South, Itokaga.

It is hot out, the dusty ground is warm under my feet and my shirt sticks to me with sweat. I am going to see my grandfather in between dances. Under the canopy of branches it is hot and quiet and smells like clean sweat. I can look up and see the sky between the cracks in the ceiling. My grandpa is tired, he is reclining on a mat on the ground. When he sees me he extends his tired arms and I arrange myself in his lap. He has a few cuts on his upper arm, which I try to poke at with my dirty hands. He brushes me away gently. I ask how he got those cuts, curious, and also knowing that the wise child is one who asks about the symbols behind things. At 6 years old I am already trying to understand the relationship between my Jewish self and the Lakota practices I have been welcomed into.

He explains it’s a part of the dance, a way he’s praying to Wakan Tanka, the great spirit. The next day I am allowed to watch as two men make little notches in my grandpa’s arm. The removed flesh is tied up in some cloth. He is bleeding and sweat goes into his cuts, but he looks very peaceful. My mom is next, and she cries a little from pain when they cut her, but she explains to me that all we really have to offer to Wakan Tanka was our own selves, our own bodies.

The way most westerners talk about ceremonies like this one is primitive and disparaging. They use words like “savage” and “brutal”. They say the ceremony is meant to “appease the Lakota God”. When Jews talk about the old ways of praying at the temple, the ways of animal sacrifice, they often adopt a similar language and attitude. By the tone most people take up, I feel I am meant to be grateful that we have now been enlightened to a cleaner, more sophisticated way of communicating with Hashem. For those who have never witnessed how sacred such a way of praying can be, it feels obvious that sacrifice, pain, blood, and smoke are bad ways to pray.

As I’m getting to know myself better, I’m coming to the understanding that I only exist within the relationship between my Lakota practices and my Jewish practices. In fact, I only exist within my relationships, period; my sense of myself is held in the tensions between my desires and in my relationships with human and non-human planet-mates. When I try to pick one piece of myself up to examine and describe it, it fades into shadow and refuses to be seen. I’m searching for a sense of wholeness, and I’m starting to suspect that an objective self that can be easily described will never exist for me.

West, Wiyokpiyata.

John (Fire) Lame Deer was a Lakota spiritual leader and healer, who wrote about his first Haŋblečeya, commonly referred to as a Vision Quest. He describes the flesh sacrifice made to create the sacred tools he would take with him to the vision pit. “In [the gourd] were forty small squares of flesh which my grandmother had cut from her arm with a razor blade. … Someone dear to me had undergone pain, given me something of herself, part of her body, to help me pray and make me strong-hearted. How could I be afraid with so many people – living and dead – helping me?”

When I told one of my Jewish mentors I was working on this piece she asked, “When you pray the Lakota way, do you feel like you’re praying to the same God?”

This question terrifies me the way little children are afraid of monsters in their closets. I have no idea how to answer it and freeze up. I tie my tongue into a knot, untie, and tie it back tighter as I try to answer without calling myself a pagan or a polytheist or an illogical rock worshiper, all things I have been called when I try to be too honest with the wrong people. Instead of engaging with the person sitting across from me who cares about me and trusting her to hold the wholeness of me, I back away and fall into a familiar pattern of judging myself harshly.

From Fred R. Gustafson’s book “Dancing Between Two Worlds”, on the subject of whether or not spirits exist: “The resistance [to using the word spirits] seems to involve an attitude in the western world that is driven to find answers to everything and to distrust that which we cannot see or explain. It involves a collective need to both literalize and personalize the soul … The end result is often a detached indifference on the one hand or a literalized fundamentalism on the other.” When people try to talk about God, we can often get trapped by the temptation to take language literally and end up feeling like we can accurately describe the nature of the universe in English. This can make us feel powerful and important, but it can also curb our sense of curiosity about the things we can’t understand or explain.

Speaking myself aloud means speaking in a language of distinctions, thus also speaking myself into distinctions. Even in this article, I have made a distinction between Wakan Tanka, the great spirit I pray to with the sacred pipe, and Hashem, the king of the universe who I pray to when I say modeh ani. In words that don’t exist, I know that these two names are brought together through the relationship they share when I pray to them.

Once, before I was born, my Grandpa Fred was asked if he believed in spirits. My grandfather was a Lutheran minister and a sundancer and a Jungian analyst. He eventually replied that he did, but didn’t know how they manifested themselves. I believe in a greater power, I believe in oneness with the earth and with everything on it, I believe in medicine, I believe in Torah. I believe in Hashem, I believe in Wakan Tanka, I believe in spirits, and I do not know how any of these manifest themselves.

Maybe this reluctance around describing my ideas about God’s presentation comes from the same root as my confusion about my own manifestation(s). I carry a multiplicity of identities. As a result of the expansive love of my mother and the people she invited into my life, I was given three names in my first three months of life. An English name the day I was born. A Hebrew name eight days later. A Lakota name in my third month of life, as my godfather held me beneath the Sundance tree. Triply identified, I wore a badge of queerness before I could raise my own head on my neck. As an adult I have chosen two new names, reflecting my gender transition. If I am made in Hashem’s image, why wouldn’t I imagine a God with all the same inconsistencies and multiplicities as me?

White supremacy culture privileges one white way of being and punishes or tries to exterminate all other ways of being. To that end, it seeks to separate us from each other, from the divine, and even from our own selves by segmenting us into distinct and warring factions. Because I am made of the relationships between things, white supremacy has also pitted parts of myself against each other, demanding that I make a choice between my spirit and my body and between one way of praying and another.

North, Waziyata.

The Sundance ceremony requires the use of a tree in the middle of the circle. This tree carries prayer ties and supports the dancers. In order to have a tree at the center of a clearing, a tree must be cut down and moved. This is its own ceremony, one I only attended a few times in my childhood. The first ax cut is made, then many more ax cuts. I don’t remember all the details, I must have been only 10 years old. But I remember singing to the tree, and I remember when the tree is felled we gather chips from the ground and hold them to our lips and thank the tree for its life and its sacrifice and thank Wakan Tanka for giving us this way to pray.

At Jewish day school, my Hebrew teacher gave us the rules for treating a book that had Hashem’s name printed out. If you drop the book, press your lips to it. Don’t put your feet on a table that has the book on it. Don’t put the book on the floor. I took it seriously, very seriously, and I still do. I believe the book has a spirit, as I believe all things have a spirit, especially because this book is a book I use to pray and because this book came from a tree that lived a life before it was cut down. The tree made a sacrifice so that I could carry this book in my arms and learn my ancestor’s way to pray. When I sing in Tefillah I cradle a siddur in my hands even when I know the words to the prayers by heart. Why? Because the siddur is important on its own. It is a part of my ancestors’ ways, and it is a reminder that kol haneshama tehalel ya (Psalm 150), that all that has breath shall praise Hashem.

East, Wioheumpata.

At the end of the ceremonies, camp is broken. We put our tents back in the car. The tree is felled a second time. But the circle remains, dug into the dirt from days and days of dancing feet. Next year, we’ll return to this circle.

In America, many Jews have grown comfortable in our synagogue buildings, with their prescribed spaces for socializing, for praying, for teaching and learning, for play. Without the building we would be forced to confront our bodies: our needs for bathrooms, food, ample seating, microphones, quiet space to rest. The doors of the building also give us the ability to police the bodies that enter our space.

I belong to communities with buildings and communities without, and I have to admit I like having a dedicated Jewish space. Knowing there is a building in my town where I can seek shelter has been psychologically lifesaving. During periods when I didn’t feel safe at home, my synagogue was one of the only places I could sleep a dreamless sleep, and I did so as often as I could, curling up on the youth directors couch in between classes. But even so, my community’s dependence on physical buildings has limited our collective imagination.

I don’t trust our feet to carve out space for us, don’t trust the earth to hold onto the impressions of our footprints. After centuries of wandering, it feels good to rest on a cold tiled floor nestled between our brick and stone walls, to walk through the world carrying the key to this place that shelters our vulnerable Jewishness.

I’m tired of rending myself from myself in order to be accepted. My mother likes to say that Tikkun Olam is about returning the world to its original state of wholeness. I believe in order for the world to be whole we have to be explicit about the interconnectedness of all things: inside our own selves, between each other, and between ourselves and our non-human planet-mates. My starting place in this work is to create a whole self that encompasses all the parts of my life and experience, even the ones that defy description.

“Ein Beit Midrash bli chiddush”, says an old saying. There is no house of learning without innovation. A call to inner expansive wholeness is not chiddush; people wiser than me have been sounding this call for many generations now, but there is space for us all.

At Jewish overnight camp, we prayed outside. After years of spending Tefillah quietly settled between a thin carpet, a plush seat with hard armrests that separated me from my neighbors and a high wood ceiling, praying on benches outside felt like falling in love for the first time. Suddenly davening made sense. My hips and elbows pressed playfully against my friends, while splinters, wind, birds, trees, and so many bugs participated gladly in the service. I was alive, I was in relationship with the world around me.

I close my eyes and breathe. The breath that I breathe came from a tree. I give my outbreath back to the trees. Kol haneshama tehalel ya. The tree and I breathe together, and we pray together.

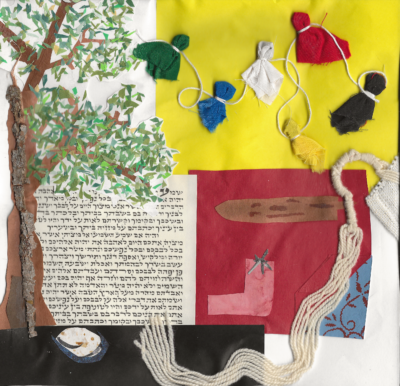

The featured image for this piece is a collage created by the author. Samuel Elijah Rose was a 2021 Resilient Writing Fellow with New Voices and the Institute for Jewish Spirituality.