“I don’t like him for obvious reasons,” my friend, a Jewish trombonist, told me. “But, for you, I will play Wagner because unfortunately I had to learn ‘The Ride’,” she said, agreeing to demonstrate the music of Richard Wagner for a lecture I was organizing.

“He just has so many bangers!” said another Jewish friend begrudgingly the same week, dismayed that we weren’t putting Ye West on the playlist for the rager that night.

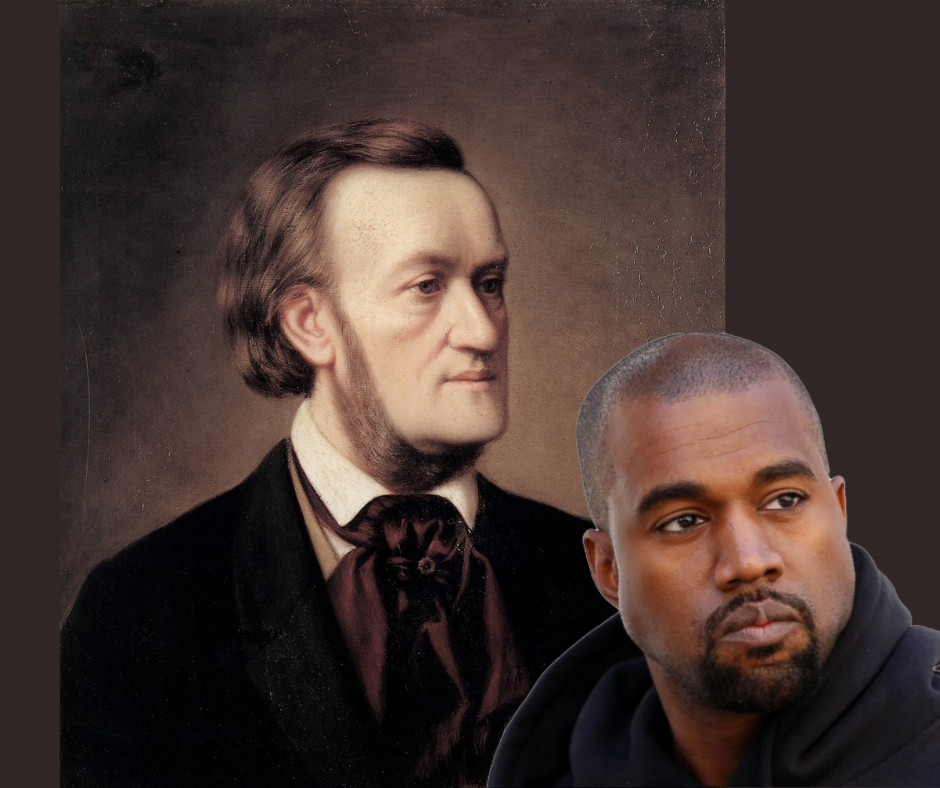

The romantic German composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883) and innovating hip-hop producer and rapper Ye West (1977-) are household names, but even if you don’t know their names, you’ve almost definitely heard their music. But for many, Jews especially, these two men are infamous because they share one thing in common — antisemitism. Dinner table discussions pondering whether we can or should play their music are ubiquitous.

I find myself in a continuous back and forth — between empathizing with fellow Jews who can’t abide listening to their songs and my own begrudging enjoyment of these two mens’ undeniably inventive, era-defining music. Part of me wants to lock their music away forever, knowing there is no shortage of amazing music out there written by non-antisemitic musicians. The other part of me rolls her eyes, kvetching. What’s next — chastising Jews who drive Ford cars?!

But after engaging in many of these debates, bigger questions emerged: Is it possible to separate the art from the artist, and go on enjoying each musician’s art in its own right? More pressingly, why are we so caught up in debates of musical “platforming” where “to play or not to play” is the ultimate question? Can we learn anything productive about antisemitism in pop culture through these discussions?

The histories of Ye and Wagner may just help us answer these questions. They both define the musical zeitgeists of their respective times and places in the world, but also attempt to normalize antisemitism.

Wagner and Ye: Background

Richard Wagner was born in 1813 to an ethnically German middle-class family living in the Jewish quarter of the German town of Leipzig in the Kingdom of Saxony. At the time, the many kingdoms of Central Europe were only just starting to merge together to become the German nation we know today.

He would become famous as a composer writing 13 operas in his life, including Der Ring des Nibelungen, what some considered the most ambitious work of music to date when it was finished, spanning at least 15 hours.

Wagner would move to the Bavarian city of Bayreuth later in life where he had an opera house built and founded the Bayreuth Festival, an annual celebration of his own music which continues to this day.

Nearly 100 years after Wagner’s death in 1883, Kanye “Ye” West was born in 1977 and grew up on the South Side of Chicago in a middle-class African American family. His mother was a college English professor, his father a photojournalist and former member of the Black Panthers.

Ye would become a break-out record producer and a rapper who released 10 studio albums and became the 3rd best-selling rapper of all time. He has delved into various other ventures including acting, venture capital, restaurants, music streaming and architecture. He made waves in the fashion world with his “Yeezy” shoes, collaborating with mammoth brands like Nike, Adidas, Louis Vuitton and GAP.

Ye also runs a gospel choir called the “Sunday Service Choir”, and was also involved in an 8-year long high-profile marriage with Kim Kardashian. In 2020, Ye even ran a third-party presidential bid receiving some 70,000 votes.

Artists to Antisemites

How did these two men with storied careers become infamous antisemites? Both men have a history of fiery political heterodoxy. Wagner befriended revolutionary anarchists like Mikhail Bakunin and even suffered a decade of exile from Germany after supporting left-wing German nationalists in the May Uprising. Ye too supported left-wing politics early on in his career stating that “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people,” in response to the Bush administration’s response to Hurricane Katrina.

Wagner released a now notorious essay in 1950 in the middle of his career entitled “Das Judenthum in der Musik” or “Jewishness in Music.” The essay, which was released in an arts journal, relies on the thesis that Jews will never make true German art. In Wagner’s mind, a Jewish person could only come to make true German art if they forgo their Jewish identity completely and assimilate into German society.

“To become man at once with us, however, means firstly for the Jew as much as ceasing to be Jew.”

– Richard Wagner

Ye, on the other hand, came out with an incendiary tweet in October 2022 where he stated that he would “go death con 3” on Jewish people, stating “you guys have toyed with me and tried to black ball anyone who opposes your agenda.” Ye’s antisemitism came after years of engagement with white supremacist messaging, donning a “white lives matter” shirt the week earlier. We might track it back to Ye’s growing interest in conservatism when he became a supporter of Donald Trump and befriended Candace Owens. Before this, Ye had donated exclusively to the Democratic Party.

German, Jew, German-Jew

Just as being white in modern America denotes one’s place atop a white supremacist racial hierarchy, so too, being ethnically German put you in the upper class of Wagner’s world. For many Jews, integration into society is seen as just as important as retaining markers of their Jewish identity. Full assimilation is not often not seen as a valid option. This was a problem for Wagner who believed that nothing less than complete assimilation would transform a Jew into a German — for Wagner, there is no German-Jew, there is only the Jew and the German.

In the case of Ye, James Baldwin’s 1967 essay “Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White.” may well help us understand Ye’s internalized antisemitism. In the few interviews he’s given since his October tweet, Ye has remarked about many poor dealings he’s had with Jewish people in his career, from those in the media to investors to physicians. In a conversation where Ye decries Jewish people in positions of power, Lex Fridman, the interviewer, pushed back. He emphasized that the individual in question was above all “just a person, not Jewish,” to which Ye replied in exasperation “But they are though, that’s the only thing, it just so happens that they are!”

For Ye, we can understand his antisemitic beliefs as deriving from a mix of anti-establishment sentiments feeding his sympathy for white supremacy, and his experiences of anti-Black racism. In another telling moment from Ye’s interview with Fridman, he complains about dealings with Bernard Arnault, a multi-billionaire CEO. Arnault is not Jewish and, knowing this, Ye instead decried him as a “French colonizer.” The common denominator between Arnault and the Jewish individuals Ye decried is their whiteness and power.

The “Snake Charmer” Narrative

We fear musicians like Ye and Wagner because we can’t reconcile the cognitive dissonance of enjoying the music of a person who has come to represent such a horrible value.

In our worst machinations, Ye and Wagner become snake charmers. Their music seems to coax and hypnotize the sleeping cobra of antisemitism into action.

We fear Ye and Wagner, knowing that the cultural power that they hold is now associated with antisemitism. Pieces of Wagner’s music continue to permeate our culture, from the wedding march from his opera Lohengrin (“Here Comes the Bride”) to the “Ride of the Valkyries” from his opera Die Walküre. The latter shows up everywhere from Looney Tunes to Apocalypse Now to the rom-com I watched last week, Crazy Rich Asians.

So too is Ye’s music and overall persona proved incredibly memeable. His bold and incisive TV appearance during Hurricane Katrina is as memorable as when he famously interrupted Taylor Swift’s acceptance speech at the 2009 VMAs, taking the mic from her to say “Imma let you finish,” before implying that Beyonce, not Swift, should’ve won the award in question.

Songs like “Lift Yourself,” with Ye’s out-of-pocket scatting “poopy-di scoop,” have found themselves at the center of internet meme culture. Ye and Jay-Z’s hit song “N*ggas in Paris” has become a common refrain in edgelord meme culture where the suggestive question “who was in Paris?” has become popular, even being invoked in the recent polarizing film about Black-Jewish relations,You People.

With such cultural ubiquity, Richard Wagner and Ye West can become icons for antisemites and fascists. Just the names themselves become dog whistles for far-right extremists.

In recent times, the “Wagner Group” which has been speculated to be named for the antisemitic composer, has become an infamous Russian nationalist paramilitary group with heavy links to white supremacist and Neo-Nazi communities. Recently, the group has been incredibly active in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

We already have seen a similar effect come with Ye West. Following his embrace of antisemitism, members of the American Neo-Nazi group the Goyim Defense League hung banners off of a Los Angeles highway stating “Honk if you know” and “Kanye is right about the Jews.”

Strategically Defanging

There is a large desire to pathologize antisemitism. At its core, antisemitism is an idea, a meme really. It can spread throughout populations in many forms — from myths to flippant jokes to physical threats. We might like to single out an antisemite as someone who is “sick in the head,” as in the case of Ye where attention is placed on his mental health diagnoses. Ultimately, however, this is wrongheaded and ableist, and doesn’t sufficiently explain such widespread hatred.

What we must recognize is that snake charming isn’t real. Actual snake charmings are performances starring tamed snakes who can’t hear music. So too, the cobra of antisemitism isn’t awoken by music, but by a musician’s charisma and widespread cultural reach. If we recognize this, we can better address and defang antisemitism when we see it.

We must push to separate art from the artist exactly because it gives false authority to Ye and Wagner who stand on the shoulders of giants as much as any creatives before or after them. Where would Ye be without Jay-Z and so many other hip-hop and soul artists before him? Where would Wagner be without Beethoven, Weber and the German romantic writers? Our society’s entrenched ideologies of artistic ownership deify these men into Gods conjuring their success out of thin air. The false narrative binds each man supernally to his music, which is exactly what gives them more power.

The question we must ask is whether the context of the music empowers antisemitism. Does Rihanna performing a Ye song she was featured on during the Super Bowl or an Israeli orchestra performing Wagner at all signify the growth or entrenchment of antisemitic ideology? Probably not. Does a group of men proudly calling themselves goyim who reference Ye, completely outside of his music? Definitely. An entire festival created by Wagner to celebrate Wagner should be implored to move away from their veneration of the antisemitic icon.

There is a double-edged quality of calling out antisemitism — we need to do it strategically and impactfully or we’re just giving it more fuel and attention than it deserves. If every enjoyer of Wagner or Ye’s music is an antisemite, what hope do we have?

Sometimes, it’s easy enough to make a tradeoff that can please the most people. Maybe there’s a good song by Kendrick or Travis Scott everyone likes. Why play Wagner’s “Here Comes the Bride,” when the German-Jewish composer Felix Mendelssohn has a wedding tune that is just as famous?