Food Rituals in a Thin-Obsessed World

The first time I “broke” Passover, I was ten years old.

The sun had set on the sixth day of the holiday, and my family was resting upstairs, innocent to what I was about to do. Shaking, I cowered in a dark corner of the dining room corner with a bag of cinnamon raisin bread that had gone overlooked. I stuffed pieces of fluffy bread into my mouth, testing what it would feel like to eat the forbidden thing. When the thrill subsided, I felt a paralyzing pain grip my body. I wasn’t afraid of being punished by God – an anxiety I would later hear about from Orthodox friends – I was ashamed of myself.

When I was a child, I adored Jewish food rituals. While it wasn’t the norm in my community, I vowed to keep kosher at age eight and chose to fast on Yom Kippur years before my Bat Mitzvah. I loved the thoughtfulness of these rituals. The attention to detail brought a divine presence to mundane moments of my days.

It wasn’t long before these holy practices were hijacked.

As an athletic teenager, I became immersed in “wellness culture,” which stamped morality into every ingredient I consumed. I blended an identical smoothie each morning, did intermittent fasting, and cut out bread-related items for years. “Fitspo” Instagram ruled my feed.

Soon, it became second nature to think of food in binaries: good versus bad, permitted versus forbidden, or innocent versus guilt-ridden. Holidays like Passover and Yom Kippur, with their religiously-sanctioned food restrictions, were frighteningly easy to observe; I was already fasting, and I didn’t eat bread anyway.

Thankfully, midway through college, I found the body liberation movement. Slowly, I started to break free from what I had been taught about bodies, food, and exercise. I learned about intuitive eating: listening to the body’s signals of hunger and fullness instead of imposing external rules. I realized that food is just food – nothing more, nothing less. I came to understand that there is nothing wrong with gaining weight, and that it is normal for bodies to change over time.

The body liberation movement has made strides to fight for bodies of all sizes, debunking the myth that “thinner is better”. Activists and researchers argue that body size does not indicate health, and that health does not determine one’s worth.

Even so, we all exist within a diet culture, where prioritization of thinness and weight loss is constant and pervasive.

Diet Culture: The Water We Swim In

Even if you don’t realize it, you’re swimming in a sea of diet culture.

Noom, a weight loss app currently worth 3.7 billion dollars, has been downloaded by 45 million users, who track their food intake and code food they eat as green, yellow or red (good, medium, and bad). Gwyneth Paltrow recently went viral with a video detailing her “wellness routine”: she drinks coffee instead of eating meals, fasts until 12pm, and drinks bone broth for lunch. This routine isn’t just common, it’s glorified: Influencers’ “what I eat in a day” TikTok videos break down every calorie they eat so their followers can follow suit.

Today, the weight loss industry is worth a whopping $470 billion. Every single day, we’re told that we should monitor the food we eat and consider the moral implications of every bite. With the insidiousness of diet culture, is it any wonder that anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness?

We must consider how these conditions affect our relationship to Jewish food rituals and restrictions.

When Diet Culture and Religious Food Rules Collide

It is with the backdrop of diet culture that we enter Passover: a holiday that tells a story of freedom and liberation.

Passover celebrates the ancient Israelites’ exodus from slavery in Mitzrayim (Egypt). As Jews today, we are commanded to see ourselves in their shoes.

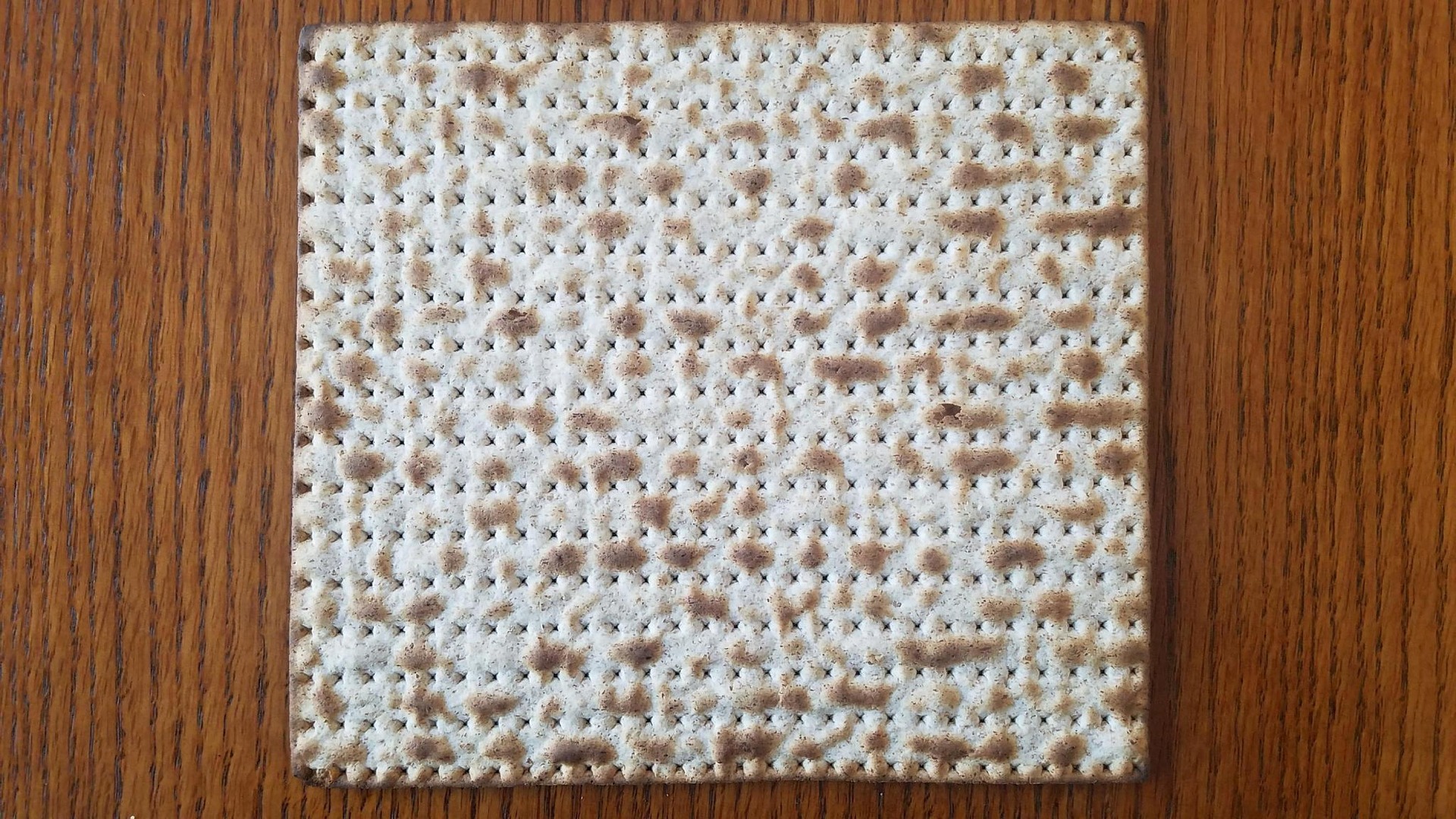

So, on Passover, we refrain from eating chametz (leavened bread and other related items) and we clean our houses meticulously to remove any traces of the substance. This is meant to be a holy action to connect us to our ancestors, reminding us of deliverance from Egypt – when we fled so fast we did not have time for bread to rise. For some, however, this ritual can evoke feelings of scarcity and fear, bringing them back to their own Mitzrayim.

“Carbs are the first and biggest thing I cut when I was restricting myself. They’re the most triggering thing to avoid,” one Jewish woman told me. “‘Bread equals evil’ is a scary thing for me to allow myself to think. Yom Kippur is only one day, but Pesach gives my brain time to settle into scary neural pathways. Basically, I’m scared for this week.”

I’ve felt these feelings too. In 2021, I wrote an article questioning whether it is possible to disentangle fasting from the connotations of weight loss and dieting, and maintain its religious value. Years later, I wanted to better understand how religious food rituals and restrictions impact those with – or in recovery from – eating disorders. On Instagram and Facebook, I asked people to share their experiences. Sadly, I found that I was far from alone.

“I used to relapse in my eating disorder almost every Passover,” someone said. “People would call Passover the ‘weight loss holiday,’” another wrote.

When cutting out food groups is the norm in our society, how does this affect our relationship to food rituals? For those whose minds have been enslaved by thoughts of food and bodies, how could food restriction remind us of liberation?

Jewish Approaches to Recovery

Jewish people with eating disorders have to navigate two strong, often competing conceptions of food: diet culture and Jewish culture. “Between Sabbath and celebrations, there is a preoccupation with food in Judaism,” says Sarah Bateman, a clinical social worker and therapist at The Renfrew Center for Eating Disorders.

The Renfrew Center hired Bateman specifically to work with Jewish patients. As the organization’s Jewish Community Liaison, she considers the unique issues in observance that can be triggering to them.

According to Bateman, Pesach (Passover) observance is filled with potential triggers. We cut out an entire food group for eight days. We engage in an intensive (and often stressful) cleaning process, removing all traces of chametz from our homes down to the tiniest crumbs. We reunite with family members who make comments on our bodies, especially if they’ve changed.

The Passover seder itself is filled with counting and portioning of ritual items. It can take hours to arrive at the meal. Those in recovery that have done so much work to undo the idea that certain foods are off-limits. These practices, Bateman says, can resurface dangerous disordered thoughts and behaviors.

Dr. Rachel Millner, a trauma-informed eating disorder therapist, also finds the confluence of food and religious observance to be triggering for her patients. When it comes to deciding whether to observe a Jewish food restriction, she says, “Either way, there’s guilt. There’s guilt if they observe the ritual, and there’s guilt if they don’t.”

Both therapists noted that shame discourages people from seeking help, particularly when they feel that by doing so, they are betraying their religious practices. The paralyzing shame that I felt while sneaking cinnamon bread as a child has followed many of us into adulthood.

A Mitzvah To Eat, a pluralistic group of Jewish educators and clergy, is working to change this trend. Those who need to follow mitzvot differently, they argue, deserve “respectful communal space and be seen as equal members of the Jewish community.” This group reminds us that according to the principle of pikuach nefesh, saving a life takes precedence over adhering to the law. Eating disorders are medical threats to mortality, so observing Jewish law is secondary to recovery.

Dr. Millner often recommends that clients struggling with guilt obtain permission from their rabbi to observe mitzvot differently. “God wants you to honor this holiday in a way that won’t increase sickness or harm,” she says.

Creative Interpretations

Bateman uses a two-pronged approach with her Jewish patients.

First, she takes a practical stance, asking her clients, “What about this ritual is triggering to you? How can we prepare for that in treatment?”

Secondly, she addresses the meaning behind the practice. “Why are you engaging in this ritual? What spiritual meaning do you hope to derive from this observance?” During Passover, she suggests infusing the holiday’s themes into ritual practices.

In “All Who Are Hungry,” an essay in Lilith Magazine, Ilana Kurshan connects the story of Passover to her suffering and eventual freedom from her eating disorder. The words of ha lachma anya (an invitation recited at the beginning of the seder), “Let all who are hungry come enter and eat”, are an empowering reminder of the possibility of food freedom. Meanwhile, they remind us to sit in empathy and take action, as there are many who, Kurshan says, “cannot or will not satisfy their hunger.”

Using the symbols of the seder plate, she evokes a dark past (the shank bone) but finds hope in the possibility of rebirth and renewal (the karpas). Reflecting on these connected themes can be useful to all of us – not just those in recovery.

Dr. Millner and her friends created a Body Trust Seder complete with a homemade haggadah that marks the journey from diet culture to fat liberation. The haggadah riffs on themes of Passover, and includes the Ten Plagues of Fad Diets and Sonya Renee Taylor’s “The Body Is Not An Apology”. “Why on this night do we eat whatever the hell we want?” the host asks. “Because we are free from diet culture.”

A Framework of Freedom

For our seders to improve, they must have a liberatory framework. For those in marginalized bodies, “It’s not just about not eating bread,” Dr. Millner says. Those in bigger bodies experience systemic discrimination, or fatphobia, in healthcare, the workplace, media, and more. Creating a seder free of weight stigma begins with thoughtfulness about every detail: the size of chairs, the accessibility of the space, and the way we speak about others’ bodies and our own.

This isn’t just a role for the host: Any guest at a seder can actively foster a more accepting environment for all who wish to celebrate. Simply refraining from commenting on another guest’s body or food consumption can go a long way.

This Pesach, I leave you with a blessing:

May we have clarity on the ways that diet culture shows up in our lives.

May we remember that no food is morally good or bad.

May we observe rituals in a way that supports our wellbeing, knowing that there is nothing to be ashamed of.

May we create a world where all bodies are valued and treated equally.