*This story has been updated to reflect new remarks made by Chris Steinberger, and now includes the use of the term Gedenkdienstleistende.

As a group of eighth-graders were led through the Holocaust exhibit at the Museum of Tolerance, they paused to learn about concentration camps and deportations. Their guide, a young Austrian, asked what may — at first — appear to be a simple question.

“The trains — how many seats do you think they had for people to sit down?” he asked.

“None” or “two” were some of the quiet responses from students.

The guide, Jonathan Rusche, proceeded to explain that cattle cars were used for deportations to concentration camps—trains which were not meant for humans.

The tour continued.

For 10 months, 20-year-old Rusche, from Salzburg, and 19-year-old Ferdinand Lieben-Seutter, from Vienna, are working at the museum as Austrian Holocaust Memorial Servants (Gedenkdiener). Originally developed in the early 1990s as an alternative to compulsory male conscription, the Austrian Holocaust Memorial Service (Gedenkdienst) has since been opened to all Austrians.

Fifty-five people worked as Gedenkdiener in 2019-2020, according to a 2019 report published by the Austrian Ministry of Social Affairs. Two associations, Verein Gedenkdienst–which also utilizes the term Memorial Service Worker (Gedenkdienstleistende)–and Austrian Service Abroad, receive funding from the ministry to send people around the world as Gedenkdiener, the latter offering placements in Los Angeles.

In May, an investigation by Austrian news magazine, Falter, reported on systemic intimidations and abuses of power by the chairman of Austrian Service Abroad, leading to his resignation a few days later. Funding from the ministry was frozen pending a review. Last month, the association stated that it is undergoing a restructuring process. Chris Steinberger, who previously carried out a memorial service with the other association—Verein Gedenkdienst—and who is a board member of the Austrian Union for Jewish Students, wrote in an emailed statement that especially when working with young people who are willingly partaking in memorial service work, structural abuses of power can never be tolerated. Verein Gedenkdienst is diligently working to avoid similar incidents in their own organization, added Steinberger.

Gedenkdiener typically find housing, obtain visas, and complete other major tasks for their service abroad independently, and receive some supporting documentation such as invitations or letters of confirmation. Those carrying out their service in Los Angeles are given about €650 each month from the association, and cover additional living expenses through means including financial support from family, scholarships or income saved up from jobs.

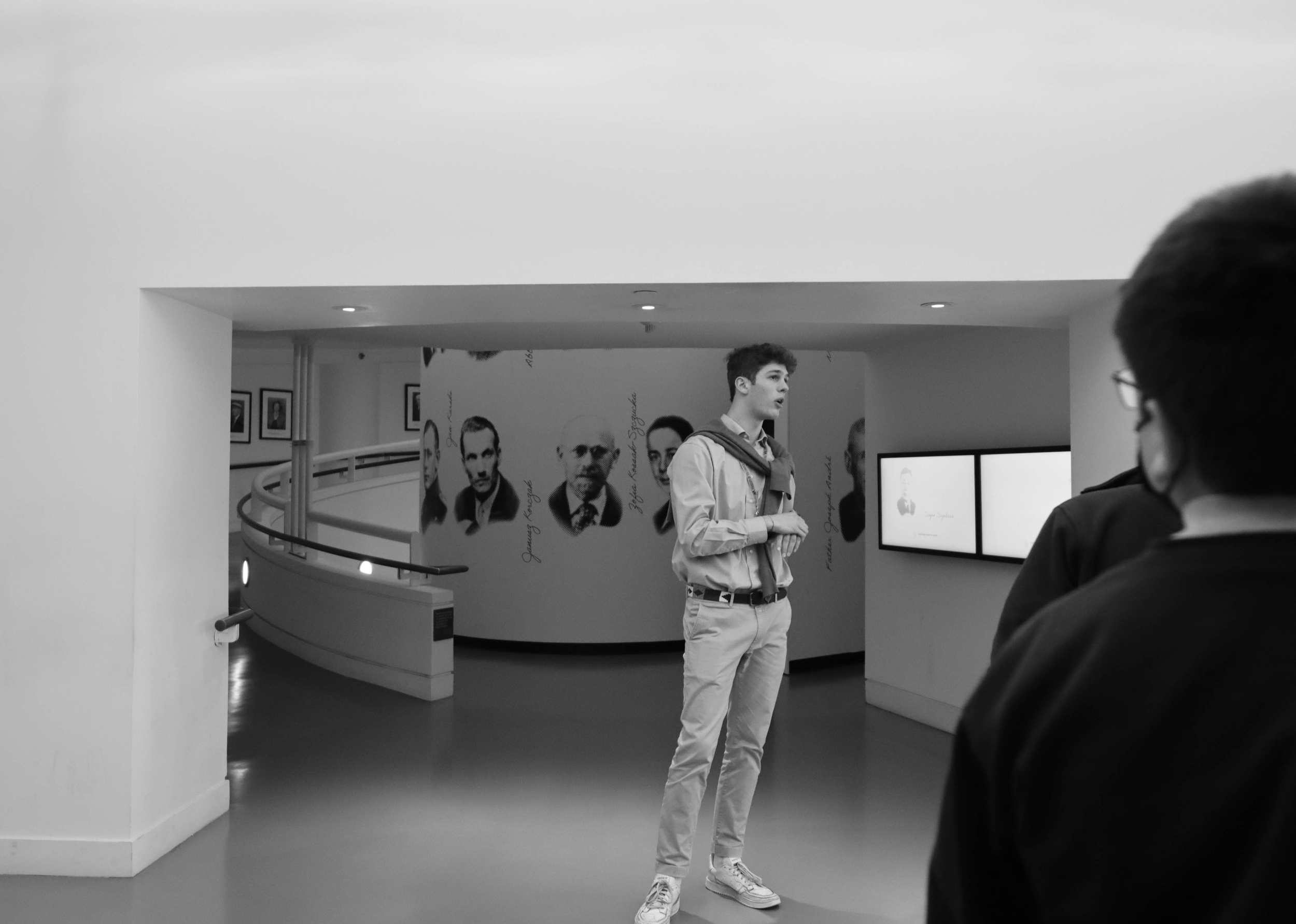

Jonathan Rusche (center right) speaks to a group of middle school students he is guiding through the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles in February 2023. “Every tour is different, but sometimes I talk about my program at the end to give them a perspective of choices and options,” said Rusche. “To give them some sort of contemporary perspective—look, that’s what Austrians are now doing and it’s not that long ago that Austrians did something very different. So there’s always the opportunity to change and to make change possible and you can do that as an individual, you don’t need a whole movement behind you. That’s one of the messages I always try to send in my tours.”

Ferdinand Lieben-Seutter (center) speaks to a group of middle school students at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles in February 2023. The memorial service program typically begins in early September and ends in late June, and Lieben-Seutter and his colleague Jonathan Rusche began leading tours in early November and late October, respectively. Every tour group is unique, they observed, and comes with varying behaviors, energy and interests. “Every tour I have, I’m learning new things—how to connect with the children [or] if someone’s not interested, how to make them interested,” said Lieben-Seutter. “You really learn every day.”

Jonathan Rusche (front) finishes leading a group of middle school students through the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles in February 2023. After guiding student groups in the mornings—starting in the Social Lab and continuing on to the Holocaust Exhibit—Rusche and Ferdinand Lieben-Seutter help with the day’s tasks, such as assisting with the preparation for events in the afternoons or evenings. They trained to be guides by shadowing other tours and attending trainings, which covered topics including the Holocaust, the Second World War, communication techniques and the history of civil rights.

The work performed by memorial servants abroad can vary depending on the institution in which they are placed.

In the Downtown area of Los Angeles, two other Austrian Holocaust memorial servants—Matthias Pail, from Graz, and Viktor Zlabinger, from Vienna—are based at the USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Visual History and Education, whose work focuses on the Holocaust and other genocides.

Matthias Pail (left) and Viktor Zlabinger (right) explain an immersive experience at the USC Shoah Foundation in January 2023 called The Last Goodbye. During this 17-minute virtual reality film, the viewer accompanies Holocaust survivor Pinchas Gutter to Majdanek, a concentration camp in German-occupied Poland. “So he went back there and you can go with him and he tells his life story—how they killed his sister, how he lost his parents and everything,” said Pail, who recalls when he first experienced it. “It was pretty mind-blowing for me when I first did it because I didn’t expect that.” Pail, who received a scholarship from Peace Bureau Graz (Friedensbüro Graz) to work as a Gedenkdiener, had always been interested in history and liked the idea of performing a memorial service. He learned about the program a few years ago, after his father saw on TV a video involving a Gedenkdiener working at Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. Knowing his son’s interest in history, suggested he consider the service.

Viktor Zlabinger (left) and Matthias Pail (right) explain some of their assignments at the USC Shoah Foundation in January 2023. Their 34-hour work weeks are occupied with long-term projects, smaller tasks, and staffing the front desk. One ongoing project they have been contributing research to is the Last Chance Testimony Collection Initiative. For this, they have been researching Jewish institutions in various U.S. cities so that the USC Shoah Foundation can contact Holocaust survivors who have not yet recorded testimony and may be interested in doing so now. “Sometimes, if some contemporary event happens, for example, Ben Ferencz receiving the Congressional Gold Medal, then it was my job to find an [interview] excerpt that should be released as part of a social media post,” said Zlabinger. He explained that Ferencz, a former prosecutor at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials, is someone that he admires and he has taken a great interest in Ferencz’s work and publications. They were also assigned to watch German-language testimonies, taking note of important moments—ranging from recollections of stealing food for other inmates to moving stories of family reunification—that could be used as stand-alone clips. Over time, this work could become emotionally heavy, said Pail. “If you watch testimonies for three weeks straight of people telling how their family got slaughtered, you kind of have to learn to leave things at work and not think about it before going to bed,” added Zlabinger. “That’s an ability you should have if you do this kind of work.”

Jonathan Rusche points to and discusses a display of a Nazi uniform with a group of middle school students he is guiding through the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles in February 2023. Before coming to LA, Rusche and Ferdinand Lieben-Seutter went on a four-hour tour of their own at Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. “Not everybody here has the chance to go to Poland and Eastern Europe and see these places for themselves, which is also a significant part of this program—we not only come with a certain knowledge but also experience and background,” said Rusche. “We’re not only Austrians but we actually are Austrians that critically try to educate ourselves about the Holocaust, that actually went on study trips to Poland and visited these places, that have historically also seen some roots in their family. My grandpa was in the Hitler Youth—now I’m doing a very different thing.”

Austria, which for many years saw itself as the first victim of the Nazis, both welcomed Hitler and participated in the Holocaust enthusiastically, explained Michael Berenbaum, a Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies at American Jewish University.

But this has changed dramatically, he added. Since the 1990s, there have been more attempts (in Austria and other countries) to honestly confront the legacy of Nazism and understand its implications.

Berenbaum, who is also the director of the Sigi Ziering Institute: Exploring the Ethical & Religious Implications of the Holocaust, had been involved in the development of museums such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Illinois Holocaust Museum and had come across Gedenkdiener during his time at such institutions.

“They come out with knowledge of the Holocaust and knowledge of the American community and knowledge of the American Jewish community, and they come out having served as teachers, docents and the like, with a good deal of skill,” he said. “They also have a special impact because precisely they overcome the stereotype of Germans and of Austrians that many visitors to a Holocaust museum have.”

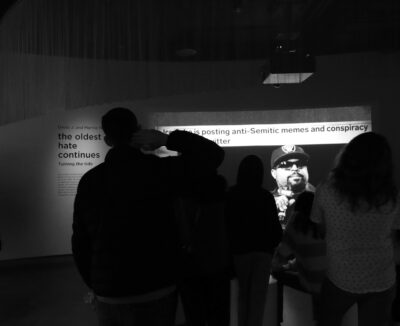

A group of middle school students, guided by Jonathan Rusche, watch a video titled ‘The Oldest Hate Continues’ in the Social Lab at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles in February 2023.

Ferdinand Lieben-Seutter speaks to a group of middle school students he is guiding through the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles in February 2023. Before leading them up the ramp lined with black-and-white portraits of Holocaust survivors and up to the ground floor to end the tour, he discussed with the group why they had come to the museum and what they could take away from their visit. Previously, he also mentioned to the group that half his ancestors were Nazis and half were Jewish. This is a personal detail he will sometimes bring up to leave an impression on students, but emphasized that the museum and subject matter should be the focus of each tour—not the Gedenkdiener themselves. Working at the museum and living in Los Angeles was a chance to participate in educating the next generation, and to experience life in a new country. “In Europe, I would say nowadays, the education about the Holocaust—at least in Germany and in Austria—is pretty high. You get to know it from a very early age because it is very important for us,” said Lieben-Seutter. “I wanted to experience the world and travel a bit and I thought to myself that Americans probably don’t get too much education about the history of Europe, and so I wanted to be a part of it, and the museum in particular, because the museum does not only educate the kids, but they also want them to be a part of the change, and that’s exactly what I want to do.”