Fancy Feast is giving you exactly what you paid for. Whether you’re seeking a velvety, intimate peak behind the curtains of New York nightlife, a stark illustration of the treatment of sex-retailers, or a poignant treatise on pleasure’s place in activism, the Jewish burlesque icon delivers a scintillating, blisteringly funny, intimate collection of stories that stick in your brain like hard candy on teeth.

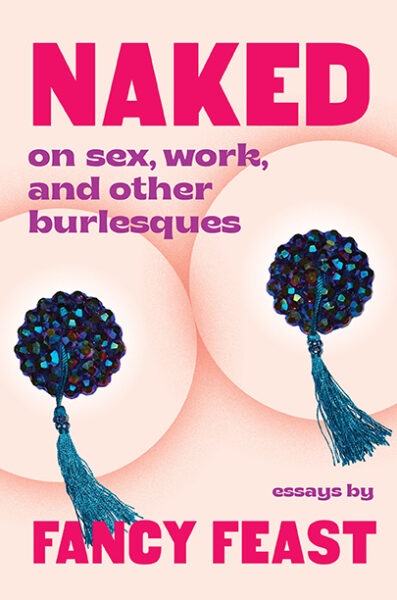

Fancy is a denizen of the Lower East Side’s underbelly, a provocateur whose riveting, scandalous acts have been a fixture of the burlesque scene for years. After falling in love with burlesque through a high school production of Cabaret, (the costume from this production still hangs proudly in her closet), she nurtured her calling for the art form first from the audience and eventually from center stage itself. A jill-of-all-trades, she is a former Miss Coney Island, a therapist, a social worker, and a creative programmer whose hits include the Fuck You Revue. Her most recent book – Naked: On Sex, Work, and Other Burlesques – allows readers to glimpse the intimate details of her many lives. The unflinchingly candid essay collection touches on a wide remit of her talents, from harrowing experiences in sex-shop retail to sagas as a phone-sex worker during the pandemic. With every tale, Fancy explores her experiences as not only a performer, but as a person who is deeply engaged with justice and fat liberation. The pace ranges from frank, stark depictions of life between shows to in-the-know secrets of the stage.

I devoured the work in half a day and felt nourished, challenged, and inspired. As an “unmistakably Jewish” performer in conversation with an equally as Jewish magazine, our conversation ranged from playing for non-Jewish audiences to the pressures of continuity culture.

J: Hey Fancy, how’s it going? On my side, honestly, reading your book was probably the highlight of my week. We’re definitely going through it right now, so thank you so much for that.

F: Aw, I mean, I’m not happy to hear that that was the highlight, but I’m so glad you liked it. Thank you.

J: You speak candidly about being “an unmistakably Jewish person,” a “dark haired Jewess with a hormone imbalance.” Could you speak about Jewish beauty in conjunction with standards in the biz, fat joy, and sexual performance?

F: One of the first texts I read on the topic was Kosher Sex by Shmuley Boteach – yikes. It was on my parents shelf and it helped inform some of my early concepts of sexuality. I think whenever you talk about Jews in general, we love to be so proud of how sex positive we are. Jewish people will always go, “oh, well, the Catholics have their shame, but it’s actually a mitzvah!” So, I think I grew up understanding that at least sexual discourse was treated like all other discourse according to Judaism – openly discussed, and integrated into everyday life. But in terms of desirability, that was a stickier wicket, because I didn’t see Jewish bodies being treated as objects or subjects of sexual desire. It was all Janice from Friends or Woody Allen; I didn’t find myself being subjectified in the media. But fortunately, with burlesque and vaudeville, there’s always been a large contingent of Jewish performers and Jewish showgirls, it really felt like I could continue to be in conversation with the sexy Jewish people who came before me.

J: There is theory wound through everything you’ve written. With regard to the sociological questions in the book, what are some things you’d like your readers to walk away thinking about?

F: I don’t feel as prescriptive about what the takeaway is here. I don’t know if that’s a function of having taken off my clothes for strangers for many years – whatever you take, as long as you paid for admission, I don’t really care. Shock and sex provide a trojan horse to have these other kinds of experiences sneak through, whether it’s about how to interrogate our own desires, whether it’s our feelings about engaging in community experiences and live performance, or whether it’s about respectability politics. It would be great if something got in there, like: “hmm… maybe I should stop being so shitty to fat people.” It’s sort of a sizzler buffet. I hope the book being written in a way that is intentionally accessible provides the sort of steam-tray of theoretical experience that people can just pick and choose from wherever they feel most resonant.

J: In the past New Voices has written about the Jewish drive for reproduction, and the pressure for continuity. How does that impact those who are not performing the “ideal” of continuity (such as those having sex for pleasure, those unable to have kids, who aren’t interested in kids)?

F: I love this question. I mean, I’m a child of the 90s. I was in religious school at a time when the social gatherings would be sleepovers, where we would get everyone together and all the adults would leave the room. I didn’t understand it intellectually, but I understood something was going on that made me feel uncomfortable. Later on in my adolescence I realized: oh no, actually this is creepy. And the emphasis on childbearing and pregnancy and repopulation as the divine responsibility and highest use of a woman’s body creeped me way out. It was never my intention or desire to be a brood mare for any cause. I really chafed against that. It’s interesting to see where that still shows up when I’m asked about whether or not I have children or what my choices are, but then also, because it’s something I was able to find opposition with in my adulthood, it becomes something fun to play with! Having queer sex feels really expansive, and threatens that status quo. It feels like worlds open up, like so much more is possible and there is so much to be done with what is already on earth than what is coming from our ovaries.

J: You write in a beautiful passage: “Moving toward pleasure is only useful if it also moves us toward liberation. Which is why I sometimes say, when I’m feeling contrarian, that no one should have a body. I’ll wave my Jewish hands over this sentiment and say a combination of prayer and curse: may we all become a fine, damp mist.” (88) Do you feel your Judaism as embodied or ephemeral – is it the thing that defines your hands or the curse you cast out of it? Or both?

F: I think I experience my Jewishness in a very embodied way. At times my relationship to G-d has been tenuous and non-existent, and is not currently something I believe in. But experiencing ancestral and historical Jewishness through the phenotypic presentation of my body has always felt like the easiest way in. When other aspects of Jewishness have been tainted or tenuous, or when I haven’t trusted other people around Jewishness, the ephemeral nature of spirituality becomes hard to access. But being grounded in my body and understanding it as a Jewish body has been the conduit. I’m not going to shul, but I perform Jewishness through my burlesque acts.

J: How does working in Jewish space, or with Jewish creatives feel to you? As a performer whose Judaism is not explicitly part of your act, how do you find the culture bubbling up in your performances?

F: There’s something so lovely about working with other Jewish people, there’s shared language beyond language, things that didn’t have to be explained, a sense of kinship and belonging that would be tested but would still be there for me. I love Jews! I love being around Jews!

It’s very different to perform Judaism for non-Jewish people, and that’s something I have some pain around. I was one of a very small handful of Jewish people at school, and as part of the diversity initiative, I would be called upon to speak in front of the whole school and describe my traditions… it had this sort of stark anthropological othering effect. I ended up with a lot of intrusive interest in my traditions that didn’t feel good. So now, to represent Judaism on stage, it’s two things: I get to be confrontational and presentational. I have authorship over what gets transmitted. And then also I’m not so far out of my milieu. At the end of the day I’m a Jewish person, I’m in New York, performing most often in the Lower East Side; there’s something so Jewish about all of that. Even if I’m being perceived by Christian people… we’re like two blocks away from Yonah Schimmel, come on! There’s a whole other set of jokes for Jewish people of course. I love hearing all the different kinds of laughter that happen depending on who’s watching.

F: Their entertainment is the goal, if I’m not being entertaining, it doesn’t matter what else is happening. When I have creative control, or authorship over a performance or show, for example the Fuck You Revue which I used to program monthly, it would be important to us to have work that wasn’t just representing a radical politic and doing nothing with it. People could experience shock, catharsis, and connection and representation through the acts that we booked, but we would also donate a portion of our proceeds to activist groups and mutual aid funds. We didn’t want our work to be mistaken as radical and have that be enough, you know? We would ask our audiences to write holiday postcards to incarcerated sex workers, it felt like it was all part of the same ecosystem, that having our same values, if we’re not going to do anything with them, is meaningless. I think a lot of my legitimate life is also a negotiation of that now. I work in mental health. I work with underserved populations. That’s not activism – or I don’t consider it as such. It pays my bills and I am beholden to the state for my certification, how radical is that shit? Always a step forward and a step back. I’ve been trying to act more in accordance with my values these days, I’m trying to find where my integrity is and do something about it.

Fancy Feast’s collection of essays, NAKED: on sex, work, and other burlesques hit the shelves on Oct 10, 2023, and you can grab a copy here.