I’m hammering nails into my wall and the painting is not cooperating—no matter how many times I move it, it looks crooked. I rented it from my school’s art museum for the semester. Although the figures are blurry, I’ve learned that it’s three renditions of Masaccio’s The Tribute Money, a scene from the gospel of Matthew. Each is in its own panel against a dark background. They’re all connected, like the same thing is happening in different rooms of a lit up house.

As I decorate, I listen to one of those Spotify-created playlists. This one is called “Laurel Canyon Legends.” I take a step back, assess, adjust the painting again. Then, the singer mentions Jesus, and that’s when it hits me that what I’m doing may be a little strange. I run over to my phone. The song is called “Jesus in 3/4 Time.” I turn to the painting. Then, I notice the small statue on my bookshelf of the Virgin of Guadalupe. My Jesus Christ Superstar vinyl. Rosary beads I’d just bought.

Oh god. What is happening to me? I turn the music off.

I’m not a Christian. These moments scare me a bit, though. They’re lodged deep in my mind, but I rarely speak of them out loud—it’s like giving them power, making them true.

These are moments when I realize that, no matter how much I try to deny it, Catholicism is a part of my life. Lately, they’ve been harder to ignore.

I recently led a class session on patrilineality with Judaism Unbound, and chose an article written by another patrilineal Jew, “Embracing What It Means to Be Jewish and…”, for us to discuss. The author writes about the “immensity” of her mother’s sacrifice, and asserts that in order to truly honor her father and mother she can’t “reject half [her] own past.”

In class, we talked about the idea of being Jewish and something else as well. Many participants, like me, had tried to ignore their non-Jewish parentage for most of their lives. While in the past, this felt like something they had to overcome, they were now trying to embrace it.

Truthfully, I still feel uncomfortable with all of this. I mean, I’m just Jewish. As a patrilineal Jew, I’ve constantly had to defend my Jewishness to others. I’ve explained my dedication, how I had a Bat Mitzvah, go to Shabbat services, and don’t eat pork. I celebrate Christmas, but I was raised with that–not actively seeking it out. I don’t feel a connection to Christianity. It felt like everyone in my class was on a different level—they had already embraced this part of themselves, and moved on to feeling anger at Jewish institutions that had rejected them.

For so long, being Jewish has felt like it’s had to go alongside hating Christianity. But at the same time, I’m fascinated by Catholicism. I always have been, and I probably wouldn’t be if I didn’t have Catholic family. I don’t know how to reconcile these two ways of thinking.

When I took a class on Christian art history last fall, it was the first time I’d ever really let myself indulge in my interest. There, I read the Gospels. Here’s what I like about the Christian Bible: it has jokes. Early on, I call my mom to tell her about it. I ask her if she knows the part where Jesus is at a wedding and they run out of wine. “Of course I know,” she says.

Growing up, my mom went to a Catholic school and a Catholic college. I’ve heard some stories: the nuns, her teachers in grade school, were mean, she and her sister fought over their Confirmation name. I’ve seen her white, frilly First Communion dress, which hangs in her closet. Beyond that, I don’t know much about it. Unlike the mothers of some of my peers, mine calls herself a “recovering Catholic.” She hated Catholic school, and often felt estranged from her religion. But it’s still an important part of her life; it still informs her identity. By distancing myself from Christianity, I’ve distanced myself from a part of my mom’s life. I’m still trying to put together the pieces I’ve missed.

The Figurine

She stands on my shelf, wearing a long blue cloak. Jagged yellow beams frame her face. At her feet are pink clay flowers: as the legend goes, flowers spring up when her apparition appears. It was my mother’s as a child; she got it in her Christmas stocking. I’ve been able to justify my interest in the virgin of Guadalupe because it’s a way of connecting to my Mexican heritage. Unlike my Jewish background, I’ve felt estranged from my Mexican background for my entire life. I don’t know Spanish, I’ve never been to Mexico, the only food I can make is tacos. But the one way I do experience being Mexican is through Catholicism: tamales on Christmas eve, luminarios lining the sidewalk. Our Lady of Guadalupe, often more of a symbol of Mexican identity than of any religious belief.

I love that she’s become an icon in political movements. Most of all, though, I love all the little figurines. I tell people I’ve been collecting these little statues; by “collecting,” I mean I have this one and I’m going to get more. They’re on mantle pieces and altars, in gift shops and antique stores. I love all the knickknacks of Catholicism like how I love Judaica: candlesticks, spice boxes, jewelry. But with Catholicism, a religion so based around iconography, it seems you can never get enough small items with saints on them.

One afternoon in late December, I take down the rosary beads hanging from my rearview mirror. They’re hot pink and have become embarrassing. I bought them for three dollars at an antique store a few weeks before. “They’re camp,” I say to people who ask about them. “I’m Jewish.” They wouldn’t be camp if I was Christian, and displaying them earnestly. Still, though. I hide the beads in my glove compartment under some napkins.

In many ways, the kitsch has been a way in for me. It’s also the performance. The spectacle. I look at outfits from Heavenly Bodies, the Catholic-themed Met Gala, in awe of the silver and gold, Rihanna’s pope hat and bejeweled robes, Blake Lively’s long velvet gown and halo tiara. I sit in the pews with my mom at her college reunion mass, watching nuns carry an enormous, ornate golden cross to the front of the chapel. I look up at the high, arched ceiling, the stained glass windows. It’s a different world from my simple, mid-20th century synagogue. Catholics go here once a week? We watch as the rest of the room receives communion.

In his article “In Defense of Kitsch,” Ed Simon argues that the current understanding of kitsch as “low” is rooted in anti-Catholicism or, rather, an association of Catholic aesthetics with “bad” and Protestant art with “good.” He traces the roots of kitsch back to Catholicism, drawing parallels between the two. Traditional Catholic art, like kitsch, is “busy, frantic, colorful, ornate, gilded” while Protestantism values simplicity and minimalism. “There is,” he writes, “an unspoken set of theological-aesthetic commitments that have prejudiced the Anglo-American public into interpreting that which can be read as “Catholic” (or “ethnic”) as kitsch, and that which is Protestant—with its clean lines and unadornment—as the paragon of sensible good taste.”

This year, I wrote my Honors thesis on camp, kitsch’s more self aware cousin. If I’ve learned anything, it’s that taste isn’t natural; it always comes from somewhere. It feels a little silly to blame anything on anti-Catholicism in this time and place—at the same time, though, anything that feels as deeply ingrained as taste must have old, far reaching roots.

I always love to incorporate “bad taste” into my life; that which is tacky, gaudy, kitschy, like hot pink rosary beads or, one day, a shelf full of small statues of the Virgin Mary.

The Transfiguration

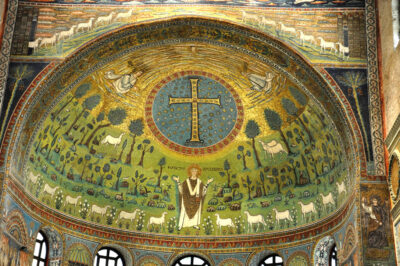

In our first month of classes, I’m assigned to compare two 6th century apse mosaics of the Transfiguration to one another. In one, Jesus levitates above three kneeling disciples. The background is a deep gold; it feels grandiose. The other shows a figure standing in a field, surrounded by sheep, trees, and sky. A small hand reaches down from the top of the picture, through the clouds where an enormous cross hangs. It feels simpler, older.

I spend a lot of time staring at the mosaics and listening to Sufjan Stevens’s Seven Swans, his most overtly religious album. The last song, “The Transfiguration,” has a simple melody. Like the mosaics, it feels distant, mystical.

I think it’s the distance that allows me to do this. Listening to Jewish songs while looking at art of the Hebrew Bible would feel corny. But there’s a mystique around Catholicism that still intrigues me. Maybe because of their insecurities about intermarriage, my parents were adamant about keeping it from my brother and me. What this did, though, was make us curious in a way we weren’t with Judaism. Judaism was safe, familiar, while Catholicism was forbidden and exciting. When we were little, we thought “Jesus” was a swear word because of how our parents acted when we said it. We’d whisper it to one another, secretly. “You said the G word!” “You said it first!”

There are many ways that having a non-Jewish parent can strengthen someone’s Jewish identity. Having non-Jewish family means that you have to be ready to explain certain traditions and their meaning. You have to think more consciously about which ones to incorporate into your own life. Sometimes, you learn about Judaism alongside your parent. I find, though, that conversations around interfaith families almost always center around this idea: justifying why this is ultimately good for people’s Jewish identities. What I’ve never considered is that maybe learning about Catholicism doesn’t serve my Jewish identity at all. That doesn’t mean I have to stop doing it, though. It serves my identity. It serves my intellectual interests, my aesthetic interests, my Mexican heritage. As I’ve learned that there are people who don’t think I’m Jewish and never will, as being Jewish has become less of a fixed, unchanging part of my identity, I’ve become more okay with this.

Saint Catherine

In my first week of Christian Art History, I go to my college’s art museum to write about ten pieces of biblical art. The museum has a bright red room that features much of its displayed Christian art. There’s a huge wooden cross hanging from one wall, and a sculpture of an emaciated Saint Sebastian in the center. I find a circular painting in the front, The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine. My mom took Catherine as her Confirmation name, after her mother, my grandmother. I’m named after her; she’s still alive. But who is Saint Catherine? What makes someone a saint?

As it turns out, St. Catherine was the daughter of the governor of Alexandria, and was devoted to study from a young age. She converted to Christianity at 14 when, supposedly, she saw a vision of the Virgin Mary and Jesus as a child. The Roman emperor summoned 50 pagan philosophers to dispute with her but, according to legend, she won the debate and was imprisoned, where doves tended to her wounds. She was sentenced to death on a spiked wheel, now known as a Catherine wheel, but, at her touch, it shattered. In the late Middle Ages she developed a medieval cult upon the supposed rediscovery of her body at Mount Sinai, apparently with hair still growing. She is the patron saint of young female students.

That’s all for me to find out later. Right now, I write: Bright reds and blues. Golden birds. Standing next to a taller woman and a baby. Ornate crowns. Are saints in the Bible? That’s enough. I keep looking at the painting.

Full image credits:

George Deem, “Masaccio, The Payment of the Tribute Money,” 1964, Gouache on paper (c) 2023 New Britain Museum of American Art / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Apse Mosaic: photographed at the basilica by Richard Stracke, shared under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license.

The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine: Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Ohio. Mrs. F.F. Prentiss Bequest, 1944.51