Via @jewsagainstfash on Instagram

“Under the heading ‘Jews raid Nazi’s home,’ the Daily Telegraph reported that ‘more than 100 people – most of them young Jews – stormed through a Melbourne Nazi leader’s house today and ransacked it. They smashed every window and glass door, set fire to clothing and scattered literature and files everywhere. The kitchen stove was ripped out and left lying on its side. A bungalow at the rear of the house was also wrecked and a car parked in the drive had all its windows broken…

“The Melbourne Herald reported that the demonstrators, ‘most claiming to be Jews, hurled bricks, rocks, and metal through the windows. Some of the group carrying red flags, broke into the house and smashed everything inside. Bedding, furniture and a TV were hit first. Then an office with a padlocked door was broken into, files were thrown out and cabinets overturned. A stove was ripped out and a refrigerator tipped over in the kitchen…

“A television team from Channel nine covered the attack throughout. Several members of the crowd appeared hysterical, most were shouting or screaming. (the only cry intelligible to the writer was ‘Smash the Nazi cunts!’)”

From ‘everybody wants to be führer’ on the attack of Nazi home in St Albans in 1972

PEELING BACK THE MYTHOLOGY

The Jewish community’s overwhelming conservatism in so-called Australia is nothing new; Jewish presence on this continent dates back to colonisation in 1788. While mainstream Jewish institutions remain right-wing and Zionist, Jewish communist, anti-fascist, and anti-colonial movements – and memories of them – are bubbling into awareness for many young Jews such as myself.

History, though, is easily manipulated, misunderstood, taken out of context. Searching for historical precedent for contemporary Jewish leftist ideas and movements, our communities have built up mythologies around very real historical events, obscuring more complicated, imperfect realities. A compelling piece of this history is the 1972 attack on a neo-Nazi HQ by over 100 young people on the unceded land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation, in so-called St. Albans, Melbourne.

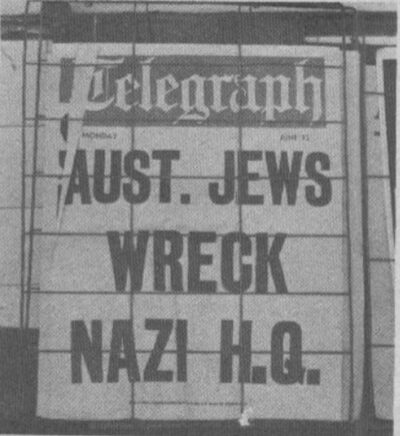

I first encountered records of this political action through an instagram post made by Jews Against Fascism, a collective which shares anti-fascist news and media from a Jewish perspective. A photograph of the front page of the Telegraph reads “AUST. JEWS WRECK NAZI H.Q.”

Dr. David Zyngier, a local representative for the Australian Greens Party, left a comment. “I was one of those young Jews there that day. Together with the Monash Labour Club, Workers Student Alliance and Wharfies and Builders Labourers Unions.” Projecting my own desire for a radical Jewish leftist community onto the past, I thought this must be a huge, hidden piece of Australian Jewish history I was about to uncover.

Speaking on the phone with Dr. Zyngier, he was quick to burst my bubble. He explained to me that the event was not mainly attended by Jews, as it was reported — in fact, as a member of the Radical Zionist Alliance, he helped organise the event across party lines in the far radical left, including socialist Zionists, and non-Jewish Maoists, Trotskyists, labour unions and worker-student alliances.

“This was less about antisemitism and more about anti-fascism. That’s my strong gut feeling about it. The view was, Nazis are fascists and fascists need to be defeated. While from a Jewish perspective of course we were concerned about the antisemitism, and I’m not trying to say that this wasn’t an issue for the non-Jewish left, but this was seen as part of the broader struggle against imperialism and fascism.”

Similar to actions taken against the Vietnam War and South African apartheid, the left saw this action against a neo-Nazi presence in Australia as broadly interconnected in a global network of resistance. It was particularly interesting to learn that at the time, Maoist and Trotskyist groups were willing to collaborate with socialist Zionists — the sort of alliance you wouldn’t find in any radical leftist movement today, as international outcry against Israeli apartheid reaches a fever pitch. Rather than further the myth that this attack on the Nazi HQ was a piece of singularly Jewish history, I began to see this event in all its contextual complexity. I needed to unravel this mythology of the Australian Jewish left which was building up not only in my mind, but in our collective memory also.

“What was most significant about the event was that we surrounded the HQ at St. Albans and put the Nazis inside to fright,” Dr. Zyngier said. “They fled, and we got hold of their files, which meant we had their membership lists, and that caused them to disappear. I recall seeing filing cabinets thrown out of a window, a most amazing event. We all felt at St. Albans like we had achieved an amazing victory. We were kidding ourselves of course, but we thought we had struck a blow against fascism that day.”

Some Jewish community leaders didn’t feel the same, with Laurence Einfeld from the New South Wales Jewish Board of Deputies condemning the attack, arguing that it had “[given] the Nazis thousands of dollars worth of free publicity.” Mr. Einfeld believed that “[there were] better ways to handle a menace such as the Nazi Party.”

“That enraged us even more,” Dr. Zyngier recalled. “And at the same time, we [the Radical Zionist Alliance] were demonstrating outside Israeli independence day celebrations at the Palais in St. Kilda, and getting attacked by the Jewish community. We were handing out leaflets calling for a 2 state solution and withdrawal from the West Bank, and we got attacked by Jews, punched and spat on.”

It’s not entirely surprising that socialist Zionists such as Dr. Zyngier have been met with such violence from Jewish communities here for being critical of the Israeli state. Though there are plenty of Jewish Israeli citizens who disapprove of their government, to speak even somewhat critically of the Israeli government in a Jewish-Australian context is often grounds for harassment and ostracisation — and it’s been like this for a while. How did our communities come to be this way?

ORIGIN STORIES

Dr. Max Kaiser, a researcher of Australian Jewish anti-fascism in the 1940’s and 50’s at the University of Melbourne, explained to me that Zionism wasn’t always a cornerstone of Jewish Australian institutions. Along with the Bund, which didn’t support Zionism, some Jews in Melbourne and Perth were particularly skeptical of Zionism from 1939 – 1948, due to their loyalty to the British empire.

In conversation with many of my other sources, we speculated a connection between Australia’s high intake of Holocaust refugees and the Jewish community’s conservative Zionism. There’s a collective assumption in Jewish communities that Holocaust survivors who came to Australia brought a staunch Zionism with them, a survival strategy in response to the trauma of the Holocaust. However, Dr. Kaiser’s research has led him to a different conclusion.

“There’s this way that Jewish Australian history is told, where the fact that there are so many Holocaust survivors here has some automatic relationship to being more conservative and more Zionist. A big finding in my research was that, no, Holocaust refugees and their allies were connecting Holocaust memory to a wider political, anti-fascist struggle.” In his research, Dr. Kaiser particularly investigates the Jewish Council to Combat Fascism and Antisemitism, a Melbourne organization present in the 40’s and 50’s that monitored and responded to antisemitism and fascism more broadly in the Australian context.

Rather than a result of an influx of Holocaust refugees, Dr. Kaiser believes that Zionism’s stronghold in the Australian Jewish community is, in significant part, a product of Cold War allegiances. “Another part of this was the Zionist Jewish right’s suspicion of having meetings about the plight of Aboriginal people, because it was seen as a left-wing, communist cause. [They chose] a safer political option, which is a continuing theme in Australian Jewish politics. I think how the Jewish community thinks about its relationship to Indigenous people now, it’s just become this complete mythology.”

Zac Roberts, an Aboriginal Australian from Yuin Country and researcher of Indigenous / Jewish relations from 1788 at Macquarie University, certainly echoes this sentiment. “Most of what’s been written about Indigenous / Jewish relations has been by Jewish people […] I do think there’s a significant relationship, but often this relationship is simplified and overstated from the Jewish perspective.”

A significant piece of this simplified, overstated history concerns activist and Yorta Yorta Elder William Cooper, who led a deputation of Indigenous people to protest the persecution of Jews in Germany, one month after Kristallnacht in December 1938. While there were protests all around Australia following the Kristallnacht pogrom, Cooper’s action is often discussed as being one of the “only protests of its kind at the time”. Much of what’s been published about him concerns this act of solidarity, and Cooper’s protest has become a touchstone for Jewish Australians looking to cultivate relations of solidarity with Aboriginal communities and their justice movements.

Aboriginal scholar Professor Gary Foley argues that this was in fact a strategic action to draw attention to the similarities between what was happening in Nazi Germany, and the treatment of Indigenous peoples in Australia. Roberts explains to me that when Jewish Australians discuss Cooper’s action at the German Consulate in 1938, they tend to gloss over his context as a Yorta Yorta Elder and activist.

“Cooper’s whole life was about Indigenous rights. He ran the Australian Aborigines League out of his dining room. As nice as it was that he was standing up for the Jewish people, looking at the trajectory of his life and work it was actually him going, ‘you’re all real mad about this, what about the black people?’” Roberts said.

Roberts also discussed whether this tendency to mythologize historical Jewish / Indigenous relations erases Jewish Australians’ complicity in colonialism. “You can’t erase the fact that first of all, Jewish people were on the First Fleet, they were part of the first settlers, and were accepted as part of the British people in that period. And that makes them a very specific kind of settler. Yes, Jewish people were some of the first non-Indigenous people to say this land was invaded. But you can’t then erase all of the racism that was done as well, which is also in the historical record. You can’t pick and choose.”

“In the early 1930’s, a Jewish man named Melech Ravitch did a massive road trip from Adelaide to the Northern Territory, through the Kimberleys and whatnot, for the purpose of figuring out if the Northern Territory of Australia could be the Jewish homeland. It’s part of what was called the Kimberley Plan.”

At a time when all kinds of colonial proposals were being made about where a Jewish nation-state could feasibly be built, it’s unsurprising that stolen, invaded Aboriginal lands in the Northern Territory were considered too. “This man [was] someone who’s been historically colonized, actively going out and searching for a place to colonize. And not really having any self awareness about the fact that that’s what he was doing.” said Roberts.

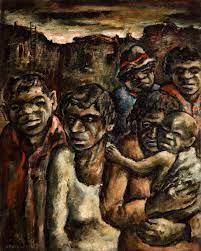

Ravitch’s son, an antifascist artist named Yosl Bergner, began painting urban Aboriginal peoples in Melbourne in the late 1930’s. “It was the first time that Indigenous people were depicted in non-Indigenous art as a colonised group of people who were experiencing genocide, rather than as a racist caricature.”

While Bergner’s paintings are often included in a narrative of a progressive, historical Jewish-Australian community, they continue this colonial relationship between Jewish and Aboriginal communities. I wonder who the unnamed Indigenous people Bergner painted were, and if they saw any royalties from his paintings? It calls to mind the orientalist, Ashkenazi anthropologists who travelled to SCWANA regions to document Jewish communities there.

ON SOLIDARITY

Roberts believes that broadly, Jewish Australian communities have not reckoned with their position as settlers on these unceded lands. “They don’t have this self-reflection, and I think that speaks to the conservatism of Jewish communities,” he said.

In his own family, three or four generations of Yuin men have married Jewish women, and Roberts’ mother is also a patrilineal Jew. “The way that [Indigenous / Jewish] relationships have changed over time is that they’ve become less personal, and more about social justice. In the 19th century we saw a lot of marriages, friendships, and also professional relationships between Jewish and Aboriginal people, but now these relationships tend to remain within the bounds of activism. There’s less of a human element to it, and I think that’s potentially partially because of how Jewish communities speak about these relationships. They’re so intent on helping that they start to deny Aboriginal people’s agency. It becomes paternalistic.”

“Bringing back that human element, that personal element, could make it a much more reciprocal relationship. If that’s going to happen, the fact that non-Indigenous Jewish people are settlers in this country needs to be acknowledged. There needs to come a time where Jewish people do the listening. I think that’s going to be the hardest bit, and potentially the most rewarding.”

Roberts and I also discussed whether Jewish Australian communities’ refusal or inability to recognise Israeli occupation might be a barrier to growing these relationships. “Indigneous people relate a lot to the Palestinians! Whereas Australian Jews are very much drawing the comparison between themselves and Indigenous Australians. Indigenous people aren’t necessarily aligning themselves in the ways that [Zionist] Jewish institutions want them to.”

Relationships of solidarity between Aboriginal Australians and Palestinians emerged in the late 1970’s, with both communities recognizing shared threads in their experiences with state citizenship, dispossession from land, and incarceration. At the 2019 Black-Palestinian Solidarity Conference, attendees recognized the shared racism of Australian and Israeli nation-states, investigating the possibilities which alternative forms of identity and community offer for non-racist futures.

In 2020, the Australia Palestine Advocacy Network (APAN) released a joint statement on antisemitism with the Australian Jewish Democratic Society (AJDS). In conversation with Nasser Mashni from APAN, Dr. Jordy Silverstein discussed the broader ideas which informed the launch of the Joint Statement on Antisemitism. “It’s knowledge of what nation-states, antisemitism and racism look like in its most awful forms that brings [us] into conversation […] Our friends are those who are anti-racist wherever racism exists, wherever antisemitism exists, wherever anti-Palestinian sentiment exists.”

Dr. Silverstein, a historian at the University of Melbourne whose research explores sexuality, gender, racialization and nation-building, tells me over zoom that she was initially introduced to Palestinian rights advocacy through engaging with Indigneous knowledge and movements in this country. Her first year university class on ‘Indigenous Politics and the State’ with Dr. Wayne Atkinson, who is Yorta Yorta, prompted her to think critically about her position as a colonizer on unceded Aboriginal land, and by extension her understandings of and relationship with Israel. “There were a few moments and conversations from that class that have stayed with me 20 years on […] it led me to doing so much reading and learning, and thinking and talking to people.”

ORGANIZING FUTURES

Dr. Silverstein is one of several Jewish Australians interviewed by Kea Cranko for her recently released documentary, “In Dialogue: Jews on the Borderlands.” The documentary explores ways in which Australian Jewish establishment structures mandate support for the state of Israel as an essential component of Jewish identity. Through engaging with non-Zionist Jews who have largely gone unnoticed by the mainstream, she hopes to spark dialogue within and beyond mainstream Jewish institutions, and work towards building Jewish spaces of plurality, diversity and tolerance.

Sitting down with Cranko at the Palestinian-owned Khamsa Cafe in Newtown, we jumped right into her relationship to Judaism. “I went to Emmanuel primary school, and felt dissociated from the Judaism and Jewish culture that was promoted there. I became quite removed from Judaism for a long time. One striking thing at Emmanuel was the three flags that fly in front of the school — the Australian flag, the Aboriginal flag, and then the Israeli flag. I now feel they’re quite at odds with each other.”

“It was discovering non-Zionist Jews in Palestine solidarity spaces that began my discovery of alternative iterations of Jewishness, which I’d never seen. But the vibrant socialist, communist, diasporic history of our communities is virtually imperceptible when I look at the current Jewish communal landscape, especially in so-called Sydney.”

Also interviewed in Cranko’s documentary is Vivienne Porszolt, from Jews Against Occupation NSW. She describes the organization to me as a secular, modernist humanist, and elderly group, with her being one of the youngest members at age 80. While the organisation attends rallies, puts out media releases and interviews, and partners with larger organisations, Porszolt is currently interested in organising across the generational gap which has emerged in the Australian Jewish left. We also discuss this gap in terms of modernists versus post-modernists, older heterosexual men versus younger queer people, and secularism versus spirituality.

Some of these generational differences, as well as differing relationships to Zionism, may also account for a recent split in the Australian Jewish Democratic Society. After the organization announced its collapse in mid-2020, it re-emerged in 2021 with what Porszolt calls the “old-guard” leadership, with many younger members having left the organization. As a young person searching for like-minded peers and community, it certainly feels as though there’s an organizational vacuum in the Australian Jewish left right now.

Jews Against Fascism, the social media collective through which I initially encountered the 1972 Nazi HQ attack, shared with me that they launched in 2016 following the islamophobic Reclaim Australia rallies, which were “becoming a serious honey pot for neo-Nazis.”

When asked how they see the Australian Jewish community, & media landscape, they wrote: “We are part of the Jewish community, but we definitely feel we are on its margins. It feels incredibly conservative, often reactionary, and profoundly Zionist, middle class, white and Ashkenazi. And the media landscape reflects this.”

At Invasion Day rallies and similar anticolonial actions, Jews Against Fascism can be found organizing a Jewish bloc of protesters. “We are acutely aware of the political reality of white supremacy on stolen land: if there is an escape from white supremacy, it is through decolonisation, however that might be identified by Aboriginal communities. But also many of us grew up politically through the teaching, leadership, writing, and generosity of some of the most staunch and wonderful Indigenous activists. The lessons we learnt – the length and breadth of these lessons – are central to our activism.”

~

Where do we go from here?

As I peeled back layers of collective mythology with every conversation, and started to grapple with much more complicated histories of Jewish antifascism, Zionism, and relations with Indigenous peoples, the work of building our shared futures came into view — and each community organizer and researcher I spoke with has an idea of what the future holds. David Zyngier tells me that anti-fascist activists in Melbourne will continue to come together as needed, outnumbering fascists 3:1. Zac Roberts believes that Jewish communities doing the listening, recognising our position as settlers and tending to our interpersonal relationships with Aboriginal people will enable us to cultivate more reciprocal relations. Having left the AJDS, Max Kaiser and Jordy Silverstein are working with others on starting a new Jewish group in Melbourne. As well as screening her documentary and sparking generative dialogue, Kea Cranko is working with Vivienne Porszolt to organise Jewish community in Sydney. Jews Against Fascism are starting to see Jewish lefties on the margins come together to build community, to fight, to create a Jewishness for ourselves that struggles against assimilation, to build relationships and solidarity in our communities. To which I say, chazak chazak v’nitzchazek.

Our personal, political and spiritual pasts are bound up in our futures; we can’t talk about one without the other. We can never extract ourselves from the pasts we look to, but when we come together to tend to our imperfect histories, and unravel the myths we tell ourselves about how we got here, our shared futures begin to reveal themselves to us — and they’re more compelling than anything I could have imagined on my own. I’ll meet you there.

~

This piece was developed across the Wurundjeri lands of the Kulin Nation, and the Gadigal and Darug lands of the Eora Nation. As I expand my knowledge of my own cultures and histories, I pay respect to the knowledge embedded forever within Aboriginal custodianship of Country. Though routers connect us to URLs and the world wide web, we too are tethered to the land, and the colonial present. I acknowledge all sovereign nations this article may reach. Always was, always will be.

Mika Benesh was a 2021 Resilient Writing Fellow with New Voices Magazine and the Institute for Jewish Spirituality.