Demons. Jews in the Mountain West. The moon. These are just some of the subjects explored in the wide-ranging world of Jewish zines.

Last month, about 100 Jewish creators from around the world logged onto Zoom on August 9th as part of Jewish Zine Fest, an international celebration of the Jewish underground press. Over the next three days, the group held lively discussions on creating connections across the Jewish diaspora and using zines in rituals, and even hosted a virtual zine party where creators read their zines aloud. Some creators met in person at about 10 pop-up events, including gatherings in Central Park, Western Massachusetts, Portland, and even Canada, to make zines in person.

The festival –––which is the first of its kind to the creator’s knowledge––was organized by Jewish Zine Archive founder and archivist Chava Shapiro, along with creatives Eva Peskin, Lilli Sher, and Coco Rosenberg. The group created the festival as a way to bring together zine makers across the globe.

“A zine is an informational pamphlet or small booklet that traditionally was used for political education or distributing artistic content in a way that didn’t necessarily flow through other more formal modes of information distribution,” Rosenberg explained.

The Jewish zine archive is devoted to chronicling all the zines that are, well, Jewish. But even Jewish zines are not all alike.

“They can take any shape, they can take many different forms, but what’s consistent is that they have some relation to a vision of transmission that’s beyond conventional publishing apparatuses,” Peskin said.

The unconventionality of zines also allows for the spread of nontraditional Jewish ideals.

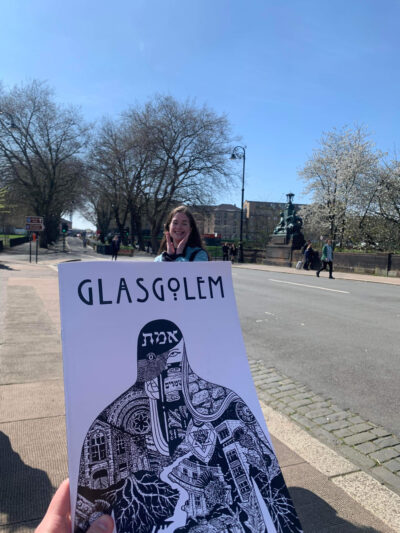

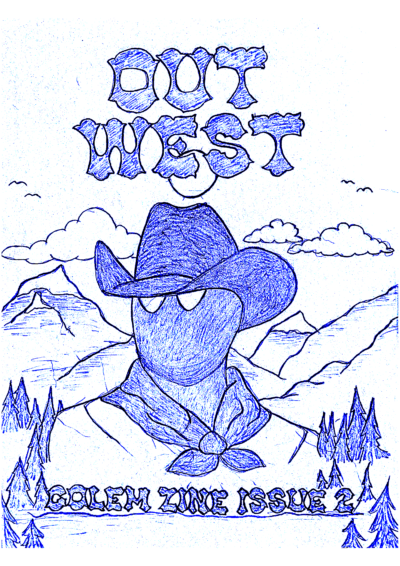

“A lot of the zines I engage with are anti-Zionist or queer or feminist led and there’s not a lot of space for that in mainstream written Jewish literary circles,” said virtual panelist Julia Hegele, creator of Golem Zine. “Zines are the grassroots alternative to that. We get to see reflected in them this really vibrant and ever-present community of Jews that really are fighting for different values than what mainstream Judaism is backing. It’s refreshing and it’s healthy.”

Hegele, who has previously written for New Voices Magazine, spoke with a passion for independent publishing, especially among young and alternative Jewish diasporic voices. Hegele’s own Golem Zine seeks to undo the idea of Jews only living in very specific parts of the world and bring awareness to the diaspora outside of hot-ticket areas such as Glasglow and the Mountain West. During the festival, she found it valuable to talk to fellow zine-makers from around the globe.

While zines are having a renaissance right now, they’re not new. For decades, zines have been used for everything from political education to punk fandom. They’ve also been a long-time part of Jewish tradition: Shapiro likes to say Rashi––the eleventh-century rabbi known for his comprehensive commentary on the Torah––was “the original zinester.”

“He would handwrite little pamphlets on pieces of paper, with his Torah commentary, and make a bunch of copies of them and give them to everyone who would take one. That’s so any Jewish zinester I know,” Shapiro said.

Many of the organizers and panelists at the event agreed that there is something inherently Jewish about zines and zine making.

“There’s a thing in Jewish culture that everyone has their own take on a story. You have your drash on something and zines to me are little drashes, whatever you feel like drashing,” Peskin said, alluding to the Jewish tradition of commenting on Torah passages through Talmud, conversation, and other writings.

For Rosenberg, zines and Judaism are both media which question the world around them. “To grapple with questions of the world is a very Jewish practice and to put it out there and share with others to start those conversations so others can respond just feels really Jewish to me,” they said.

Shapiro explained that zine culture’s lack of rigidity allows for ample creativity and expression of Judaism.

“That’s when Judaism and Jewishness are at their richest,” they said. “We can get it out of bounds and be experimental and creative and innovative and tapping into those foundational aspects of Rabbinic Judaism’s innovation and reinvention. And it makes sense that a format that allows for more self expression and less bounds and rules sits well with this other thing happening among Jews and Jewish life and Jewish practice.”

The festival, Hegele emphasized, played a huge role in encouraging creativity in zines.

“As a creative, it blew my mind because I got to speak to so many other creatives and have such great chats,” she said. “Some of the ideas you read in Jewish zines are things we all know but may be afraid to say or are in a community where it’s not comfortable to say. If you hear another Jew on another side of the world have the same ideas as you do, that’s grounds for collaboration, for organization, for movement-making.”

For independent zine-makers, international events like the Jewish Zine Fest provide much-needed opportunities to connect with creatives who may often feel isolated and far apart.

“It felt really special to know that there are all these seeds scattered all over of people thinking and creating and convening around pretty deep and tender topics but also fun and playful invitations to make zines,” Peskin said.

The community of zine-makers extends beyond the festival, with new events catalyzed by their convening this summer. Several zine-makers highlighted how the event inspired various group chats to continue conversations that began with the festival. The group is still thriving, which Rosenberg says is important for their own work as a zinester.

And, Shapiro emphasizes, everyone is welcome.

“Anybody can make a zine and anybody can be a Jew that can make a zine,” Shapiro said. “What’s exciting to me about creating a collection of those things is that it’s creating an archive that can be looked back on in the future, and is capturing something about Jewishness that’s a lot less likely to make it in the official history record.”