If you’re a Jewish student on a small or significantly non-Jewish campus, feeling overlooked from the priorities of school administration probably sounds familiar. In fact, Jewish students have fought for recognition and resources for a long time: the story of independent alternative Jewish student life is more colorful than most students know today.

“The Jewish student groups had been stuck in literally the basement of one of the buildings, of the worst space on campus,” said Mik Moore, one of the founding members of Ra’ashan, an independent Jewish cultural journal founded at Vassar in the mid-1990s. After years of neglect by their school’s administration, that frustration turned into action: Jewish students protested at Vassar, drawing attention to the lack of student programming and support for Jewish students – and successfully demanded a larger gathering space.

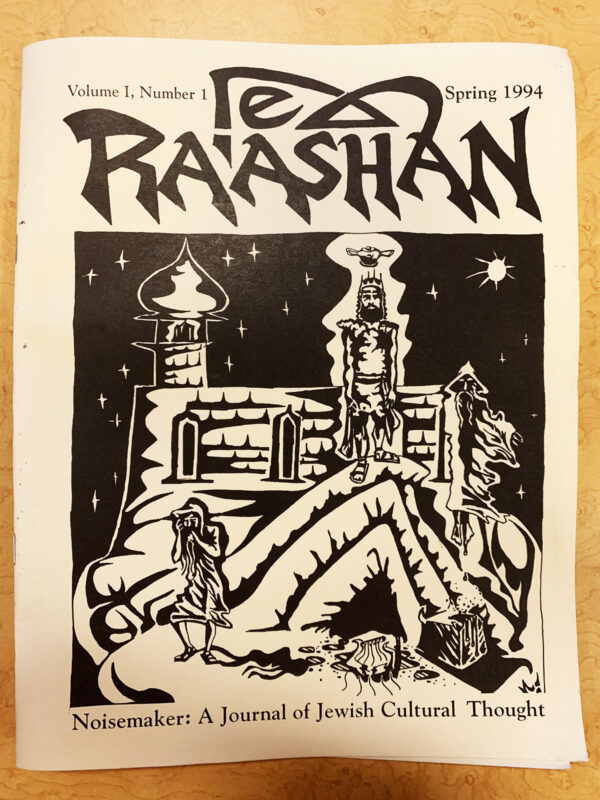

Without adequate Jewish student programming, or even a Hillel organization, Moore and his peers decided to create Ra’ashan, a student-run journal that also served as an alternative community to the already established Jewish student life on campus in 1994. When Ra’ashan sought support for their fledgling project, they received funding from the North American Jewish Students Appeal (NAJSA), which is when Moore first discovered that his own independent student group was one of many in a long, forgotten history of independent Jewish student groups organizing on campuses across the nation.

“In addition to funding these microgrants to tiny campus papers like mine, [NAJSA] was also the funding arm of independent Jewish student organizations,” Moore said. “As I got to know this space better, I realized that there was a long history of [NAJSA]… and independent Jewish student-led organizations, campaigns, and publications that were part of this moment of student leadership.”

NAJSA’s story began a few decades earlier in 1969, during an era of incredibly dynamic student life across the country, coinciding with the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War, and other major political events. Jewish student leaders and organizers were mobilizing nationwide for a number of causes, along with the rest of the “New Left”. Within the Jewish community, student activists demanded more funding for education and independent groups. Their concerns were simple: The Jewish student activist movement believed there were not enough resources and funding for the evolving demographic of Jewish youth that was becoming increasingly radicalized, and decided it was time to rebuild the Jewish institution.

In May of 1969, Jewish student activists conferred at the World Union of Jewish Students (WUJS) to discuss the issues concerning the state of Judaism among American youth. From this conference arose the North American Jewish Students Network, a communications, information and resource arm of the WUJS. Following the conference and through the Network, Jewish students and other Jewish young adults coordinated a series of sit-ins and protests to disrupt the Council of Jewish Federations and Welfare Fund’s General Assembly in Boston from November 12-18, 1969, coinciding with the 75th Anniversary of the founding of the American Federation movement. This protest built momentum as these students worked to be recognized in the Jewish world as a legitimate and equitable form of Jewish student life, loudly interrupting business as usual for American Jewish Federations. Within the year, having secured new funding for a growing movement of independent Jewish student activism, NAJSA was born.

Among these radical Jewish activists was Rabbi Hillel Levine, a Ph.D. Candidate at the Department of Social Relations at Harvard and a Graduate of the Rabbinical College at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTS). Levine urged for the federations to no longer be run by “a few generous men or the patrons of particular projects,” as he wrote in his address to the Council of Jewish Federations and Welfare Funds in Boston. “We want a change of the order of allocations and we want more equitable representation in decision making.”

Rabbi Levine was an advocate for the rights of Soviet Jews, taking action and even risking his life to defend them at a time when the Federation was silent. In fact, the American movement behind the liberation of Soviet Jews was largely spearheaded by students and young rabbis. Levine was one of few American Jews who participated in a wide array of historical actions; he volunteered to defend Israel in the Six Day War of 1967, defended Soviet Jewry and Ethiopian Jews, and worked domestically to fight for Civil Rights. He worked closely with people like Elie Weisel and Abraham Joshua Heschel, a prominent Rabbi and Civil Rights Activist who worked closely with Martin Luther King Jr.

Many of the actions of NAJSA were inspired by the Black Power movement, which centered the idea that strong ethnic identification was not just good, but essential to their movement. “[The Civil Rights Movement] had a big impact on me. I spent five years studying with Heschel and trying to understand Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement from the perspective of the Torah,” Levine said.

Rabbi Levine’s actions were not all positively received. “At the Seminary, they often looked askance at my volunteering to defend Israel during the Six-Day War, at my efforts on behalf of the safety and freedom of Soviet Jewry, on behalf of Ethiopian Jews, and of global Civil Rights,” he recalled. As a student studying with prominent psychologist Erik Erikson, he was threatened with expulsion for leading support to defend Soviet Jews. “They wanted to throw me out because they saw it as acting out, rather than my commitment to Torah and commitment to values,” he said. Despite resistance, Levine and his colleagues saw the advancement of NAJSA, and so began the journey of independent Jewish student organizing.

In November 1969, NAJSA successfully acquired funding for the programs and projects stated in their mission for adequate and self-governed Jewish education and culture. By the 1970’s, a new era of independent Jewish student life began to flourish. “There was a sense, an expectation, that student life for Jews on campus was run by Jewish students,” said Moore.

NAJSA’s new resources for radical Jewish student projects catalyzed and supported many groups and movements. NAJSA primarily supported six independent member organizations: The Jewish Student Press Service, the North American Jewish Students Network, RESPONSE Magazine, Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, Yavneh, and Yugntruf. In 1971, supported by NAJSA, the North American Jewish Students Network published “A Guide to Jewish Student Groups,” to spread the word about all the independent organizations flourishing across the country.

“These six independent national Jewish student groups have broken away from the historic trend of the Jewish community which has been to react to crisis situations,” wrote Susan Dessel, the first woman to serve as the Executive Director of NAJSA in 1975, in her open letter to DIALOGUE, a private forum that sought to influence Jewish unity and communal experiences. “Instead, they fight, in addition to the daily problems of any office, empty bank accounts, the fear of change held by many in the community who sit in positions of ‘influence and power.’”

A constituent organization of NAJSA, The Jewish Student Press Service (JSPS) became a wire service that connected and provided content for the various independent Jewish magazines and newspapers (such as “Attah” Student Newspaper from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, “Hayom” Paper out of Philly, and many others) proliferating on college campuses across the country – and eventually began publishing New Voices Magazine in 1991. Mik Moore of Ra’ashan himself went on to serve as the Executive Director of JSPS, working as the Editor of New Voices from 1996 until 1998, part of a lineage of many recently-graduated Jewish campus activists-turned-editors. Today, JSPS remains one of the last living vestiges of NAJSA’s student empowerment legacy.

Just over a decade after its founding, one of the students who worked on the NAJSA funding committee was Rabbi Jill Jacobs, the current CEO of T’ruah, who at the time was an undergraduate student at Columbia University. Jacobs became one of the original members of Lights in Action (LIA), another contemporary and NAJSA-funded Jewish student group dissatisfied with the state of Jewish student life on campus. “There was not a lot of deep learning in the non-religious Jewish organizations,” said Rabbi Jill Jacobs. “So part of the argument for starting LIA was that we needed serious engagement with Judaism. It was very much students empowering other students to [engage with] Judaism.”

LIA was founded in 1991, two years before Rabbi Jacobs came to Columbia, in response to an invitation from the University to Leonard Jeffries, a professor from the City College of New York, to come speak on campus. Earlier that year, Jeffries had advanced antisemitic rhetoric, igniting action from both the Jewish Student Union (JSU), along with the Lesbian Bisexual Gay Coalition (LBGC). Despite plans made to protest the event, students decided to further turn their anger into a new project, forming Lights in Action. “It was totally independent, student-run, with the theory of ‘students should do for students.’ I’m pretty sure we didn’t know the term community organizing at the time, but that was the philosophy, we’re organizing for our own community,” said Jacobs.

Their first course of action was to create and distribute Jewish materials, consisting of booklets of Torah excerpts, comics, and deep reflection questions, mailed to nearly 100,000 Jewish students a few times a year. LIA also hosted conferences and Shabbat services for groups of students, generating ideas and sponsoring communities that were neglected by Hillel, such as Jewish activists, Jewish artists, interfaith Jews, and queer Jews, who at the time were fighting to become members of their Jewish student organizations. “It was extremely radical that a Gay Jewish organization could be in their Hillel or Jewish student organization, and Hillel International was not touching any of that,” Jacobs said.

Soon after LIA came other NAJSA-funded organizations like “The Bayit Project,” a Jewish communal housing project that arose across 23 universities including UC Berkeley and University of Pittsburgh, and more groups, including Youth for Yiddish (YUGNTRUF), Yavneh (National Religious Jewish Students Association), and the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry (SSSJ).

But after two decades, NAJSA’s incredibly successful run was clobbered by major resistance. At around the time when Ra’ashan was seeking funding from the NAJSA in the early 1990s, Jewish college students became a new priority of Jewish communal institutions after a 1991 study revealed that the intermarriage rate amongst Jewish students had risen to 52%. Concerned about the intermarriage rates in the Jewish community and the political radicalization of the Jewish community in the 1980s, the Council of Jewish Federations and Welfare Fund decided that it was worth their time and investments to support Jewish student life – using a top-down approach. “In order for Hillel to get the level of funding it wanted from the Federation, which was a lot of money, they needed to be the only place the Federation was funding, and the Federation was still funding NAJSA,” said Mik Moore. “So Hillel basically convinced the Federation to eliminate NAJSA, and instead put all of its money into Hillel.”

The once-thriving independent Jewish student life of the NAJSA-era quickly folded to the Hillel campus conglomerate, to the point of almost non-existence. When the early 2000s arrived, the Jewish Student Press Service and Lights in Action were the last ones standing, NAJSA had completely collapsed, and LIA became the United States representative to WUJS. With so few sources of independent Jewish campus life, the established Jewish community had already begun to forget the impact NAJSA had already had. “I remember at WUJS, [someone] said [Jewish students] are the future, and everybody stood up and walked out,” Rabbi Jill Jacobs said. “We were like, ‘We’re not the future. We’re here right now.’”

This was not the first and certainly not the last example of radical Jewish student voices being silenced by the establishment; even giants like Chabad are on the outskirts of this centralized Jewish funding. This is why today, Hillel has become nearly synonymous with the image of Jewish student life on college campuses, despite a history and legacy of independent Jewish groups across the country yearning for an alternative, independent, student-led Jewish community, free from donor-influenced political redlines.

But Judaism is not a monolith. So even without NAJSA, where are all today’s young Jews who do not feel represented by Hillel?

My campus Hillel was one of the first stops I made when I came to Clark University in August of 2018. I was so concerned about seeking a community of Jews at my new home away from home, I thought Hillel was the only option for me, even though I knew that the organization continues to vehemently represent a particular view of Judaism that has ostracized queer Jews, Jews of Color, non-Zionist Jews, and more.

On my college campus, there is a independent Jewish community called, JGAF, which stands for “Jews Givin’ a F*ck.” JGAF is a student-led, non-hierarchical religious, spiritual and cultural community that is committed to the liberation of Jews and non-Jews of intersecting marginalized identities. Through art, conversations, and organizing, JGAF emphasizes the idea of collective liberation, meaning that the fight for liberation for one marginalized group is inherently in solidarity with another, a message similar to that of Rabbi Hillel Levine back in the 60’s.

Yonah, a Mizrahi Jewish third-year student from Los Angeles who requested to use only his first name, said he didn’t feel welcome in Jewish establishment spaces. “Most Jewish spaces aren’t inclusive of LGBTQ Jews and Jews of Color such as myself,” he remarked. “At Hillel, I felt like an outsider because no one believed I was Jewish. [At JGAF] we hold events and engage in Melodies/prayers that reflect non-Ashkenazi culture and history.”

Like many Jews who have experienced alienation in traditional American Jewish organizations, coming to terms with the norms of those spaces I was entering usually meant either silencing myself or accepting that I would be othered if I didn’t. Nati Botero, a Latine Jewish sophomore from Miami, Florida and Madrid, Spain, explained this feeling of othering. “Traditional Jewish environments that I grew up in felt restricting for my self-discovery, especially as a queer, non-binary, Latine Jew,” they said. “I’m really grateful to have a space like JGAF, where everyone gets to explore their Jewish identity, seeing how it intersects with other identities.”

NAJSA paved the way for organizations like Judaism On Our Own Terms (JOOOT), previously known as Open Hillel, independently founded to bridge independent campus Jewish organizations together to create a wider, national movement, committed to promoting student self-governance and radical inclusivity. Today, JOOOT is recognized on 13 college campuses, including my very own, Clark University in Worcester, MA.

According to their founding principles, JOOOT groups are united in their mission to foster student-run, democratically administered, inclusive Jewish communities on campuses:

- Establish and support democratically-run Jewish campus organizations by and for students within which students have the primary authority to determine leadership structure, and collectively decide rules, programming, and organizational mission.

- Resolve never to jeopardize student needs in the name of donors’ political interests.

- Protect and empower Jewish students facing increasingly common attempts to silence their voices, perspectives, and political opinions — especially regarding Israel/Palestine — by working against attempts to intimidate students.

- Embrace students’ diverse Jewish identities and understandings of “being Jewish” without political litmus tests or assumptions about sexual orientation, gender identity, race, or class.

- Create vibrant Jewish spaces for ritual, discourse, and engagement with social justice issues, along with mechanisms for these spaces to share resources and support one another.

JGAF, now an official member organization of JOOOT, was formed deliberately as an alternative to Hillel, because many Jews on campus felt excluded, unwelcome, or marginalized by Clark Hillel and Hillel International.

Aaron Kirshenbaum, a Ashkenazi Jewish third-year from Brooklyn, New York is both a member of JGAF and on the steering committee of JOOOT. “It is vital for me to have a liberation, justice-based Jewish community on campus to vocalize these viewpoints and understand Judaism within the context of these movements,” they said. “I think that the institutionalization of Jewish spaces ultimately sanitizes Judaism to a point that it removes a lot of the heart and community feeling that I value so much about Jewish spaces. The warmth experienced in JGAF based on building and expanding community with one another, as well as the significance of being in homes, naturally emphasizes what is so valuable about communities like it.”

There are a lot of similarities between the students who took on the Jewish establishment’s general assembly back in 1969, the young Jews who, throughout the decades, took a leap to grow independent and self-sufficient communities on their college campuses, the Jews I have grown a community with on my very own college campus in Worcester, MA, and our Jewish ancestors who all brought us here today: We have all decided that the present isn’t inevitable and if there are conditions we want to change, we have the power to do so. It is important that independent Jewish student organizations continue on this path of resilience, never erasing the legacy of the Jewish organizers who came before us.

“Even though Lights in Action disappeared, we were really clear that we would come back, in a different form, and student organizing is that,” said Rabbi Jill Jacobs. “And I think some of the success is that some of what we were doing is not radical anymore, it is totally normal.”

Jewish organizers today might want to borrow a page out of the story of the radical Jewish students who have been building this movement for decades, from the protests in the 60’s, to the years of community building in the 90’s, and all that followed, to continue paving the way for the Jewish students of the future. As Jews we are taught to ask questions. Let us honor that tradition by questioning the systems that confine our Judaism, that tell us we have to accept the way things are. As Jewish students, as Jewish people, as Jews, it is not just our right, but more importantly, our responsibility, to fight for justice. Through our writing, our organizing, and our community-building, we shall pursue it.

צדק צדק תרדוף

Tzedek tzedek tirdof

Justice, justice, you shall pursue

If you would like to support NAJSA’s legacy of independent Jewish student organizing, consider making a contribution to the Jewish Student Press Service, which continues on its original 1971 mission to support Jewish students in finding their voices and speaking truth to power through journalism and action through New Voices Magazine. You can help protect the future of independent Jewish student publishing and support the next generation of Jewish progressive writers. To make a donation, click here.