“Someday you will be special but // you will wear no special marking.”

I remember where I was when I read that line for the first time. The echo of its feeling still hits me as I transcribe it here. This is the last line of a poem from “Timtum: A Trans Jew Zine” by Micah Bazant, a publication famed and hallowed among those who know it.

I’d spent the afternoon with a couple friends at Quimby’s, a bookstore that has been described as ‘the internet before there was the internet’ and sells more zines than possibly anywhere else on the planet. As a suburban Chicago Jew, Quimby’s became a haven throughout high school of the edgy, the weird, the queer; things that were realer and more beautiful than I’d yet known. A trip down to Quimby’s was a Sunday afternoon-long affair; you had to sit in the store for at least three hours, combing through the vast ephemera of zines to make sure you didn’t miss the ones that were created just for you. It’s fun to judge zines by their covers, by their shapes and binding. There’s a lot of digging involved. I remember a friend coming up to me holding an old-looking zine, one that looked like it had been xeroxed in a game of printed telephone, in the old style. “I think this one is yours.”

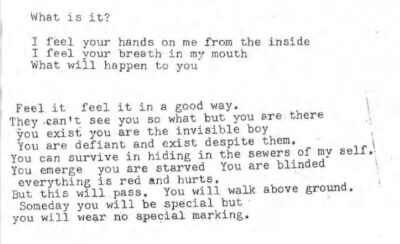

The iconic cover of Timtum seared into me immediately: Micah Bazant’s forlorn or wistful horned Jew sewing and snipping their starred, scarred chest underneath the Hebraic lettering of a term they’d resuscitated from the Talmud, from the Yiddish, and into an entirely new-old life that was the first word I ever found to really, in my wholeness, describe me. “Timtum: a sexy, smart, creative, productive Jewish genderqueer.” This was Torah.

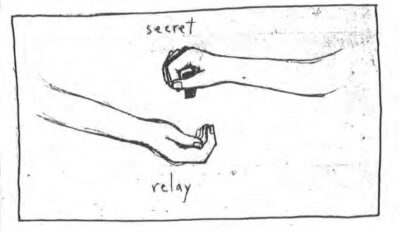

I don’t believe the fatalistic old adage that all things happen for a reason, but I do believe that there is meaning to be found in everything. It doesn’t feel like a coincidence that Timtum ended up in my hands at that moment, my senior year of high school, when I was having both my Jewish and gender awakenings concurrently, exploring both shabbat observance and my own faggotry, agonizing more and more with each day that it wasn’t possible that the Jewish world I sought could ever have a place for me. Innovation often comes with isolation and I was too new to be understood. Then, suddenly, Timtum appeared in my hands and told me, by its very existence, that not only was I not alone, but part of a cherished, underground tradition, passing a secret package between each generation, smuggled in our coats and beneath our clothes, with “parts so dangerous and large that they were sometimes unknown to the smugglers themselves.”

“But now it has landed here, with me, in North America,” Micah wrote in 5760, over twenty years ago, “I don’t know when my family was last free to be openly and fully Jewish. Most Jews never were. I feel a responsibility to the generations who sustained this, who died and lived as Jews – who am I to throw away this most precious of gifts – now, when I am finally free to fully unwrap it?”

With every page of Timtum, I internalized the life-saving, redemption-making truth that there is no experience more Jewish than exile.

Though the sentiment feels dark, it contained a light I hadn’t seen before. Up until that moment, I had thought that my genderqueerness was fundamentally incompatible with my people. I was illegible to my own tradition, and the paradox of my own identity drove me into a spiritual existential angst only exacerbated by being seventeen. But here was Micah, with their strange and beautiful drawings and time-bending writing, telling me that I was perfectly in place. The sense of alienation I felt at the hands of my gender was itself a Jewish experience. There was no contradiction. The medicine was in the wound.

The Baal Shem Tov says that the worst galut, the worst exile, is when one doesn’t know that they’re in exile at all. The gift of the trans Jew is that they know just how far in galut we really are. I promise, that awareness is revelatory.

These days I feel lucky to be alive at a Jewish moment where institutions like Svara are flourishing, where brilliant teachers like Laynie Solomon and Joy Ladin teach our communities, where I could help raise queer campers as an out-and-trans counselor at my childhood Jewish summer camp, where trans Torah is being revealed at light-speed, with revelatory and liberatory sparks for all of us, collectively, as the Jewish people. I feel lucky to be alive at a moment where I inherited Timtum at the bottom of a pile in Quimby’s bookstore.

When I hold my copy of Timtum, which remains on my bookshelf next to signed copy of “Souls on Fire” by Elie Weisel and “The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions” by Larry Mitchell, I can feel the heat of white fire, the part of Torah that we reveal beyond the written word. If my house were burning, this zine would be one of the first things I would save.

Timtum saved me and somehow, was saved for me. It moved me to the point of creation, hoping to pay forward for the next generation of nice Jewish queers and faygelehs and timtums and jewfags and rootless cosmopolitans and cultural marxists and those yet unborn or still unknowing who they are. I wrote my own trans Jewish zine, “House of Jacob // People Israel” because Timtum had given me a modality to speak: the Rabbis wrote commentaries and we write zines. Micah Bazant’s iconic artwork finds its way into places that surprise me, comfort me when I see those familiar lines. The images often float without citation, but conjure Jewish ghosts that remind me who I am every time they appear.

So I end this love letter to Timtum on the sixth night of Hanukka knowing that this zine is exactly like the candlelight: a proud, Jewish thing that brings warmth and light into the world’s heaviest darkness. I revisit it every year, and I love the way it makes the faces of other Jews more beautiful in the glow.

Read more about Jewish zines and find the other Hanukkah Jewish zine features by visiting our holiday landing page here.