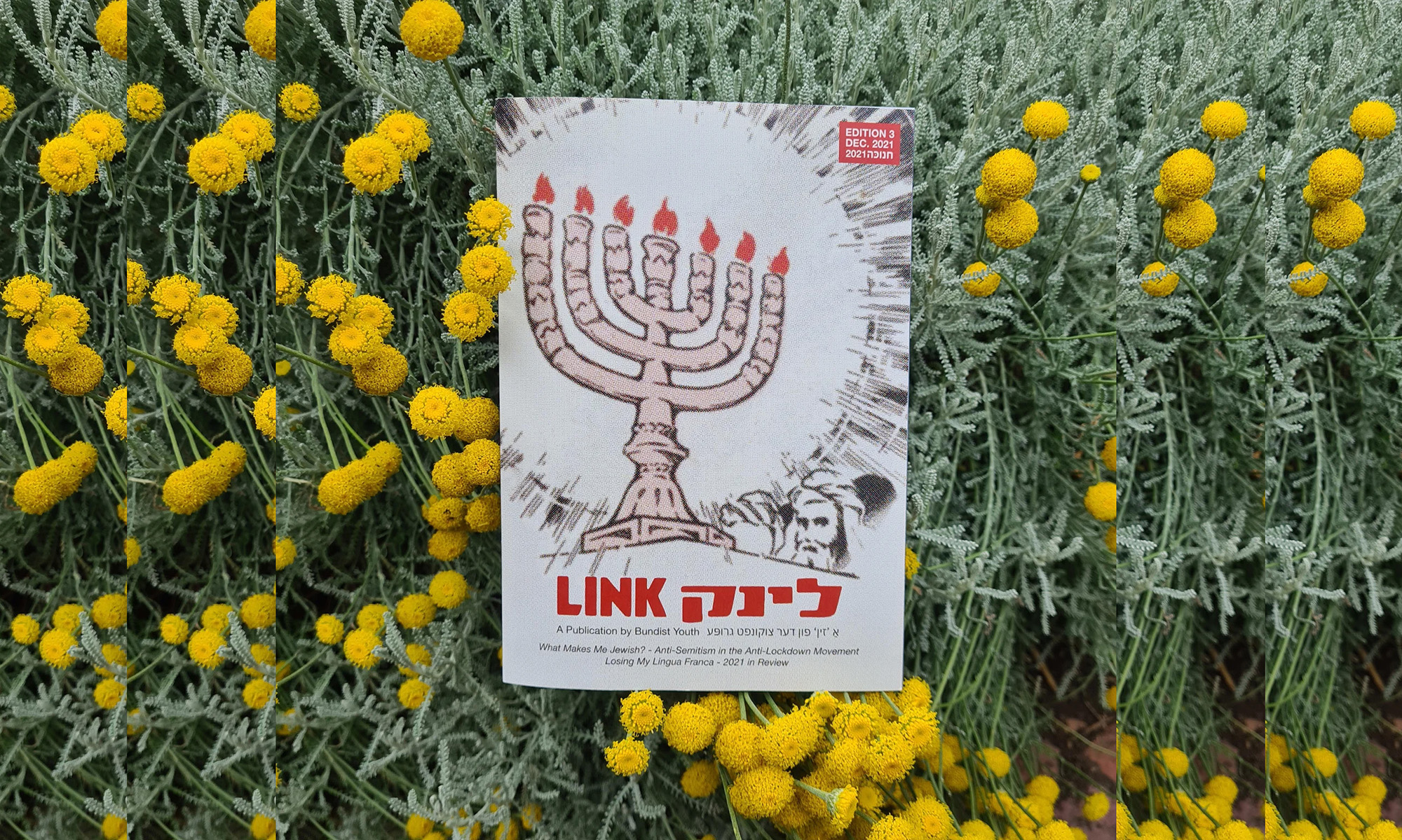

Welcome to the Jewish Underground Press! Our Jewish zine review columnist Miranda Sullivan gives us her takes on the hottest Jewish zines. You can read our columnist’s introduction to our zine review series here, or view other zine reviews here.

I was eager to see what the Jewish Labor Bund Zine “Link” would have in store. The zine does an effective job at explaining the current political moment in Australia, especially to a Jew living in the U.S., such as myself. Of course, with my Hebrew being lackluster and my yiddish nonexistent, I wasn’t able to fully comprehend two out of the twenty pages of Melbourne’s Youth Bundist Party’s Third edition of their zine. So to the author of “Teddy ‘Jewboy’ and ‘The Jewboy Gang’” I apologize for leaving you out of things. But the remaining writings made me wonder what is next for the Jewish community in Australia facing the rise of right-wing conservatism.

Founded in 1897, the Jewish Labor Bund sought to secure worker’s rights and human rights for the Jews of the Tsarist Pale of Settlement in Eastern Europe. According to their modern-day website, “The Bund’s messages of social and economic democracy, cultural autonomy and secular Yiddish culture were countered by the religious sector of the Jewish community, the Zionist movement and the capitalist wing of the Jewish community, as well as by right wing and semi-fascist elements of Eastern European non-Jewish society.”

For someone wondering about what the Bund stood for historically, the zine is informative. It includes a “Diggin’ The Archives” segment, where modern day Bundists take a look at older bulletins from the party and the zine contributors provide a brief commentary. In this edition, the zine contributors comment on a 1952 Bulletin that states the principles of the Bund are “against Zionism, for continuation of Jewish life where-ever Jews live; against assimilationism and Hebraization; for democratically elected Jewish community organizations; for the defense of democracy against Communism and Fascism.”

I find this final historical intervention fascinating, as the Bund is socialist. It makes me wonder, does the Bund equate communism and fascism to this day? I think the answer holds a bit of nuance, naturally, but my hope is that this false equivalency is rejected by the modern standards of the Bund. It brings up philosophical questions, such as, can a socialist organization be anti-communist? Is the Bund inherently anarchist by rejecting Zionism? Why does the Bund center defending democracy? I’ll leave those questions for the reader to ponder, but Atticus Invasto’s “Beneath Freedom’s Skin” section in the zine sheds light on how the modern Bund in Australia is handling the threat of antisemitism.

Invasto made me think about the state of Jewish progressivism, a topic well-covered in the Link Bund Zine, especially as it relates to anti-COVID lockdown protesters comparing their struggles to that of the Holocaust. Invasto discusses how, in both the U.S and Australia, there is a rise of antisemitic conspiracy theories and the militarization of right-wing nationalist groups. I thought the overview Invasto gave was thorough, but I did want to see more about what to do next when it comes to fighting the politics of right-wing antisemitism. We’ve got to bolster our arguments, people! We must say, and do, more than just repeat that Nazis are bad and we wish people would put on masks. Fighting off Nazis old and new has never been an easy task, but for some people in the here-and-now, this might look like engaging in Jewish ritual, rejecting Zionist and evangelical propaganda, advocating for a free Palestine, or building a community based around anti-capitalist values, Jewish or not.

This zine is formatted well — it’s readable (with the exception of yiddish and Hebrew for some readers) and it’s aesthetically pleasing. The zine has variety; poetry, essays, and cartoons. But having a zine, a Jewish zine no less, is largely about what is being said. For a zine from authors self-identifying as among the more left Jewish bastions, parts of it felt milquetoast.

The essay on Jewish identity “Vos Makht a Yid?” by Elysha Segal was touching, but a little confusing for someone with no primer on what SKIF is, the youth party of the Bund. “Shh, They Might Hear You” by Jordan King-Lacroix was unexciting, and for me, a bit frustrating. The poem is about not wanting to tell people that you’re Jewish in fear of confirming Jewish stereotypes. It begins by expressing hurt over people assuming the narrator to be cheap, sneaky. The ending deals with what King-Lacroix identifies as a “War-Monger” Jewish stereotype, as the poem touches on the topic of Israel. I can’t quite tell what King-Lacroix’s opinions are on the subject, and I’m unsure of the rationale behind their anger with the “War-Monger” Jewish stereotype. It’s my understanding that it’s a stereotype less rooted in hundreds of years of antisemitism like being cheap or sneaky, and more a response from Jewish people seeing Zionism as antithetical to Jewishness and as the embodiment of human rights violations against Palestinians, so it feels like a false equivalency to conflate the “War Monger” stereotype to the other ones. The poem is interesting when combined with Invasto’s exploration of the myths of left-wing terrorism (“the violence from anti-lockdown movements is the far-right threat that many politicians were comfortable ignoring or conflating with the myth of a growing left-wing terrorism.”) The begining of Jordan King-Lacroix’s poem might suggest right-wing antisemitism is ultimately more dangerous in Australia and the United States than so-called “left wing antisemitism,” but the ending made me wonder if King-Lacroix needed to read more from Invasto.

Perhaps Invasto’s piece, among many think-pieces from Jewish writers on modern day antisemitism, needed to have more focus on how to take our understanding of what it means to be Jewish when faced with an ever-pressing threat of the growing power of right-wing antisemitism. Perhaps this means that left-wing Jewry must more publicly support certain causes, or maybe it means organizing within the Jewish community to ensure people know the true history behind antisemitism. As so many people these days seem to point out, we are living in “unprecedented” and “uncertain” times. The Bund party is firmly grounded by its own history, and for that, they deserve deep appreciation as a Jewish institution. The Bund sets a good example for other Jewish communities because antisemitism is actually quite precedented and certain. If we can agree that history repeats itself, maybe this time around things can be different.

Photo credit to the Jewish Labor Bund for the featured image. You view their zine shop here to purchase your own copies of “Link”.