I haven’t entered a synagogue for two years.

Two years ago, my rabbi told me I was “disrespecting G-d” with my gender identity. “G-d gave you the blessing of womanhood,” she said, “and you are rejecting it.”

That synagogue was the only one in town. There was nowhere else for me to go. And so, in that moment, I became isolated from my Jewish community.

And I am not the only one.

Mandy, a half-Japanese, half-Ashkenazi gender-non-conforming lesbian Jew, shared their story of isolation from Jewish prayer spaces. “My family are conservative Jews,” they said. “And I’ve always felt alienated by the very traditional Chabad synagogues we attend every so often. I’m fortunate to have never felt threatened or unsafe in Jewish spaces because of my queerness, but I definitely feel a sense of otherness, which has contributed to a personal disconnect from communal prayer.”

This sense of painful otherness is a persistent thread through stories of queer Jews seeking to connect in Jewish prayer spaces. When surveying college-age queer Jews, many expressed a struggle to fit into more traditional places. “I constantly feel like I’m too religious for queer Jewish spaces, and way too trans for Orthodox spaces,” one community member shared. “We attended a modern orthodox shul as a butch4butch couple,” another stated, “and people wouldn’t even look at us.”

Meanwhile, others expressed that regardless of denomination, their queerness or transness was met with hostility: “As a trans person, I always felt the need to tell my non-Jewish friends how inclusive my synagogue is. In reality, even though it is Reform, people still give dirty and confused looks and whispers. Also, a lot of language used during services is so gendered.”

For those who did not experience homophobia, there is still a sense of not fully fitting in, or of queerness being ignored. “I don’t think my synagogue is homophobic,” Talia Barnoy shared. “I think they do a good job of supporting their queer congregants as far as I know. It’s just that I think that they might be queer avoidant. In Hebrew school I was told, in indirect words, that God was genderless but never what that might mean for me. We never learned about Ruth and Naomi or David and Jonathan but I heard the story of Rachel and Leah over and over again… I can’t remember having space to explore my identity growing up, outside of the stories decided upon.”

But the presence of queer leaders, along with the existence of spaces by-and-for queer and trans Jews, can have profound impacts. “I grew up with a lesbian rabbi,” a community member shared. “I never felt more supported or safe than in my synagogue.” Ariel Kates, after an experience with a transphobic rabbi, attended services at an explicitly queer synagogue. “Later, at the queer synagogue,” Ariel said, “I really felt like a kindred misfit in that beautiful place, even if the davening didn’t speak to me as much.”

Through my own experience and hearing others’ stories, it is clear that LGBTQ+ young adults often become isolated from their religious communities. But Keshet – a grassroots organization fighting for LGBTQ+ inclusion in Jewish life – is seeking to change that. Their newest project gives LGBTQ+ young adults a way to actively participate in the holiest day of the week: Shabbat.

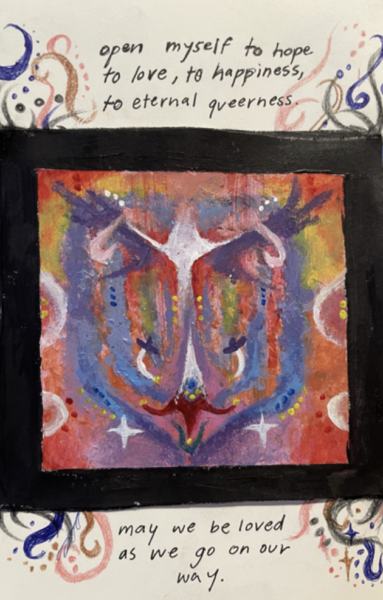

Keshet is publishing a siddur (prayer book) insert filled with art, writing, and QR codes to videos and music – inspired by Shabbat and siddurim – all created by LGBTQ+ Jews from age 13 to 24. The siddur insert can be printed out by anyone to add to their Shabbat and holiday practices.

“There are so many stories in the Torah that inherently lend themselves to queer readings,” said Julia Hegele, founder of Golem Zine. “There are queer characters and themes and emotions: stories about moving past exclusion, or finding community in non-traditional places. And though those are also Jewish feelings, they are implicitly tied to queer experiences. Having a document that binds all of those together in a holy context is a big deal.” Julia explained that many of her queer friends experienced hardships when trying to participate in religious Jewish life. “They didn’t see themselves reflected in holy texts, or in the way their congregation prayed or spoke about the basics of love and community,” she reflected. ”Being able to have something like this for people who might be struggling or wanting to learn more about themselves is really astounding.”

The siddur insert contains a version of Harachaman which blesses the queer community. This prayer, by a 22-year-old in Florida named Willow, is in honor of the victims of the Pulse massacre, as well as her mother:

“May the merciful one bless those whose love depends on nothing.

May they be renewed to choose life, and guard those who wear the garments of their soul.

In community, we are known to feed each other. This nourishment is our holy portion as humans, and is sanctified Jewishly in the consumption of bread.

The grains of wheat, barley, oats, spelt, and rye have sustained the Jewish people as primary foodstuffs for millenia. This miracle, of simply being able to see sprouts growing and eventually renewing our people, is potent.”

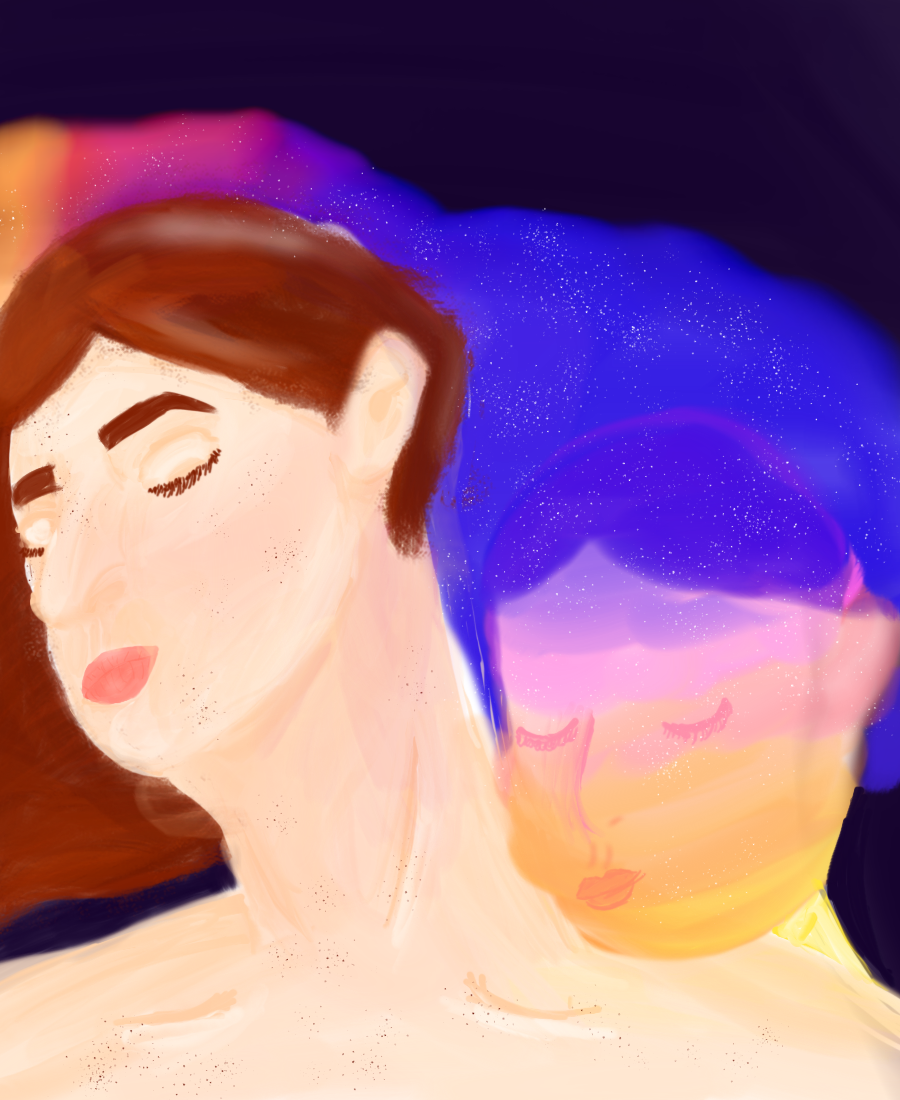

This visual piece was created by another young queer artist, and explores the notion of finding the strength to be happy as a queer person in a religious context.

This siddur is far from the first instance of queer young adult Jews creating their own religious spaces – crafting the kind of spirituality that they want to see in the world. SVARA, a queer yeshiva, recently released the Trans Halakha Project, which created and curated resources by and for trans Jews. In the process, they cultivated a radical and euphoric space for trans Jews to explore halakha. Though it is not exclusive to young adults, many contributors and participants are young adults creating a new era of queer and young adult lead religious communities.

“I could see this on my friend’s walls and in the pews of my synagogue back home,” Julia said. “I think that there has been this reflection in Jewish communities recently, to put their money where their mouth is when it comes to including queer people.”

With this siddur addition, LGBTQ+ young adult Jews get to truly share their voice in Jewish religious life.

Image credit: Eden Rosenfeld

Keshet’s siddur insert will be available in late September, 2023.