וַיְהִ֗י כַּאֲשֶׁ֨ר כִּלּ֤וּ הַגְּמַלִּים֙ לִשְׁתּ֔וֹת וַיִּקַּ֤ח הָאִישׁ֙ נֶ֣זֶם זָהָ֔ב בֶּ֖קַע מִשְׁקָל֑וֹ וּשְׁנֵ֤י צְמִידִים֙ עַל־יָדֶ֔יהָ עֲשָׂרָ֥ה זָהָ֖ב מִשְׁקָלָֽם׃

Wayhi ka-asher kilu hagmalim lishtoṯ, wayaḳiḥ ha-ish zāhāv beḳ’a mishḳālo ushnei ṣmiḏim ‘al-yaḏeihā ‘asārāh zāhāv mishḳālām:

When the camels had finished drinking, the man took a gold nose-ring weighing a half-shekel, and two gold bands for her arms, ten shekels in weight. (B’reishit 24:23)

“I can tell you a story,” said Rabbi Tsipporah “Tsipi” Gabbai.

Nearly a hundred years ago, Ḥaninah walked through the market in Boujad, a small city at the feet of the Atlas Mountains. At fifteen years old, she was pretty, kind, and especially loved by her brother, David. She also caught the eye of a Muslim man in the market, who admired her beauty. She repeatedly refused his propositions. A few days later, on a subsequent visit to the market, a car pulled up beside Ḥaninah. A man grabbed her and pulled her inside. Before anyone could help her, the car disappeared into the distance.

Boujad in the earlier half of the 20th century was home to 30,000 Jews, Muslims, and a few Christians; it was unique in that it did not have a melaḥ, the segregated Jewish quarter that was a fixture in most Moroccan cities. People of all faiths and tribes lived in Boujad shoulder-to-shoulder. Just as different-faith communities living side by side was ordinary, so were frequent kidnappings of Jewish women by Muslim men – including Rabbi Gabai’s aunt, Ḥaninah.

“Her brother David was devastated. He spent eight years looking for her. He thought he could find her, because she couldn’t have children – so maybe that would make the guy more willing to let her go,” said Rabbi Gabai. Eight years after Ḥaninah’s kidnapping, David had not only become a rabbi, but a businessman as well. After years of searching for her, he paid a Muslim man to reunite with Ḥaninah. They met in a cemetery after dark. When Ḥaninah lifted her burqah, Rabbi David could see that she was crying. He could also see that her face was covered in tattoos. “One of the first things they did to Jewish women when they took them in Morocco, even if they wanted to become Muslims, they tattooed their faces, like to say ‘For life, you are not a Jew anymore.’” Because Ḥaninah was unable to have children, her captors begrudgingly released her to Rabbi David. Ḥaninah returned home around the time that Rabbi Gabai’s mother was born.

“Some of my early memories, I can remember her screaming. She was trying to burn off the tattoos with acid. I remember it as a little girl because it was, like, supposed to be a shame. If someone were to take a picture of her, back then, they would say ‘Oh, this is a Jewish woman.’ But they wouldn’t know her story.”

French men, Jewish and gentile, traipsed through the Maghreb in the early 20th century, photographing Orientalized subjects. A century later, their minimally-labeled photos remain enshrined in museums, the voices of women and girls, including tattooed ones, insufficiently captured by them. Women like Ḥaninah were being shot, but not with a gun.

– – – – – – –

My interest in tattooing and piercing in Jewish cultures originates in my childhood. My biggest takeaway from my fleeting interactions with my Jewish family’s religious practice was that the body re-enters the earth the way it “came out” of it, precluding tattoos and – so I thought – piercings. As I connected with Judaism, my desire to understand halakhah surrounding adornment increased. I became interested in the communities that seemed to fuse both of my family’s cultures, my father’s side being Muslim: Jews from South, Central, and West Asia; North Africa; and the Balkans.

I was drawn to the digital archives of the Israel Museum and the Jewish Museum. There I found pictures of “tattooed” women, nose rings from South Asia, and heavy earrings from Morocco and Afghanistan, among other beautifully preserved objects that comprise global Jewish visual cultures. I also looked into writing by Walter Fischel, an Ashkenazi visitor to 1940s Jewish Kurdistan:

I had never seen a more picturesque or impressive mourning assembly. Such Jews! Men virile and wild-looking; women wearing embroidered turbans, earrings, bracelets, even nose-rings, and with symbols tattooed into their faces—our brethren and sisters!

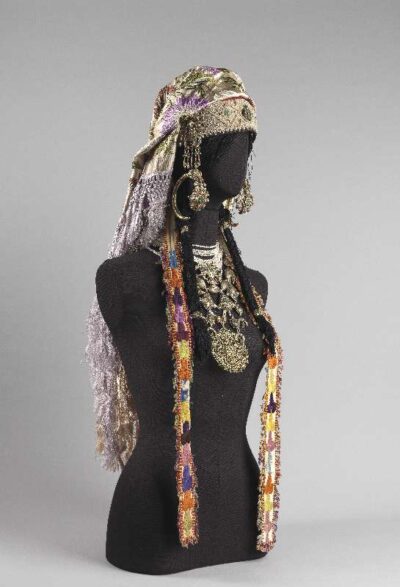

I was not only frustrated by Fischel’s failure to consult the Kurdish women about which he wrote, but inconsistencies in the museums’ online labels. Any picture of a woman with facial markings did not mention whether she was Jewish. A woman wearing earrings that Rabbi Gabai called khoras k’bash (rams’ horns) was not marked as Jewish, but a similar style of earring featured in a reconstruction of the wedding ensemble of urban Jewish brides in Morocco.

I didn’t have access to the writings of Jean Besancenot, the French man who had taken all of the pictures in the Israel Museum’s archives. I wondered whether he, unlike Fischel, had taken the time to listen to women’s explanations about their clothing and customs. On other sites mentioning the photographer, he was described as an essential piece of historical understanding of Moroccan Jewish traditions. The word used for the black markings seen on the skin of women is “harqus,” spelled by French-speakers as “harkous.” Rabbi Gabai told me that, to her knowledge, Jews in the Maghreb did not use it. Rabbi Gabai is the first female Moroccan rabbi. She is a spiritual leader, storyteller, and community activist, allying herself closely with issues of LGBT+ rights. I was honored that she was sharing with me.

“I have no idea,” said Rabbi Gabai. “I know, in North Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, I know for sure that it was very forbidden to have tattoos. Not even for decorations – like when you did henna on the forehead for henna decorations, maybe, but eh, so I don’t know.” Rabbi Gabai also told me that, while nose rings were rarely, if ever, worn by Moroccan Jewish women, they have never been forbidden by Jewish law. “Halakhically, you can see the example of Eli’ezer, the servant of Avraham, who is given earrings to find a wife for Yitzhak, in the whole Levant, or for Jacob who gives it to Rachel. We have examples of women wearing the nezemim [Heb. nose rings, masc. pl.], no prohibition in doing that. In my opinion, nothing is forbidden about putting earrings in your ears,” she said.

Rabbi Gabai compared the piercing of her daughters’ ears at a young age to a b’rit millah. “We are connecting,” she explained, “everyone to our history – to our ancestor, to Judaism, all that.” I smiled at the thought of my ears – pierced at Claire’s as my dad held back tears – as a type of b’rit, and ancestral connection with women who came before me. The earrings were not a gash, and the tattooing – whether subdermal or under the skin should not have excluded a Jewish woman from her community.

“It was never her fault,” affirmed Rabbi Gabai of her aunt Ḥaninah’s kidnapping. “She was a child. Living in these countries, there was some good, and some bad. Some good people, some bad people.”

– – – – – – –

Seeking more clarity about harqus and tattooing, I came across the blog “Eshkol Hakofer” written by Dr. Noam Sienna. While no longer active, it is a blog about Jewish henna and other body markings in Jewish (and sometimes non-Jewish) communities. Sienna is the author of A Rainbow Thread, an anthology about LGBTQ+ Jews in history. I found this quote from his article about harqus, and another about body art in the Maghreb and Kurdistan (also known as Ezidistan; Shabakistan; Assyria; Mesopotamia):

But how can we tell if a given design is done in ḥarqus or a tattoo? While there are plenty of beautiful patterns, there is almost no way of knowing for sure whether it is a tattoo… Except in one circumstance, of course: photographs of Jews! (2015)

While Kurdish Jews did not tattoo themselves, they did use indigo (nila) and turmeric (zaira) to create temporary body art, especially for ceremonial occasions such as a child’s birth (Brauer 1947: 137), another custom also practiced by other Jewish communities in Central and South Asia. (2014)

“People like Fischel are seeing a few things,” Sienna explained via video chat. “They’re seeing body decorations, but the only body decorations they’re familiar with are tattooing. They don’t bother to, or can’t, ask the people they’re observing. So intentionally and unintentionally, they’re traveling to these places and creating and working within narratives shaped by Orientalism. For these visitors in these regions – it may seem logical to conflate all types of body decoration. But they’re not interchangeable.” What had piqued my interest was that Fischel had specifically referred to tattoos into the skin of Jewish women. Now I knew they were not subdermal.

Dr. Sienna stated that Jewish communities’ ornaments are always painted, and always in conversation with their Muslim and non-Muslim neighbors. They often dressed very similarly. “In some cases, there is a real distinctiveness that separates Jewish and non-Jewish communities visually. In other contexts, it’s just that we don’t need to worry. It’s obvious [that they’re Jews].” Dr. Sienna felt that the past is equally as important for understanding Jewish visual signaling. “There’s an inherited set of norms, whether that’s etiquette, where you live, or who you’re with. Within these contexts, there’s no worry or confusion that they [Jews] are gonna look like Muslims. Everyone knows who’s Muslim and who’s Jewish.”

“I met a really old man in a moshav in Israel, who was from a Kurdish village called Sindur,” said Dr. Sienna. “He was from a community of Kurdish Jews who were Arabic-speaking. He brought a keffiyeh with him from Kurdistan, and I saw a picture of him in it. He folded it up into a neat square and kept it in his closet for decades. The risk of being conflated with the ‘enemy’ was too high,” he concluded, referring to Israel’s numerous wars with neighboring, Arab-majority countries.

– – – – – – –

וְשֶׂ֣רֶט לָנֶ֗פֶשׁ לֹ֤א תִתְּנוּ֙ בִּבְשַׂרְכֶ֔ם וּכְתֹ֣בֶת קַֽעֲקַ֔ע לֹ֥א תִתְּנ֖וּ בָּכֶ֑ם אֲנִ֖י יְהוָֽה׃

Wisereṭ lānefesh lo ṯitnu bivsarkhem ukhtoveṯ ḳ’aḳ’a lo ṯitnu bākhem ani ADONAI:

You shall not make gashes in your flesh for the dead, or incise any marks on yourselves: I am the LORD. (Wayiḳra 19:28)

Seeking to better understand the halakhic ideas I internalized from the Jewish spaces in which I grew up, I contacted Binya Koatz. Poet, leader, and activist, Koatz is one of the founders of Trans Girl Talmud. She shared with me that the hazy concept I remembered from my childhood – non-Jews mistaking Jewish behaviors as contradictory to Jewish laws and texts – called “marit ‘ayin” (appearance to the eye).

“These are all bubbe meises,” she said. “This idea that your body has to go into the earth the exact way it came out. If you have a life saving surgery and an organ removed, your body isn’t re-entering the same way. If you get your ears pierced, eventually, that’s a permanent hole.” Those words – going out of this world as you came into it – were ones I heard before.

“Marit ‘ayin is like tzniut. It’s something that some people, some classes within Jewishness, are allowed to ignore for convenience while it’s simultaneously, more often, used to control women.” Ṣniut (here in a spelling used by some Sefaradi, Mizrahi, and Balkan Jewish communities), more commonly spelled tzniut or tznius, refers to ideals of modesty, and is associated especially with Orthodox Jewish communities.

The rule of not mixing poultry with dairy came about because Jewish religious authorities were concerned that poultry was being mistaken for meat by non-Jews; a concern for marit ‘ayin. The same logic may be the origin of the prohibition on tattooing: a Jewish person being mistaken for a member of a non-Jewish tribe, or a pagan group.

“You just can’t do these things [tattooing] in the name of other Gods. It comes about within a context of ‘avodah zarah.” ‘Avodah zarah, or “foreign servitude/work”, refers to the worship of gods that were not the Israelite God. ‘Avodah zarah also refers to worshipping God in unsanctioned ways.

I thought about Jewish people from South, Central, and West Asia, North Africa, and the Balkans who had moved to Israel. Some were from cultures like Rabbi Gabai’s, in which henna and earrings are normalized; others, from Kurdistan and South Asia, in which nose rings were common. With Koatz, I speculated that these adornments had a racializing impact on these Jewish groups. Instead of henna and piercings being recognized as Jewish adornments with Jewish textual histories, they were seen by the Israeli government, overwhelmingly dominated by Ashkenazi Jews, as evidence of these Jewish communities belonging to other nations. An intra-communal ethnocentric canard about SCWANA (South, Central, West Asian, North African) and Balkan Jewish people having dual loyalties developed.

I asked Koatz what she thought reclaiming these adornments might mean. “We would have to fill in the cracks of our own cultures instead of replacing our cultures with the vacantness of Euro-American consumerist cultures,” replied Koatz. “Not expressing ourselves based on what we like to consume, but what we want to create – what we do. Not the brand name of what we drink or wear.” On a practical level, this would mean uncomfortable moments in which our own aesthetic tastes would butt up against expectations of respectability, assimilation, and professionalism. My mom has often told me not to normalize my henna usage because an American employer might find it inappropriate for work.

In Wayiḳra, women and their children, regardless of gender, wore earrings.

וַיֹּ֤אמֶר אֲלֵהֶם֙ אַהֲרֹ֔ן פָּֽרְקוּ֙ נִזְמֵ֣י הַזָּהָ֔ב אֲשֶׁר֙ בְּאָזְנֵ֣י נְשֵׁיכֶ֔ם בְּנֵיכֶ֖ם וּבְנֹתֵיכֶ֑ם וְהָבִ֖יאוּ אֵלָֽי׃

Wayomer Elohim Aharon parḳu nizmei hazāhāv asher b-āznei n’shikhem bneikhem uvneoṯeikhem w’hāviu eilāi:

[Aharon] said to them, “Take off the gold rings that are on the ears of your wives, your sons, and your daughters, and bring them to me.” (Shemot 32:20)

“As for tattoos,” continued Koatz, “there’s a history of Jewish people, even in our texts, getting tattoos – etching Yod Hei Vav Hei – into their skin. I think it’s not only okay, but holy if it’s done out of love for our God. The tattoo just has to be really Jewish.” The prohibition on tattooing comes from Wayiḳra 19.28 (Parashat Ḳedushim), which is printed above. With regards to the concept of marit ‘ayin, “It [marit ‘ayin] really bars queer Jews from Jewishness in the eyes, sometimes, of other Jews and the world. It bars Sefaradi Jews from Jewishness in many contexts. It’s just not Jewish, from any angle, to judge someone from the external.”

“We don’t act or dress for non-Jewish people so that they will think we’re Jewish, we live for the Torah and Hashem.” Koatz imagined a different future for what it means to be a visible Jew. “You can tell someone’s Jewish because of how they act, and also because of how they look. I want people to be visibly Jewish as well – but with more signifiers than the normative ones that have been created.”

Marit ‘ayin can bar people from certain Jewish spaces, but those same people can also adhere to and take marit ‘ayin into consideration in their own communities. For example, some of the behaviors of Masorti (traditional; in the US ‘conservative’) Sefaradi Jews could be perceived as violating halakhah in the view of masorti Ashkenazi Jews (soft matzah or riding bicycles on Yom Tov). In this case, concerns about marit ‘ayin look different for Sefaradi and Ashkenazi Jews on an intra-communal and extra-communal level. However, Sefaradi Jews should not be beholden to that Ashkenazi gaze, just as Ashkenazi Jews aren’t beholden to a non-Jewish gaze.

The refusal of Tanakhic women to hand over their own adornments and the adornments of their children was a refusal to give up their principles – their newfound Jewishness and nationhood – in the face of assimilating into a wider culture of worshipping idols. Women and their children of every gender stood firm in their belief in Jews as an emerging nation. Refusing to give up beauty, art, love, and adornment, especially in the name of God, is, in fact, a declaration of loyalty and trust. In this case, the women of Israel both looked Jewish and behaved Jewishly.

In the understandings and memories of Rabbi Gabai and Koatz, there is also no firm divide between the adornment practices before the Ten Commandments and after. The gash described the Ten Commandments never applied to earrings and nose rings, and would never apply to our matriarchs Rivḳah and Raḥel, as I had also mistakenly thought.

– – – – – – –

I reflected on what people suffered through or left behind as they existed in the world as themselves, or tried to take on new identities – American, Israeli, French, Moroccan. My father’s side of the family are Balkan Muslims. Facial ornaments, today attached most often via eyelash glue, were more common over twenty years ago. My mom often talks about how my Muslim grandmother’s attempts to include more traditional clothing items (facial jewelry [sequins, coins, floral pieces], hair tinsel) into wedding-clothes were rebuffed. They were brushed off as “primitive” – better left in the village. By the time my mother had jeweled the skin above her eyebrow, Americanized cousins told her to remove the silver leaves. Burning in me was the desire to wear all of my cultural clothes. They were embarrassing and an inconvenience to Americanness, so they were left behind. Now, they are reappearing steadily on Instagram accounts devoted to Balkan and Turkish wedding fashion.

My mind also went to Jewish South Asia, where women wore beautiful, bejeweled nose rings in daily life. When Jews (namely Bene Israel and Cochin communities) moved to the cities, their nose rings fell out of use. I wondered why, but did not yet have anyone to ask. Whether or not traditions develop or exist depends on the choices of the people to whom those traditions belong. South Asian Jewish marriage pendants were created under the auspices of Hindu smiths, to be worn as one of many necklaces on the bride’s wedding day. I relished that someone chose to document these pieces of information, included as a part of the provenance of each piece. Really, the provenance of anything is the long memory of the bequeather.

I deeply valued the inclusion of narratives that defied ideas about what it means to be a Jewish person which, globally, tends to signify a white, Ashkenazi person. Caring about the narratives of the entire Jewish world means caring about stories often perceived as shameful or that contradict ideas about how Jews dress; what they eat; what they speak. While we are a large nation, we are far more diverse than any of us knows, and there is nothing about our rich tapestry of visual cultures that should be left behind for the sake of a streamlined narrative.

Since childhood, I had a hazy concept of the prohibition on tattooing being related to signifying whether or not one was Jewish – for example, able to be buried in a Jewish cemetery. I also believed that, in Jewish law, ear piercing and tattooing were equivalent as permanent gashes. Along the way, I had picked up the idea that a Jewish person existed in only one cultural context in which they wouldn’t be mistaken for non-Jews. In the charged political atmosphere after both 9/11 and the Second Intifada, I had internalized that my father’s culture was, and must be, mutually exclusive with my mother’s, and vice versa, lest I be mistaken…for whom?

My own enemy?

That is not my birthright. Real or perceived, any enemy can also become a friend, neighbor, and shared community member. We are, in fact, a constellation of communities all bleeding into one another, in the same way that the ocean floor runs into the sand of the shore. In this new world, we must all be each other’s keepers – of safety, memory, and tradition. While I was now well on my way to learning as much as I could about the adornments of Jewish women around the world in history, I had new questions to answer. I knew exactly who I would ask, and braced myself, like a time traveler, for my rapid catch-up to my peoples’ present.

Read part two of this series on SCWANA and Balkan Jewish adornment here. Mirushe Zylali was a 2021 Resilient Writing Fellow with New Voices Magazine and the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. Featured photos courtesy of the Jewish Museum.