen Beetle that she would drive around the kibbutz – she called it her Rolls Royce.”

Sometimes, Vivian received pushback against her refusal to adhere to gender roles, but none of that fazed her. “You’re talking about a real misogynistic society,” De Nola said, “but nobody pushes her around.”

A different kind of leader

Family and friends cite Vivian’s incredibly ideological consistency throughout her life. Not only did she live by her values, but she modeled for others – including her sons, Chen and Yonatan – by example. When asked what he has learned from his mother, Chen said: “All of the values I hold, such as gender equality – which was very much instilled in us as children. Most of all, I learned to seek peaceful solutions, to see common ground with people who are different from us.”

Building serious partnerships – as well as genuine and lasting friendships – with Palestinians was essential for Vivian, both to her work in Women Wage Peace, and in her life. “She developed close relationships with many people from Gaza who worked on the kibbutz in the 90s,” Chen shared. When the border closed, she drove into Gaza to deliver their wages. She stayed in close contact with them over the years – sending money when times were hard, calling each other on holidays, and checking in whenever there were surges in violence.

In such a constantly tense political climate, Vivian was aware of the existing power dynamics and approached these relationships with care. She spoke both Hebrew and Arabic fluently, and crucially, “she has a loving, kind heart,” said Bronznick. “This is part of what allowed her to traverse some of the land mines that can exist.”

“Vivian was always such a quiet leader,” Dessel remarked. “There’s something about her that is so special. Anything she does, she does because of what it is – not for her ego.” Throughout her life, this humble approach to leadership drew people to her, both as a student organizer and as a kibbutz leader. Whether navigating gender injustices, violence in Israel-Palestine, or classism in the American Jewish community, “she just knows how to cut through to what’s at the heart of something.”

The front page of the Women Wage Peace website says, “Yes, there’s another way.” Vivian embodied this possibility. In a time when peace feels remarkably out of reach, we find comfort and hope in Vivian’s legacy. Her vision saw beyond boundaries and broke through binaries. As a student, leader, and activist, she spent her life building a world that she wanted to see: one with dignity and justice for all.

All photos credited to the Kibbutz Gezer Archive.