The Editor of UChicago’s undergraduate journal for Jewish Studies joins New Voices Magazine to discuss the publication’s newly re-imagined digital release. You can view the virtual edition of mkwm here.

For the past decade, on and off, the University of Chicago’s Greenberg Center has produced an undergraduate journal for Jewish Studies called Makom. The title of this journal was a transliteration of the contemporary Israeli pronunciation of the Hebrew word מקום, meaning “place”. After a two year hiatus during which the journal was not released, I was approached to be its editor for the 2021-2022 academic year. I accepted, knowing there were changes I wanted to make.

First, I wanted to move the journal from a primarily physical to a primarily digital format. This was inspired mostly by the material conditions of this quarantine year. In previous years, the physical copies of the journal could be circulated through the flow of students on campus. It was simple to deposit a number of journals in common spaces where they would be picked up, read, and kept or left somewhere else for the cycle to continue there. COVID made this model impossible and, adapting to a pandemic world, I preferred a digital release. This was also supported by my work on In geveb, an incredible online journal of Yiddish studies. Even in non-COVID years (let’s pray for some), an online journal is much more accessible to a much wider audience than print. An online journal can be accessed across wide distances by as many people who want to read it without regard for the pierce of post and printing and unbound by the physical conditions of institutional affiliation. This is one of those radical kernels of this COVID year that should be remembered and brought beyond it.

Second, I wanted to modify the name. As a student of Yiddish, when I read מקום, I pronounce it mokem. This difference between Israeli makom and Ashkenazi mokem is not purely phonological. In Yiddish, the standard word for “place” is the Germanic ort. In idiomatic Yiddish mokem, set apart by its loshn-koydesh (Hebrew and Aramaic) etymology, is usually used ironically. A shtetl, a ghetto can be referred to as a mokem, that is, a place as places are in the tanakh, performing the conditions of exile: the comic rupture between the Jewish symbolic world and diasporic Jewish material reality. I wanted this reading, my Yiddish reading, to be present in the journal. But I’m also greedy: I wanted it all. I wanted mokem, I wanted makom, I wanted a kuf pronounced deep in the throat as in Arabic, I wanted stares of incomprehension and invented pronunciation. As such, I decided to default to those four characters מקום wherever possible. As a Latin representation, I settled on a German transcription: mkwm.

With all the aforementioned in mind, I settled on a theme for the journal: digital diaspora. Diaspora as in, of course, diaspora – in all its manifestations. Digital twice over: first, in the more conventional sense of the term, i.e., internet, computers, etc., but also in its more etymological sense: as in digits. That is to say: as in figures that are always separate from each other, whose combination (which always evokes the space between them) produces meaning.

As a Jew I put my faith in the productivity of rupture and in the transcendence thereof: in dveykes (cleaving). I am tormented by irreparability, the constancy of separation, but I am fascinated and inspired by the creation that takes place within this separation, whether it be intersubjective, temporal, spatial, linguistic, or (as it always is) some mix of these. As an editor, I sought to create a space to showcase this productivity and, god-willing, to inspire more.

Each of my contributors dealt with different ruptures in different ways, often in- and outside the traditionally recognized bounds of Jewishness. Their contributions come from a variety of genres (two essays, two series of paintings, a series of translated poems, a comic, and a digital humanities study) — another divergence from the essay-driven format of the Makom of previous years. They come from very different angles, and I find, of course, that they work best when the space between them is considered. In order to give you, dear reader, an outline of the journal with all of its negative space intact, I will now provide a sort of annotated table of contents.

From Giancarlo Venturini I received a series of paintings entitled Through Borders, Through Time. The paintings, which depict the small Polish town of Radzyń Podlaski, are diaries of a place where the painter was not, and the desire produced in that separation bleeds from each one.

Holly Robins submitted an essay entitled “The Return of the Holocaust’s Dead: Oblivion and Awakening in Polish Prose and Cinema.” This piece considers spectral remainders of Jews in contemporary Polish art, especially represented as ghosts, returning to haunt Poles of the present day. All these works, Robins argues, are attempts to stage and handle the rupture of Jewish absence in Poland, which is constantly present especially in its repression from common memory.

From Dikla Taylor-Sheinman I received an excerpt from her BA thesis entitled “American Jewish Feminists of the 1970s and 1980s and the Question of Palestine.” This section dealt with the reaction of American Zionist feminists to the question of Palestine in the women’s movement. Taylor-Sheinman reveals their conduct to be highly disappointing: they silenced third world and Soviet representatives who spoke on Palestine, accusing them of “politicizing” feminism and of being mere puppets for their sinister men. It is clear that Taylor-Sheinman is disappointed by this incoherence, and her cutting, methodical examination of this failure is a brilliant, cathartic piece of scholarship.

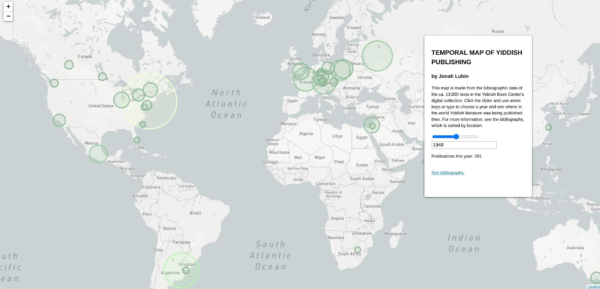

My own contribution to the journal is a digital map of Yiddish publishing which maps around 13,000 of the 15,000 entries in the Yiddish Book Center’s Spielberg Digital Library. By scrolling forward and backward in time, the fluctuations of Yiddishland, in all its migrant flexibility, are made visible.

Viktor Matyevsky sent in a series of poems by the Soviet writer Dovid Hofshteyn translated from Yiddish. These poems, which were written in the first half of the 20th century with all its promise and calamity, were selected from an artificial collection of his work entitled Ikh gloyb (“I believe”), which was put together and published by the Yidisher Kultur Farband (Yiddish Cultural Union) in New York. Hofhsteyn, along with the rest of the Soviet-Yiddish avant-garde, was killed by Stalin in 1953 on the so-called Night of Murdered Poets.

From Rena Yehuda Newman (the editor of this very publication) I received a comic entitled Tehillim for T. Through its visualization of the intimacy of digital conversation, this piece confronts and depicts the productivity of rupture in terms of time, space, and tradition: the collaboration between friends physically separated to find queer precedence in the book of psalms.

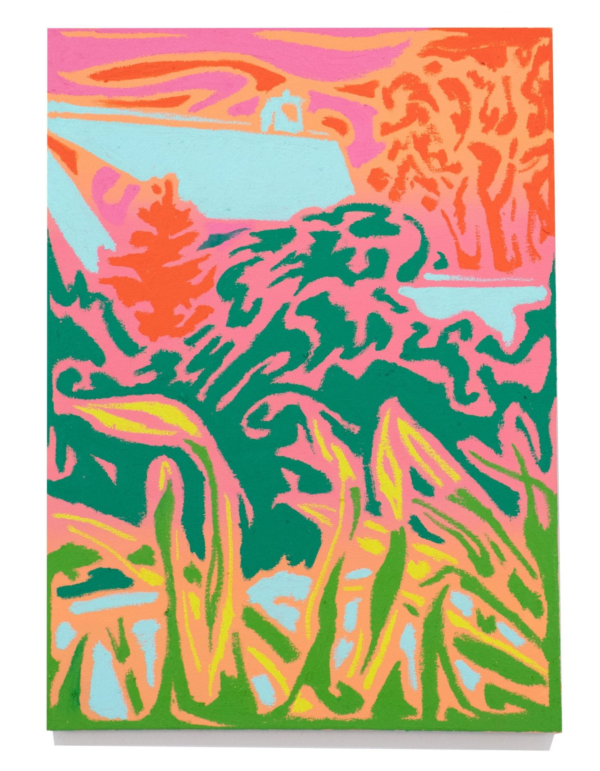

David Yang brought a series of paintings entitled The Hong Kong Series. Inspired by Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series, which depicted the movement of black laborers during the great migration, Yang depicts the Hong Kong protests of 2019, and in treating these particular manifestations of collective resistance imagines new and radical forms of transnational solidarity.

I am so excited that I get to share these pieces with you. My contributors are brilliant young scholars and artists who come from different places and have divergent aesthetic and intellectual backgrounds and preoccupations. A whole world is contained in their work, and many words are to be expected in its continuation. These are brilliant but brief moments in the ruptured dreaming of the rising generation of diasporic thinkers, and I am honored to have been able to snapshot a moment in their stunning juvenalia.

The entire journal can be read here: https://mkwm.humanities.uchicago.edu/. It looks best on a computer. For more information, questions, responses, submissions to next year’s edition, or if you are interested in purchasing a copy of our limited print run, please contact mkwm@lists.uchicago.edu .