The final article of a two-part series on SCWANA and Balkan Jewish stories of adornment. Read Part One, “Most Decorated Women”, here.

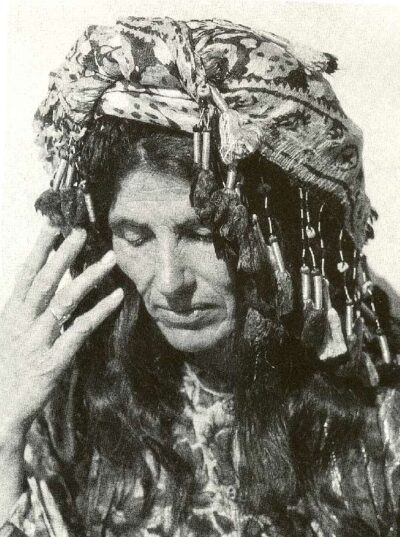

In every corner of Jewish collective memory, I found earrings. In some grandmothers’ cabinets, I found bowls lightly stained by henna. Under their sleeves and on their faces, I saw scars from where they tried to burn off their tattoos with acid. Most of all, I saw them adorned by their yahadut – their Jewishness. I wanted to know everything about them and their decorated lives, from the mechanics of glittering brooches to the names of the patterns in a Bukharian bride’s headscarf.

I also wanted to hear more perspectives on tattooing, including stricter ones, to understand the prohibition. I reached out to Luna Skye, Sefaradi scholar and cellist. She took a Socratic approach to understanding the contexts and histories of the adornments mentioned in my previous article.

Skye wrote that tattoos are definitely a prohibition, and taken seriously in Jewish histories and presents. “Tattoos in modern Western culture around us largely don’t reflect those same associations of religious worship, but there’s still a prohibition. Miṣwot aren’t predicated on the ṭa’am [taste, feeling]; the ṭa’am is what you’re potentially supposed to get out of doing it. What it’s meant to transmit or inculcate.” Skye clarified that “The ṭa’am [with regards to tattooing prohibition] relates to ‘avodah zarah and the sanctity of one’s body.” Skye also felt strongly about marit ‘ayin and how it is used to intra- and extra-communally police followers of Sefaradic thought.

“Also on the flip side, while tattoos are clearly assur [prohibited] – it’s the act of getting one that’s assur. Once it’s there, it’s there – and I think it’s important not to shun people for it (which definitely happens, sadly),” wrote Skye. This evoked past concerns of forcibly tattooed Shoah survivors who were anxious about whether or not they would be permitted a Jewish burial.

“There are specific things prohibited on the basis of marit ha’ayin. But nowhere does it say ‘it’s assur to do something that might be marit ha’ayin,’” concluded Skye. Kurdish temporary tattoos were in; non-tattooed harqus, on hands or face, was fine. In the cases of Frenchmen wandering through the Maghreb and Walter Fischel bumbling into Kurdistan, ‘appearance to the eye’ meant almost nothing at all. French men visiting the Maghreb rarely asked for enough information from their Jewish women subjects, and Fischel missed golden opportunities to ask Kurdish Jewish women for clarification on their temporary tattoos, albeit in his shaky Aramaic. Jewish stories, it seems, tend to contain far more than the external – even if that’s where our ornamentation stops.

– – – – – – –

In the days during and following the above interviews, people began reaching out to share their stories. I also contacted people I knew personally. One of them was Bat-Anat, an Amazigh-Sefaradi Jewish friend.

Portugal, Algeria, and Morocco are all a part of Bat-Anat’s family story. Her great grandfather migrated from North Africa to the United States in the early 1900s and was taken in by a white family. His son, Bat-Anat’s grandfather, was resentful of his father for not passing on his Jewish and North African heritage to his children. He felt that the process of assimilation had cheated him out of his heritage – and he was sad because he couldn’t pass on that heritage to his own children. In his later years, he and Bat-Anat grew close, and he told her everything he knew. I loved the pictures of Bat-Anat in which she wears her street clothes with traditional jewellery.

It was her grandfather who encouraged her to dig in and learn more. She feels that revitalizing and reclaiming her heritages is tremendously important. “I’m very big on de-assimilation and assertion of cultural identity in the face of colonial and homogenized society. It’s a difficult process because it can be hard to find resources or traditional practitioners of certain things.”

“I didn’t grow up with henna or harqus directly practiced, but I recall mention of some of my ancestors and relatives in the 19th century using henna as hair dye,” she said. Bat-Anat’s henna and harqus practices exist in her family as temporary dyes in the context of both daily and celebratory ornamentation. She reconnects with them as a way of embodying her ancestors. She takes pieces of herself and her histories back from a dominant culture that seeks to replace them with absence.

Bat-Anat is also an out, intersex lesbian. She identifies with Sarah Imeinu as a historical, intersex Jewish woman. In particular, she cited Yevamot 64b:2:

אמר רב נחמן אמר רבה בר אבוה שרה אמנו אילונית היתה שנאמר (בראשית יא, ל) ותהי שרי עקרה אין לה ולד אפי’ בית ולד אין לה

Rav Naḥman said that Rabba bar Avuh said: Our mother Sarah was initially a sexually underdeveloped woman [aylonit], as it is stated: “And Sarah was barren; she had no child” (Genesis 11:30). The superfluous words: “She had no child,” indicate that she did not have even a place, i.e., a womb, for a child.

“Jews have always lived on the fringe of what is considered mainstream,” she said. “We’ve always questioned what’s considered universal. When I practice, I embrace that variance. I remember that HaZaL [Ḥakhameinu Zikhronam Livrakhah, “Our Sages, May their Memory Be Blessed”], even in ancient times, recognized my identity as more valid than European or American society ever has.” In other words, while Sarah Imeinu briefly did not have a place for a child, HaZaL always had a place for a woman like Bat-Anat: – intersex, henna-wearing, and irrefutably Jewish.

– – – – – – –

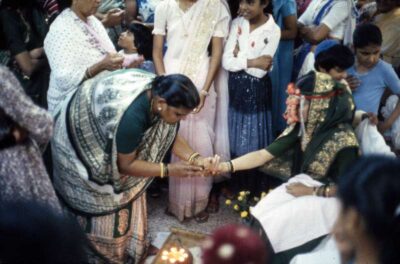

Esther, a Tunisian Jewish woman currently residing in France, shared the stories of the women in her family with me. “My grandmother always loved henna and used it,” she wrote. “Either on her hair or hands. She always taught me that we should rejoice for Shabbat, and henna is an expression of that joy.

“So every Friday morning, just like she used to do, I put some henna on my hand. Nothing fancy, just a small circle in my left hand as a reminder and symbol of joy.”

Esther sent me a picture of herself at her graduation. She looks beautiful. Her hand, decorated with a winding, jet-black floral motif, peeks out of her robe’s sleeve. “The black thing along my hand – that’s harqus,” she writes. “In Sfax, we call it naqsh.”

She told me more about her memories of her family, especially her grandmother, in Tunisia. “The house never closed. Women used to open the door and stay in the kitchen, and talk all day long. And every Friday morning, we go to the hammam [bathhouse in Islamic majority lands].”

I had seen old pictures of women in my Balkan family who used henna in multiple styles. For daily wear, it was used as nail polish; or, the finger was dyed with henna until the second knuckle; and often, but especially for important events, a circle was made in the center of the palm. It felt good to know I wasn’t the only young woman who wanted to normalize wearing it, including in professional contexts. There was something about the circle that was complete, holy, and round.

I have dreamed of a weekly henna practice in relation to Shabbat for a long time. There was something even more powerful about it being in the center of the palm as well as on the fingers, which I associated with life cycle events such as weddings and engagement parties. At these events, a coin is often tied on top of the henna with a red ribbon. I wanted to marry Shabbat every week, and use henna to mark the occasion. Two brides, wedded for life: Shabbat, and me.

– – – – – – –

וָאֶתֵּ֥ן נֶ֙זֶם֙ עַל־אַפֵּ֔ךְ וַעֲגִילִ֖ים עַל־אָזְנָ֑יִךְ וַעֲטֶ֥רֶת תִּפְאֶ֖רֶת בְּרֹאשֵֽׁךְ׃

Wā-etein nezem ‘al-apeikh wa-’agilim ‘al-āznākh wa’aṭereṯ tifereṯ brosheikh:

I put a ring in your nose, and earrings in your ears, and a splendid crown on your head. (Yeḥezḳel 16:12)

The customs, halakhic rulings, and visual cultures of SCWANA and Balkan Jews are deemed to be insufficient and disorganized by Ashkenazim and the non-Jewish world. In Ashkenazi contexts, a Jewish person has to be Reform, Conservative, or Orthodox – and even within these broader categories, there are smaller and increasingly specific movements to align oneself with. In classical SCWANA and Balkan Jewish communities, one space holds both secular and religious Jews. In some ways, the plurality of SCWANA, Balkan, and Ethiopian Jewish communities is also perceived as a threat to the potential for Jewish “unity” and a justification for Orientalizing antisemitism that gentile Europeans directed at Ashkenazi Jews.

Via my research, I was also able to finally release the baggage I carried with me for so long regarding my own cultural decorations. Many of my fathers’ familial traditions had been dismissed by outsiders as overly indulgent and materialistic, but I find our visual culture far from shallow, especially in modern contexts. For my LGBTQ+ Jewish friends, many of whom “flag” by wearing nose rings and earrings, I pulled together the textual threads of Leviticus to weave a new picture. For example, piercing one ear to flag is not at all outside of the scope of Jewish behavior, including for a man.

I was continually intrigued by the gendered dimensions of permissible piercing. English-language Jewish sources distinguished “Jewish” and “non-Jewish” sites of piercing, namely describing Rivḳah’s nose piercing as “the custom at that time”; describing piercing as woman-exclusive when Jewish textual sources did not distinguish either piercing as gendered, nor nose-rings as un-Jewish; or likening them to a rite of passage. I pictured my sixth-birthday ear piercing again, remembering my joy and nervous excitement. I wanted that for every Jewish person.

I continue to seek out the narratives and memories people have of their material cultures. Understandings of Judaism, love, and holiness are forged in the adornments we wear. We are linked together by a chain of memories, experiences, and relationships that tether our communities to one another – and to communities that are not Jewish, by tenuous strands of fibrous tissue that continue to grow. The sooner we all consider our stories as interrelated, bound up in all of one anothers’, the sooner we may come to terms with their truths and pains, working toward a world of peace, justice, and truth.

– – – – – – –

Here is a brief reading list, courtesy of Dr. Noam Sienna.

The use of indigo and turmeric as a body adornment was described by Erich Brauer in his 1947 ethnographic study of Kurdish Jews (published posthumously), Yehudei Kurdistan: mehqar etnologi. This book was also republished in English translation in 1993 by WSU Press. The reference to indigo and turmeric is on page 137 of the Hebrew original. It is describing a ceremony for welcoming a newborn child, often called sheshe (from Hebrew shishi, “the sixth [night]”) which was practiced by a number of Jewish communities across Central Asia. In Iraq and Iran, they used saffron rather than turmeric, and in India they used henna.

The references for those are:

David Sassoon, A History of the Jews in Baghdad (1949), pg. 182

Mavis Hyman, Jews of the Raj (1995), pg. 110

Leah Baer, “Life’s Events: Birth, Bar Mitzvah, Weddings, and Burial Customs,” in Esther’s Children: A Portrait of Iranian Jewry (2002), 314-315 — and cf. the essay by Haideh Sahim on personal adornment, “Seven Steps to Beauty,” in the same anthology

Shirley Berry Isenberg, India’s Bene Israel, 129

____________________________________

This article is the second part of a two-part series on SCWANA and Balkan Jewish adornment. You can read the first part here. The featured photo is a collage with imagery courtesy of the Israel Museum. Mirushe Zylali was a 2021 Resilient Writing Fellow with New Voices Magazine and the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. Featured photos courtesy of the Jewish Museum.