A Greek Jew who raised her children Christian. A lesbian who loved her husband dearly. A porn theater owner who’d managed to leave Athens on the eve of World War II. Nowhere could Chelly Wilson have been all of these things except for Times Square, New York love-it-so-much-you-want-to-say-it-again New York.

Wilson is the subject of “Queen of the Deuce,” a documentary that premiered on Friday at the film festival DOC NYC. The movie tells a story of an immigrant pulling herself up by the bootstraps to become lavishly wealthy and beloved, despite her multiple marginalized identities. While that narrative is true, anecdotes about her business dealings and how Wilson viewed money suggest that inspiration isn’t quite the right takeaway.

Wilson’s story exemplifies the mysterious familiarity that sometimes forms between the purely evil and the merely misfit, and the way repressive social systems can blur the line between them.

Born in Salonika in 1908, Wilson had a very religious Jewish upbringing. Her dad arranged her marriage, and she resented it. “Every kiss he put on my body, I wanted to kill him,” she said of her husband in an audio recording used in the film. “He was so repulsive to me, the son of a bitch.” After having two children, Wilson and her husband divorced. In 1939, as war broke out in Europe, Wilson left Greece — without her kids. She didn’t have custody over her son, and as for her daughter Paulette, Wilson decided to leave her with a non-Jewish woman, making her promise not to let anyone else take her.

In New York, Wilson sold hot dogs. In 1941, she remarried — to a man, of course — and managed not to kill him. “It was nice,” Wilson said of her marriage with Jewish projectionist Rex Wilson. “He provided me with cigarettes.” She’d later have relationships with two women who stayed in her apartment. Wilson wasn’t involved in porn yet, but she owned a theater where she showed Greek films. As business went well, Wilson raised money to send the Greek army to support their anti-Nazi effort. She also helped Greek immigrants obtain legal status in the U.S.

Salonika, which had such a large Jewish population it was nicknamed “la madre de Israel,” was taken by the Nazis in April 1941. The Jewish population in Wilson’s hometown was almost entirely annihilated, but her children survived — her son Dino because he’d made it to Mandatory Palestine, Paulette because her mom had sent her to live among Gentiles.

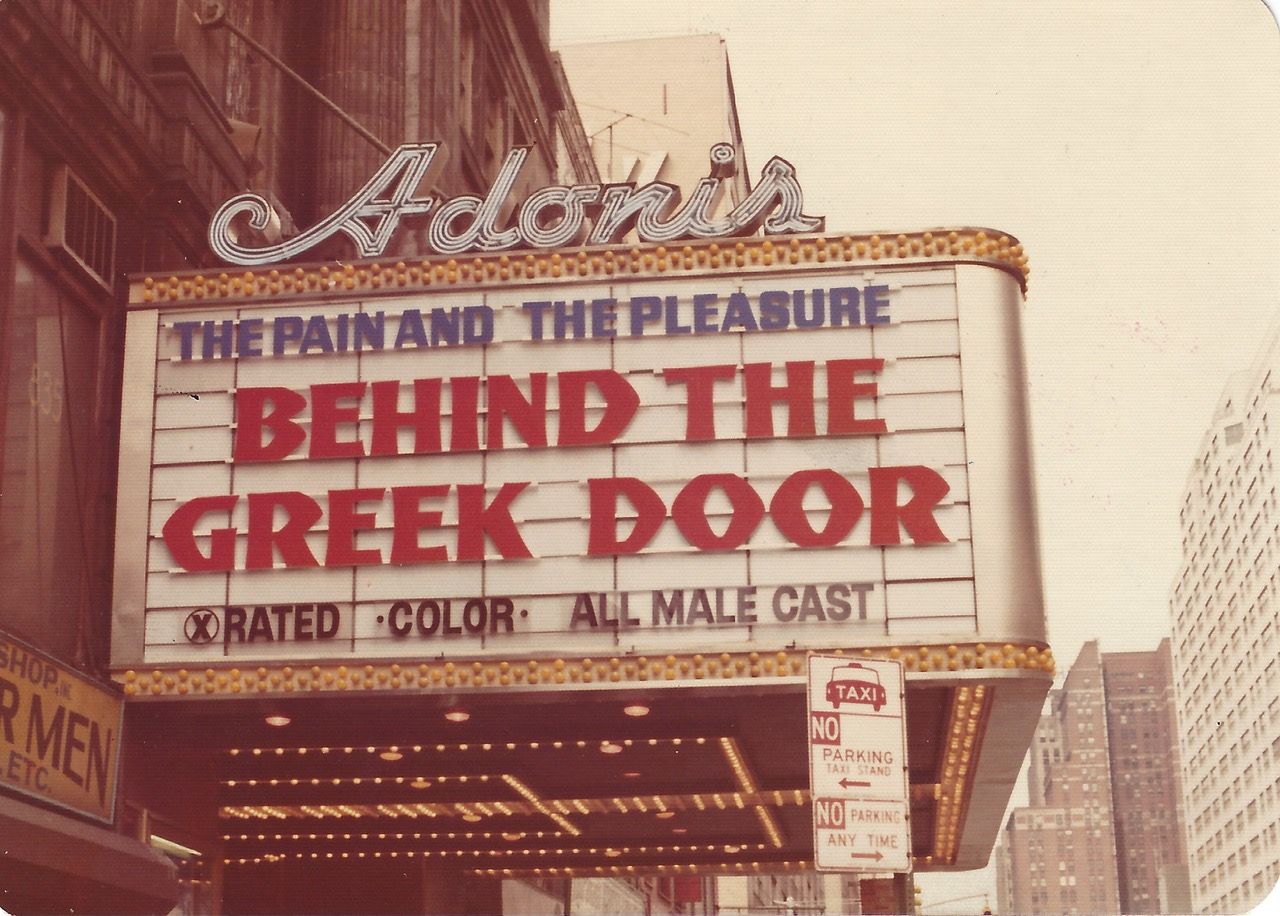

Meanwhile, as the market for Greek films declined, Wilson started showing porn and soon owned several theaters. In Times Square, in midtown Manhattan, a new world of smut had emerged, thanks to thirsty G.I.s, evolving laws, white flight and the changing character of the city. The neighborhood, nicknamed “the Deuce,” would soon be complete with sex workers, adult bookstores, illicit massage parlors and peepshows. While politicians tried to use gentrification to reduce the area’s violent crimes and put what they viewed as depravity to an end, Wilson stuck it out until the ‘90s.

In the ‘80s, a debate played out on the Deuce’s streets, with activist Andrea Dworkin and others arguing that porn was inherently anti-feminist. Wilson, for her part, didn’t bother with such questions.

“She never had any compunctions about any of that. Couldn’t care less about the content,” said Wilson’s son-in-law Don Walters, who was also involved in film on the Deuce.

Actually, Wilson did care about content; she wanted whatever content was most profitable. Articles attest that she asked filmmakers for more sexual content and hardcore close-ups, knowing they would sell; a 1971 Variety article says she ordered cuts to films to avoid hassles with the district attorney. And while Wilson was one of the first people to bring gay porn into New York City, it might have been more of a financial calculation than a brave social stance; the city had a large untapped market of gay porn consumers, whom Wilson charged more than she charged audiences for straight films.

“I think she loved the deal and making the deal more than she ever loved what the deal finally led to,” Walters said.

The qualities Wilson admired in her fellow deal-makers could get her into trouble. Her associates in the documentary say that at the time, it would’ve been practically impossible for someone to work on the Deuce without crossing paths with the mafia. Mobsters dominated the scene; because of the scale of their operation and their willingness to use violent tactics, they were able to turn a profit despite police raids and other challenges inherent in the legally iffy world of porn and sex work. While it’s unclear what associations Wilson might have had with organized crime, in the documentary, her grandson describes her as being “like a mafia queen.”

“She loved people who knew how to talk and get things done and sneak behind things and go around things. She just adored people like that,” Walters said. “And unfortunately, she got involved with a few of them and got taken a bit from time to time, because they were good at it.”

John Colasanti, who worked for Show World Center, a Times Square sex emporium, says that when he met Wilson, they hit it off — possibly because she liked being admired. “I think perhaps that’s why she took a liking to me — because she saw the admiration I had on my face when I would speak to her,” Colasanti said in the film.

Wilson was also accused of cheating people out of their money.

“We had to deal with her, but she was a little cunt,” said pornographic filmmaker Phil Prince in an interview with The Rialto Report, a Deuce-themed website run by amateur historians. “She was cheap, man. No one liked her.”

Film producer Arthur Morowitz said that in 1965, she took advantage of his inexperience to charge him a very high price to advertise the film he’d invested in. It was “a very typical Chelly kind of deal,” Morowitz said in the documentary.

They say all’s fair in love and war — did Wilson believe the same to be true in business? Maybe Morowitz should’ve researched reasonable advertising costs. After all, porn was a business for people who could handle it. In other words, one can imagine how someone in Wilson’s position might’ve justified her approach to business.

The documentary — which is mostly interesting and insightful — has a strange final scene featuring Wilson’s grandson, filmmaker David Bourla, who says his grandmother’s story inspires him. “If you’re not here to create something or to give someone else escapism or have a message or do something, then what are you doing?” he says. It’s a strange note to end on, since all available evidence suggests that Wilson didn’t care about creating anything, at least not anything artistic.

A New York Post article says Wilson “embodied the American dream.” But if realizing this dream means treating business like a game that must be won at all costs, what is that achievement really worth? Maybe, when a person doesn’t fit in somewhere, they hook up with others who don’t fit in either, not bothering to measure which parts of them don’t fit into what and why. Born 90 years later, would Wilson have had different values? Would she have waved from a float at her local dyke march, dissing the patriarchy and white Christian nationalists at every turn, aligning herself with pride and liberation rather than with mafiosos and other ill-defined troublemakers, whose trouble could be good or bad depending which way the wind blew?

The film can’t answer these questions, and neither can any journalist. But it’s worth wondering what happens when a person is placed in the position of needing to always justify themselves. They just might learn to justify other things, too.

“Queen Of The Deuce” is showing online now through November 27th at DOC NYC. You can buy tickets and watch the documentary here. Featured image of the Adonis Theatre marquee. From “Queen of the Deuce,” directed by Valerie Kontakos. Courtesy of the Wilson Family.