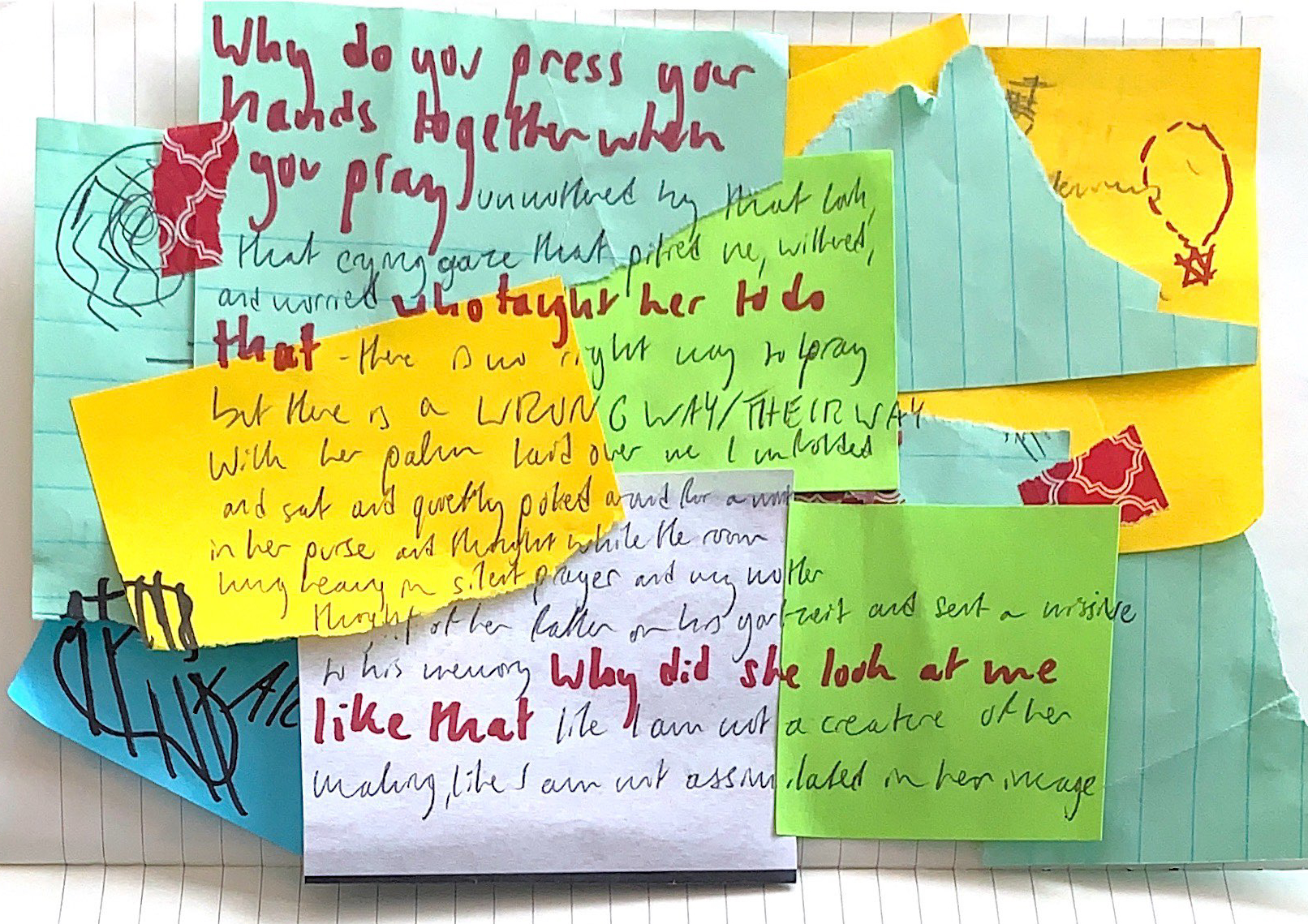

The feeling is almost routine to me now. I sit at my cluttered desk, overwhelmed by the assignments looming over me, causing me to dread even opening my laptop. So I don’t. I open my desk drawer and reach into my tote bag, rifling around my room and pulling out handfuls of paper scraps – old to-do lists, flash cards, cheat sheets, and more in all colors and sizes; yellows and lime greens, lined and unlined sheets marked up with red and black ink, in cursive and print, block letters and sloping calligraphy. I collect these bits of detritus and arrange them like a jigsaw puzzle within the pages of my spiral notebook, using jagged pieces of tape and the sticky ends of Post-It notes to hold everything together. This combined act of rummaging, collaging, and writing demands my undivided concentration. Once I find a comfortable place to stop, I notice that hours have passed me by. My workload remains, trapped inside the computer I refused to open, but my head is clearer, my body less tense, my breath more even.

Since long before the pandemic, but especially in recent months, I’ve started holding on to the meaningless bits of paper that pass through my hands from day to day. Instead of throwing away these bits of stationery after they become useful, I keep them as a physical reminder of my days otherwise spent in a virtual world. I fill my notebooks with them, making a wallpaper on which I mount words with deeper intention, words that I deem more valuable than reminders to wash my dishes or turn in my essay before midnight. I cannot handle these objects the same way anymore; I can’t discard them, or find a truly meaningful place to put them. What is the point of paper in this digital world? Why write anything down when it can be recorded on my phone, and beyond that, why keep the scraps? In the new Jewish friendships I’ve formed over the past year, I’ve found that so many of us turn to journaling in some capacity to answer these questions; journaling is a way to organize the chaotic, fill up the emptiness, and find beauty in our everyday lives.

There’s a concept in Judaism called tzimtzum. It expresses the notion of a divine contraction, a turning inward that God did when They created the universe. For all of time there was nothing, and then, after retreating to an internal space, there was the energy to create everything. Judaism, to me, is something that fills up the emptiness, something that makes sense of what is senseless, a lens through which confusion turns into peace. In times of transition and stress I become reinvigorated as a Jew, taking renewed pride in the rituals I was raised on and finding joy in the rituals I get to create myself. The in-person, institutional Jewish communities in which I’ve always positioned myself – summer camp, synagogue, etc. – have become unavailable to me as I’ve aged and as the world has attempted to navigate COVID-19. Now for the first time in my life I am taking my Jewish journey alone. The notion of contracting inward is something that initially frightens me, even now, more than a year into quarantine and social distancing. I’ve learned, however, through practices like journaling that demand mindful solitude, that our internal worlds are as full of life as our communities, and the potential we have to worship, create, and live on our own is limitless.

I first began journaling at Jewish summer camp as a child. I remember feeling so surrounded and elevated by the love of my peers and mentors to the point that poetry began pouring out of me, and that’s how my writing career began. There’s a reason that a Jewish space played a direct role in my creative life; the notion of divinity existing within both group spaces and the individual self is a distinctly Jewish thought that comes to mind every time I sit with the intention of creation. The paying of careful attention, the small details and references that matter only to the creator, the acknowledgement and acceptance of the flaws, conflicts, and passions that fill up the artist’s head and page; this is the making of personal artwork, journals, diaries, and more. Journaling, collage, and creative writing have combined in our notebooks to provide the ultimate outlet, one where our Jewish identity is free to expand and condense.

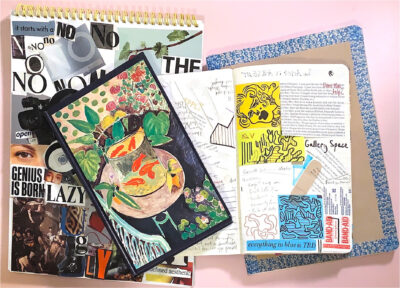

Judaism, like journaling, is a combination of the spiritual, the creative, the practical, and the personal. Lena Ben-Gideon, a first-year

student at Brandeis University, uses her notebooks to contain the multitudes of her responsibilities, her thoughts, and her goals. Academic organization and an artistic outlet combine in her bullet journal, but her illustrated siddur is a unique project that combines her love for journaling and ongoing Jewish thought.

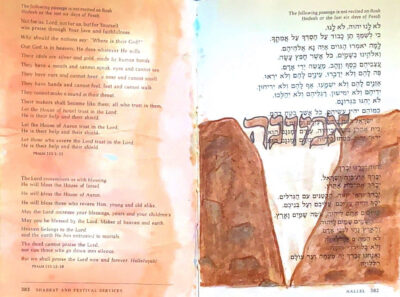

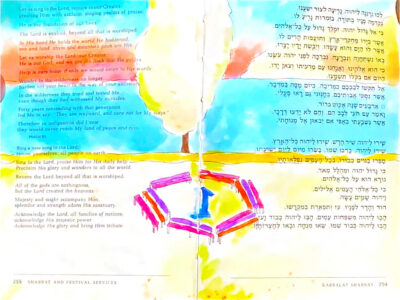

Ben–Gideon began her illustrated siddur project last year in the middle of the pandemic. The idea began when Ben-Gideon drew inside of a siddur as a gift for a friend. “I loved doing it so much, and it was therapeutic for me,” she said, and decided to create one for herself. Based on her interpretations of the prayers and blessings she’s known for her whole life, Ben–Gideon conceptualizes and creates drawings in the physical siddur that reflect the messages she takes away from the text. One of her spreads contains the words to the Barchu, which Ben-Gideon visualized as the “the connection between day and night.” She drew two hands connecting, one representing light and the other darkness. Other spreads show geometric patterns along with traditional Jewish images, like the eternal light and the parted Red Sea.

The goal of this project is not to create finite associations between prayers and images; Ben-Gideon also writes questions that inspire mediation and thought on the sides of the pages, hoping to spark a continued relationship with this text that changes form upon every rereading. Like journaling, illustrating this siddur provides an opportunity to create artwork that can grow and change along with the creator. The process of filling a whole siddur with images is daunting on purpose. “It’s a constant work in progress,” Ben–Gideon said. “It’s not finished. I don’t think it’ll ever be finished. But that’s something that’s constantly inspired me.”

Many of the other Jewish journalers I know, whether their work relates to their identity or not, find solace and a meditative power in practicing this artform. Their projects are a representation of the whole world through their eyes, a tangible object that makes distant memories and looming anxieties accessible through art and writing. For many journalers, the idea of scheduling regular time to journal feels limiting.

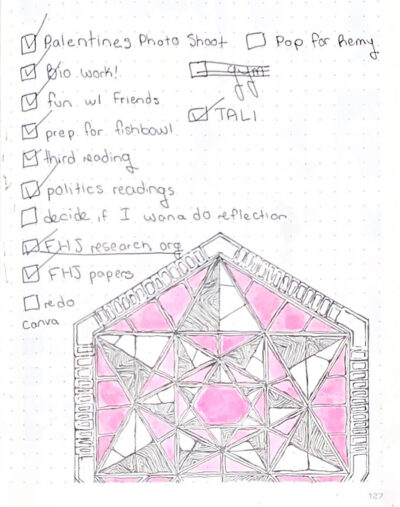

“I’ve always liked the idea of a journal,” said Tali Meisel, another first-year student at Brandeis University. She remembers receiving a journal for her Bat Mitzvah and beginning to write in it while reading Anne Frank’s diary. “I was at a new school and it was a hard adjustment for me. I spent significant time over the next few weeks after [my Bat Mitzvah] trying to write down every single detail in my journal.” The attempt to recall every detail of the event was eventually futile, and Meisel found that experience to be indicative of her relationship with journaling in general. “When I would try to write in my journal often or a certain number of times, that kind of pressure made me not want to do it.”

Recent exploration of her Jewish identity has brought writing practice back into Meisel’s life, especially around the High Holidays. “The last few years, I’ve been journaling on Yom Kippur,” she said. Meisel began this practice the fall of her senior year of high school. “It was a very uncomfortable experience at the moment, and I think it was really cool to have had the opportunity to do that because I basically just wrote down my thoughts. I didn’t force myself to keep going. I [produced] a lot of stream-of-consciousness writing, and I tried to make a list of things I was grateful for. That was a time where I wasn’t journaling to remember things later, it was to get me through the moment and to figure out what I would discover about myself. I haven’t done anything quite like that since then. This year on Yom Kippur, I did journal. I felt like I was in this removed state from normal life, and that was really special.”

Journaling for Meisel is a unique and inspired practice, one that has the capacity to contain the internal self rather than simply record one’s thoughts. “I have not gone back and looked at what I wrote since [Yom Kippur], but I felt a big sense of relief after doing that, like I did something that I needed to do for myself.”

Not every Jew is drawn to journaling, writing, or visual art. Everyone, however, has their own unique practices that allow them to embrace their creativity and introspect. Relating to the notion of tzimtzum, we can empower our internal selves through activities like journaling that encourage us to explore our own thoughts and experiences, creating something of beauty for ourselves. The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged my Jewish identity and caused me to create new methods of private worship and practice. Although I’ve always found strength and comfort in journaling, I now bring a consciously Jewish perspective to this art, using Jewish themes and questions to inform and challenge my work. Through this solitary act of creation, whether the artist writes, draws, or uses a completely different medium, we find ourselves grounded in a Jewish practice that helps us explore and grow our internal selves.

Lila Goldstein was a 2021 Resilient Writing Fellow with New Voices Magazine and the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. Featured image from the author’s own Jewish journal.