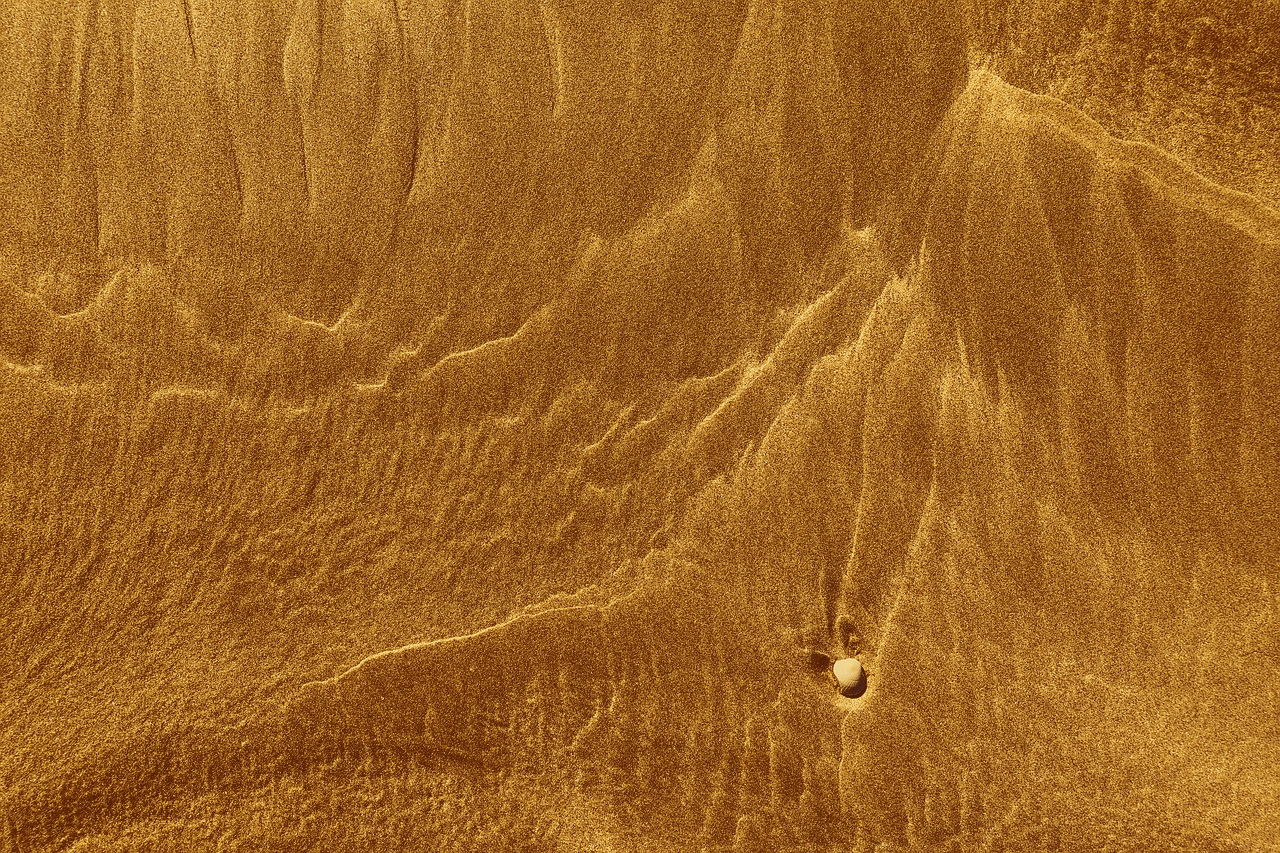

“These thoughts are like quicksand,” I told a friend one night, the words a tether to rationality, a self-addressed postcard from some place of frustration, lost in a loop of thinking. What I meant was this: out of nowhere they are liable to grab me, and then in an instant the ground below gives way. The thoughts hold fast to my ankles, and then my legs begin to sink, and then I am stuck. It isn’t always this dramatic, but the metaphor holds.

Figurative quicksand and I have a history: I live with obsessive-compulsive disorder. In periods of unwellness, unsettlingly violent thoughts fester in my mind for stretches that feel interminable. Obsessions are all-consuming, quicksand in the analogy. Compulsions are one reaction to this wave of panic, the instinctual urge to assume some semblance of control. They are utterly ineffective, not to mention embarrassing, time-consuming, and challenging to resist. I often compare the experience to itching a rash: you know it is a bad idea, and that thirty seconds of relief is not worth prolonging your discomfort. At the same time, you ask, how long am I willing to wait for it to resolve? What’s the worst that could happen if I scratch just this once?

As a practicing Jew, OCD has at times complicated how I navigate my Jewish identity. Waves of graphic images of Jesus, bleeding to death and gasping for air in the final moments of his life have become a fixture of my experience in recent years. I imagine myself completing the sign of the cross while phrases of Christian prayers or New Testament verses play on loop in my head for hours at a time, for weeks or months on end. At the grocery store, I become terrified that merely noticing an advertisement for bacon is a sign that Judaism is not the path for me. My eyes notice cross-shaped patterns in window panes and floor tiling while a corner of my mind hums its tired lyrics: What if Jesus really is God? What if, someday, I convert to Christianity? Maybe I just haven’t uncovered this piece of my true self yet. Maybe the shift has already occurred. That would explain why I can’t stop thinking about it.

Learning to manage OCD has grown less difficult overtime, but I don’t know if it will ever be easy. Increasing my capacity and resolve to choose refraining from the false security of compulsive ritual is continuous, uphill work. What helped me learn to embrace that challenge – in addition to receiving outside support and prioritizing other daily health choices such as sleep – was internalizing the fact that a person’s thoughts are not indicative of their character. Even so, this knowledge is no air-tight defense. OCD remains stigmatized, and the decision to reveal one’s experience can be particularly fraught for those whose symptoms center on taboo topics. It is one thing to suggest that the content of our thoughts is irrelevant in principle; it’s another matter to see how subject material becomes a heavyweight factor as we interact with our social identities and communities.

Although images of Jesus no longer hamper my ability to participate in life or occupy more than a few minutes of my day, they continue to inspire feelings of shame and secrecy. Accepting the presence of recurrent thoughts about Jesus is, technically speaking, the same task as accepting the presence of recurrent doubts over whether or not I turned off the stove. Practically speaking, it feels as if the two tasks have little in common. Of the myriad topics my OCD has centered upon, none rivals the level of shame and distress stemming from the thoughts about Jesus and Christianity. It’s hard to describe the pain this has caused, in part because the effect was so pervasive, and in part because doing so requires admitting the extent to which my relationships to God, Torah, and Jewish tradition—forces I had previously understood as the most consistent and foundational in my life—were so quickly shaken.

In the beginning, I knew that I was anxious and that “Jewish ritual” helped me feel better. What problem could there possibly be? But soon the line between sincere mitzvot and spiraling patterns of irrational compulsions became near impossible for me to distinguish. It was then I realized this course was unsustainable.

Internal uncertainties about my legitimacy as a Jew in the face of these unfamiliar thoughts were a constant burden. Jewish events, community gatherings, and private engagement with Torah study and regular prayer grew increasingly difficult to tolerate. There is a difference between genuine ritual approached from a place of desire or commitment, and deceptive ritual, carried out from a place of fear. Compulsive actions masquerading as religious practices are not mitzvot [religious commandments]; if anything, they are the antithesis. To my untrained eye, the two categories shared the same external form. I never knew if I was engaging in religious practice or performing harmful compulsions under that guise, and so the thought of participating in any kind of Jewish practice grew to be too much to face.

In the truest sense of the phrase, nothing was sacred anymore. How could aspects of the tradition I understood as life-giving possibly be harming me? Before Whom did I stand when my relation to God was stretched so taut that I feared it could snap? Where could I turn when the spaces, people, and rituals that had long been a source of strength and comfort become a continuous reminder of my most acute pain?

As I began to learn about my condition and take on the work of adjusting my habits and patterns, against the compassionate advice of others and my own better inclination, I assumed that it was best to go it alone. I withdrew from my Jewish community because I felt embarrassed and afraid of the prospect that mitzvot which felt intrinsic to Judaism might be compromising my health. Everything trickled to a standstill: I stopped attending synagogue and Torah study classes regularly, I stopped observing many of my usual shabbat customs. I stopped reciting the sh’ma at night because I couldn’t stand the urge to repeat it eighteen times if I imagined Jesus as I chanted the Hebrew words, which I always did. I cried myself to sleep instead.

Avoiding Judaism didn’t help me feel better; frankly, it was also compulsive, and therefore detrimental. But I did need a break before I could relearn how to engage in honest Jewish practice without feeding a force that could destroy me. I did not know how to explain the confusion I felt without actually explaining the confusion I felt, and so I reached an impasse. Although I informed a select few of my OCD in general terms, the “Jesus thoughts” stayed near to my chest. This was a loneliness I compounded voluntarily. Despite irrational anxieties that I could be labeled a fraudulent Jew, there remained legitimate concern that my spiritual integrity might be questioned were I to reveal this piece of myself. Keeping quiet, although exhausting, was at the time less painful than thinking up contingency plans to save face should I ever be treated poorly as the result of another’s misinformation or ignorance.

Recently, I have wondered whether my Jewish practice and theology (mediated, necessarily, through my experience of OCD) could ever be understood through a lens not built atop this internal challenge, thought pitched against thought. I never defined “faith” as the inverse of doubt. Judaism is a tradition where questions are important and healthy. The process of rebuilding my Judaism as a prerequisite to living healthfully with OCD was the very thing that allowed me to reclaim the importance of Judaism in my life. There is nothing as Jewish as a theology rooted jointly in the senses of exile and hope, in constant struggle with God and oneself. This path is one of doubt and blessing, amidst the chaos it is peace.

I am both thankful and deeply aware of how lucky I am to be in a healthier position at present, in relation to both Judaism and OCD. Lately, I have cultivated a sense of reverence for a few basic facts: OCD is, was, and will be a part of my experience that I ought to avoid ignoring, lest it quickly worsen. I feel increasingly comfortable living with and in myself, leaning on others for encouragement, and allowing myself to be supported. Now that I am able to speak with greater openness about OCD with some in my closest circles, I can see how the stigma I internalize holds me back to a degree that is at minimum equivalent to, if not more consequential than, the stigmas I observe externally.

Let me be clear: I am not embarrassed or ashamed to have OCD. There is no trace of wrongdoing or sin in my condition and its effects. I have done nothing to inherit this circumstance and there is nothing I can do to make it vanish outright. And so, it is greatly healing to view the journey of grappling with the impacts of OCD—specifically, the journey of working through its relationship to my Judaism and my own self-stigmas—through a lens of teshuvah. In invoking this term, I reference not repentance, but return and answer. (The questions might be: What am I afraid of? What are my responsibilities? How can I be of service?) Teshuvah is a return to confidence in my engagement with tradition, it is a repairing of the judgement with which I occasionally greet myself, it is a commitment to honor and celebrate the improbable strength and courage I draw upon daily, to render it a renewable resource rather than a lucky find. My links to God and Torah depend entirely on this perspective of forgiveness and compassion, and perhaps my life does, too.

The Torah of OCD is simple: it is an important and very serious mitzvah to manage my OCD as skillfully as I am able on any given day, seeking out the support and resources I need to live well and in good health.

And it is deeply complicated: I am no longer comfortable theologizing pain. Over the past several years, I rarely questioned the reality of God, but my ideas about what kind of God I relate to have changed. When OCD began to target my religious identity and observance, the notion of identifying God as either a root of or remedy for such overwhelm quickly began to sound cruel. I cannot accept any system in which God is connected to its cause or components, and still all of my hope rests in the idea that God is evenly present throughout its course. I am commanded to acknowledge the inevitability of difficult days, and my ability to endure them, as symbols of strength. It is upon me to refuse complicity in despair, to recognize God’s presence in every instance I resist a compulsion, and to see this same presence and love in occasions where I find myself laboring for hours over an empty ritual or perseverating on a thought. All of it is okay. God is in every day I keep going despite an endless buffeting of frightening thoughts, every occasion I access hope or, better yet, can be a source of hope for someone else.

There is a lot of talk about the need to build awareness and visibility to break the stigma around mental illness, and these efforts are noble. But here is a secret: no amount of external discussion can stand in for the importance of feeling empowered in our own experiences and by our own resiliency. This piece aims to be educational, to describe the actuality of OCD to those who may not be familiar. It is written for anyone who has struggled and knows this Torah innately, to show them that they are not alone. Knowing that we exist, even in anonymity, is revelation for its own sake.

In the depths of my narrowness, I regularly debated the merits of speaking to a rabbi or other mentor about what I was living through. Not to look for reassurance, or pity, or sympathy. Not to look for advice or validation. Only to tell someone who might grasp how agonizing it was to have my world flipped upside down, to let them know how it weighed on me, to explain why I had stopped attending Torah class. I wanted to share my new ideas about Shabbat and halakha, to walk them through the growth and change I had wrenched from misery. I wanted to weep and lament, and then spring up to dance and cry hot, salt-laden tears of joy. I wanted to hear, from someone I respected and who respected me, that all of the things I loved and missed and grieved over about Judaism would be there for me once I was well enough to make this teshuvah, to go back to the core of myself with a heart at once smashed to pieces and overflowing. I needed to hear that neither my mind nor my Torah were broken. I haven’t been able to drum up that bravery. But I now know this much to be true for myself; my mind and my Torah are not broken, and neither are yours, and this is enough.

One of my favorite holidays is Tisha b’Av, a day of fasting and mourning at the height of summer. In synagogue, we read the book of Lamentations, a brutal take on the destruction of Jerusalem and the First Temple. I don’t derive gladness from any of this, but I find it to be amongst the holiest and most affirming days of the year. Tisha b’Av grants us the ritual and liturgical space to grapple with the fear that everything that brings us towards fulfillment may be gone forever. It permits us to question if we’ve lost access to God, if our lives will ever feel recognizable again, if we will be comforted, if someone will bear witness to our pain. We feel our hurt fully and do not run away. We ask, not at all rhetorically: what is left for us to hold on to when the pieces that have mattered most are not only missing, but seemingly turned against us? Healthy grief does not negate the joy we feel over where we are, our gratitude for the places we have arrived.

OCD sometimes does feel like a banishment from the things I care most deeply about. Still, continuing to see the possibility of God as a central figure in my life following the most severe feelings of distance is the bravest and most resilient thing I can do. I find solace in the recognition that my thoughts are equal parts scary and sacred. Their power is at times profound, yet it is not enough to render my connection to Judaism obsolete. I may never understand how to make sense of this nonsensical reality, how to be a Jew like this. But I am.

The day after I likened my intrusive thoughts to quicksand, I learned something new about real-life quicksand: it is not lethal. We cannot drown in it; the density of the human body is too low. Sink as far the waist and the air in our lungs will keep us afloat. Struggling to get out only worsens the predicament. Escape is both logical and counter-intuitive: leaning backwards to increase the surface area of our body allows the upper extremities to float while keeping our lower limbs from sinking too deep into the abyss. Slowly wiggling our toes, ankles, and knees creates space for water to seep in, making it easier for the legs to rise up to the surface. We must remain calm and patient to break free, but quicksand alone does not kill. We are designed to float when descending rapidly. Thank God for that.