Welcome to the Jewish Underground Press! Our Jewish zine review columnist Miranda Sullivan gives us her takes on the hottest Jewish zines. You can read our columnist’s introduction to our zine review series here, or view other zine reviews here.

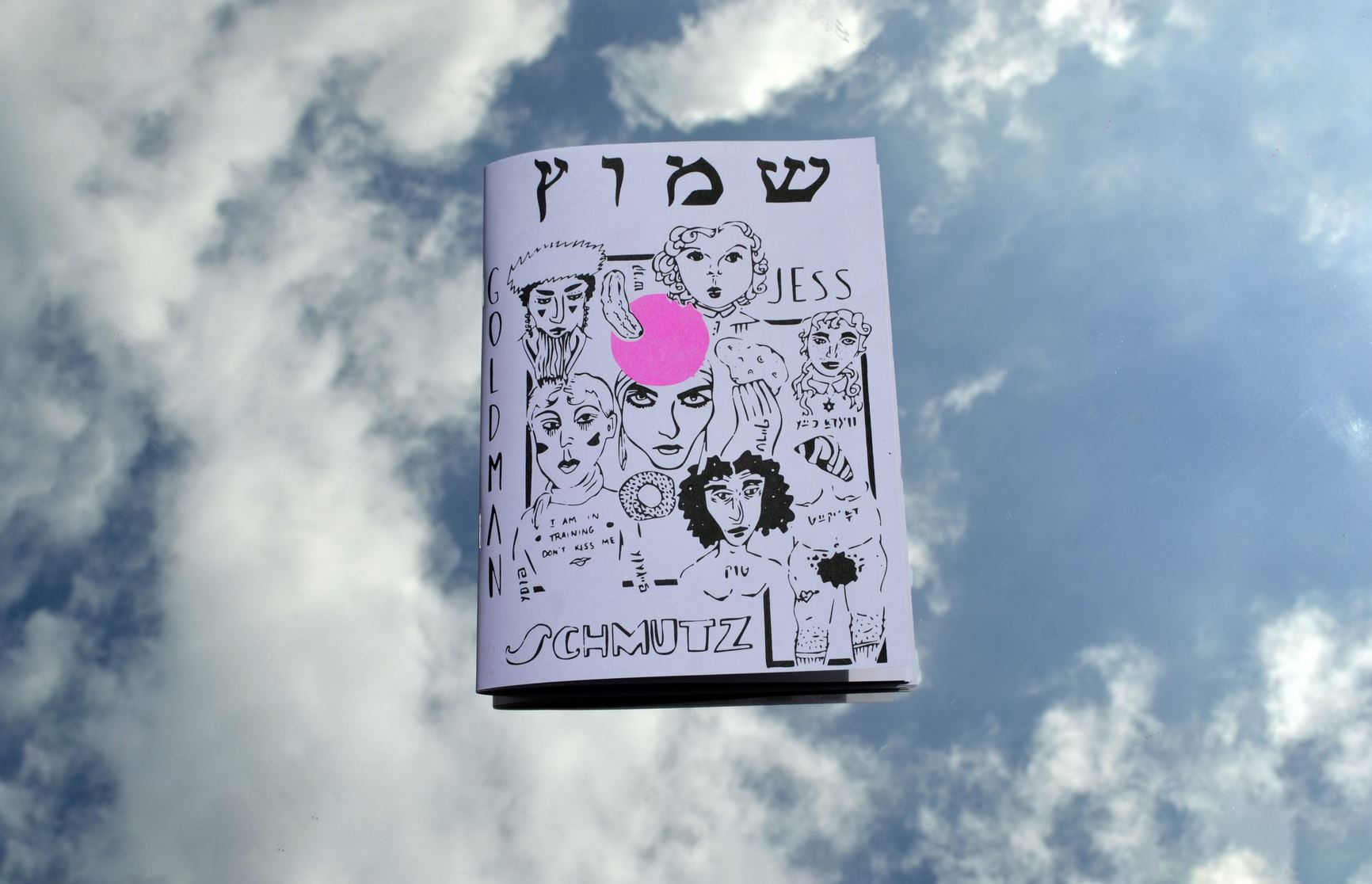

My favorite kind of art entails two things: it makes me think in a way I haven’t before and it inspires me to do…well, something. Whether that’s pondering what it means to be in the clouds or going down a lengthy Wikipedia search about Claude Cahun, Jess Goldman’s “Shmutz” stirred me to action. In their chapbook of three original midrashim, Goldman’s poignant, funny, and heartful voice shone through tales of goylem, verevolfs, angels, and demons.

Midrash, in my understanding, is an extrapolation or folktale retelling of an existing Jewish text, figure, place, or really anything — like the way a word is drawn in a Torah scroll or an oddly placed verse. That’s the definition I’m using for the purpose of this review, albeit a more Reform take than the traditional aggadot in the Talmud. Goldman doesn’t really use the word midrash, but the way they take stories and understandings of Jewish figures, such as Lilith or the goylem, fits my own definition of the term. Like the goylem, Goldman molds familiar characters and breathes a new life into them to highlight uniquely Jewish and queer experiences.

The stories, which are interwoven with the same characters, open with “Evelilith,” or its Yiddish title, “Tsvey Frayen Makht Beyz.” We don’t meet Lilith or Eve again in the following midrashim, but the story establishes an alternative biblical origin story: one where Lilith, imagined as the serpent, is not wretched for seducing Eve. Lilith draws Eve into a life of supernatural love, and opens Eve to a world of wisdom Adam told her she couldn’t have. Goldman sets out to reimagine yiddish folklore that historically has been used to reinforce heteronormative gender and sexuality expectations. Goldman is successful at blurring the lines between “the villain” and “the misunderstood,” using Lilith as an example of embracing not only queerness, but access to a greater understanding of Jewish teaching.

The midrashim I’ve read are often set in a pre-biblical time period of vague shtetls and villages. In “Shmutz”, Goldman gives us a modern interpretation of Yiddish folklore where the goylem kills skinheads in “The Goylem Nation,” or “Gaylem Land,” the chapbook’s second midrash, retelling Isaac Leib Peretz’s classic Der Goylem. In this version, the peckish Reb Avreymeleh Ben Yankl of Begyl Bergleh (in yiddish, “Bagel Hill”) creates the Goylem to defeat neo-nazis and their fascist leader, Fred. Reb Yankl is an “air man,” a term used to describe someone with their head in the clouds; but also a term used by Zionists negatively to describe stateless people. The Goylem possesses the stateless Jewish people of Begyl Bergleh, the Yidn, in what begins as a holy crusade against their oppressors but quickly devolves into the murder of goyim, or “non-Jews”.

By the time Reb Yankl realizes his Goylem has gone too far, it is too late for him to stop his creation. Instead of seeking justice for the innocent, Reb Yankl convinces the Yidn that the goyim are the enemies to make them feel better about killing them. Soon, only Yidn are left in Beygl Bergleh, and the “birth of the Goylem Nation” is declared, with the history of its origins grossly altered and goyim displaced or murdered. This midrash warns and retells the ways in which we can become like our own oppressors. It’s an important story, and one I hope continues to get retold and reimagined.

The final story in the zine is entitled “Blumeh’s Pleasure Quest,” or “Blumeh’s Hanae Zukhn” in yiddish. Blumeh is a secondary character of Begyl Bergleh, and her story takes place before the emergence of the Goylem Nation. Blumeh, scared of being vulnerable in intimacy, is guided by the ghost of Claude Cahun, who is a Jewish French Lesbian and gender non-conforming Surrealist artist. Cahun takes Blumeh through the life of her queer ancestors which teaches her to embrace her sexuality and get in touch with her innermost self. It’s a story of self-discovery and of honoring thy ancestors. The story concludes the three midrashim on a note of hopefulness, with Blumeh happily reunited with her lover, and more importantly, united with a part of herself. That is another theme I enjoyed throughout the chapbook; that no matter when or where you live there is always an opportunity to ground yourself in your own cultural history and use that as a platform for your own self discovery.

Goldman’s chapbook has an earnestness that feels authentically Jewish for its humor, appreciation of the Jewish family, and a sharp eye towards progressivism. Moments of seriousness are bookended with light hearted humor or a clever word choice (I particularly liked the naming of Begyl Bergleh, translated as “Bagel Hill”) while the stories themselves can be interpreted through numerous lenses. This only broadens the scope of the chapbook and it deepens its meaning. Judaism contains multitudes, as do the stories told.

Midrashim are used to teach us. The best midrashim hold more than one interpretation. Perhaps that’s why it’s such a long lasting form of Jewish writing; the memorable stories encourage readers to want to keep the stories going, to grow them, to give a full history to every character. Goldman not only wrote engaging and smart stories, but she gave space to tales of Jewish queerness, Jewish love, and the harms of hate in the name of Jewishness. I hope others get excited by Shmutz, and that it inspires more midrashim to come.

Photo credit to the pink peacock for the featured image. You can purchase a copy of “Shmutz” here.