When it became clear earlier this year that I would spend the summer at home, my mother invited me to join her for a ten-week clay sculpture class taught by her counselor, Alan. My mother picked Alan from the counselors in our area because she saw his photo on the internet and thought that he “looked like a rabbi.” That my mother, who grew up in a reform, mostly Ashkenazi, Jewish community in Florida, would identify a white, bearded elder as such is not terribly surprising, though after meeting Alan it was difficult to imagine him as a rabbi. Spry and bow-legged, Alan bounced among the picnic tables of our outdoor classroom, leading us in playful activities replete with cardboard props, taking us on hikes through the surrounding forest to commune with trees and listen to the birds. Perhaps more rabbis would benefit from bringing Alan’s playfulness into their communities, but Alan himself more readily embodies his former profession: kindergarten teacher.

We met each week in the recreation area beside the public pool in Putney, Vermont, the next town over from my hometown, Brattleboro. The area’s distanced picnic tables sat beneath a metal awning, a space that I imagine would have been cluttered with floaty-adorned children and popsicle wrappers any other summer. The pool was empty. Some weeks, greenish rainwater gathered in the deep end where metal ladders, descending into emptiness, ended far from the empty concrete bottom, a sharp drop down. One week, we arrived to find that a compact nest had grown on the top rung of the shallow end ladder, a submerged impossibility any other summer. It almost felt as if we could leave our supplies there each week and they would still be there the next, as if we were the park’s only visitors. We may well have been, but we still carried our own 25 lb bags of clay to and from the car each class, bringing along our own cardboard boxes and plastic packaging to cushion our weekly creations during their ride home with us.

More than once, my mother and I went home after our class and argued— about the unacknowledged, appropriated indigenous stories that Alan often used to give our class shape, the meaning of classmates’ comments or the quality of their work, Alan’s Jewishness (and our own). In this pandemic summer, our class was a welcome diversion from our daily fears and worries, and it often felt like a relief to have something new to discuss, to be reminded of the world beyond our kitchen table and the increasingly tragic stories reaching us through our phones.

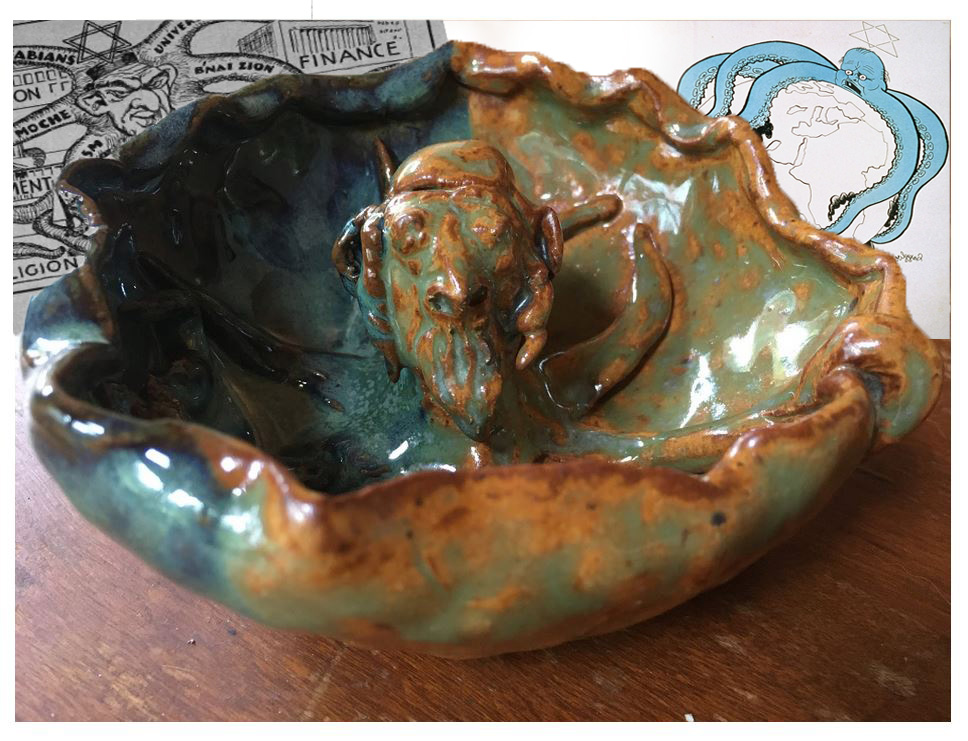

Most weeks, Alan began our class with a meditative activity: the gentle sculpting of pinch pots with our eyes closed. Alan calls them “blessing” or “beloved bowls,” inviting us to envision loved ones as we pulled the bowls’ rims out of the core of balled clay. One week, Alan also began our class with a culturally-unidentified creation story about a grandparent figure, prompting my mother to sculpt the face of her step-grandfather, a white Jew from Florida. Alan’s classes are fast-paced, and we quickly shifted to another activity, setting our first pieces aside as we responded to a different text. Somehow, my mother ended up with three pieces: her bowl, the face, and a sprawling sun. As he often did, Alan then encouraged us to combine elements of our pieces, to let our creative energy guide us to completion; My mother brought together her beloved bowl and the grandfatherly face and some sun’s rays to create, in the end, what appeared to be an octopus with her Jewish step-grandfather’s face, tentacles dripping over the bowl’s rim.

When I looked over to her half of our picnic table, I immediately started laughing at what I thought was its obvious provocativeness. We didn’t talk about it on the way home, but I sent a picture to one of my friends, who agreed it was hilarious, and so antisemitic, but like, in a funny way.

But that night, my mother awoke with the sudden concern that she had done something unforgivable. The next morning, she asked me if I thought it was antisemitic too, and when I laughingly told her yes and also that I thought it was kind of amazing, she didn’t share my amusement. At her counseling session with Alan that afternoon, she asked him if he had concerns about the bowl, and reported back that he seemed mostly unfazed, instead wanting to refocus her attention on her own creativity, and on creating art without too much self-judgment. For Alan, sculpting is about impulse, broad forms, acceptance of one’s creations as they come to be. One week, noticing that I was struggling with his prompts, Alan encouraged me to work at a larger scale, to engage my entire hand in the sculpting instead of just my finger tips, to allow the greater impulse of the piece to come into being. For Alan, there was no perfection. There either was something tangible or there was not. He extended this understanding to my mother’s piece, emphasizing not her concerns about its possible (mis)interpretations but instead its worthiness as something created by her.

The bowl revived a long-running disagreement between my mother and me about Jewishness, antisemitism, and humor. What I found funny and subversive about the piece, my mother found horrifying. Though my mother will always identify as Jewish, it is not to Judaism that she turns when she is looking for spiritual guidance, and, like more reform Jews of her generation than anyone really talks about, her Jewish practice is secular. We paid membership dues to our local Jewish community until just after my bat mitzvah, and then we stopped. This detachment from Jewish ritual, however, does not leave her insensitive to its portrayal.

A similar argument ensued after our family watched the Coen brothers’ film, “A Serious Man,” which my mother found so antisemitic that she stayed up late googling reviews that agreed with her to prove her point. I thought the movie was very funny, and very Jewish. In particular, my mother criticized the film’s depiction of its protagonist’s rabbis, who are depicted as hilariously incapable of offering the kind of guidance or wisdom that one might seek from a rabbi or communal leader. My mother, who has rarely turned to a rabbi for guidance of any kind, who felt dismissed and misunderstood when Jewish leadership in our community refused to officiate her marriage to my non-Jewish father, who wanted a counselor who looked like a rabbi but not a real rabbi to guide her, worried that the film’s fictional rabbis would somehow reveal the ineptitude of Jewish leadership to masses of antisemites poised to believe in a falsely pious Judaism.

It does not matter to my mother that the Coen brothers are Jews— she believes their work an undiscerning invitation to antisemitism. My mother’s position is roughly that Jews should not make jokes or device humorous fictions that could be understood by the non-Jew or antisemite as evidence for antisemitic tropes. She does not trust the audience to be benevolent. She worries that the art’s creators, though they claim to be self-aware, are not actually in on the joke. And to be clear, for my mother, the joke is that Jews are not safe from other people.

Beyond humor, our disagreement compounds my mother’s concerns about my anti-Zionist creative projects and activism. She worries less about my opposition to Zionism (my mother is herself not a Zionist, and is mostly ambivalent about Israel) than that discord in the Jewish community might expose Jews to more antisemitism from non-Jews. She thinks it’s probably safer to support an institutional Jewish American party line that we both struggle to identify with than to publicly criticize it. That the present options are intentionally limited by organized initiatives to exclude and consolidate power is not lost on her, but far be it from her to do anything about it. This is just the way things are, so please don’t make self-effacing art (or, God-forbid, write an op-ed) about it. My mother’s conception of Jewishness is in constant contrast with a non-Jewish “they.” When pressed, she says that the “they” she imagines is white, like we are.

My mother knows that I am writing a piece about what she calls “the ashtray,” and she texted some thoughts about her work: “If you make something and you didn’t mean for it to be antisemitic, is it antisemitic? Should it be destroyed? Because that thing is going to outlive me. And people in the future could see it and think whoever made it must be antisemitic. So it makes me wonder if I should bury it.” I try to imagine this proposed burial, the false ceremony of it. What prayers might we say for the retraction of misguided art? What is the blessing for burying our shame?

To focus too much on the triangulation of Jewishness among Alan, my mother, and myself risks missing a broader story of our clay class, which was larger than the three of us and offered the kind of cohort that is exceeding rare during the on-going disasters of the pandemic. But at least in regard to my mother’s bowl, our mutual consideration of the piece was animated by our shared and divergent Jewishnesses, what we might be able to decide, collectively or otherwise, about the piece’s humor, danger, innocuousness, tone. At the risk of publicly invoking Jewish humor (sorry, Mom), we were three Jews with four or more opinions, and we came to no consensus.

The night of our last class, we unloaded our glazed pieces from the kiln, passing each piece hand-to-hand between us from the kiln shelves to our class display table, where all of our finished pieces awaited one final appraisal before our cohort parted ways. Our glazing session two weeks before had been a frantic evening of dipping and dunking, with most of the class using the same half-dozen or so glazes in similar ways. But it is the way of glazing that things come out unpredictably, and so, though many of the glazed pieces resembled each other in color, some stood out. My mother’s octopus bowl, half a layered greenish blue, half yellow pooled with green, was one of the most strikingly colorful, the glaze animating the octopus legs, now half in water and half on dry land, evolving. Our classmates admired it, Alan held it up for closer inspection. But on the drive home, my mother told me she didn’t want it, that she couldn’t bear the confusion of looking at it, of trying to decide what it meant to her, what it might mean to others. She told me that I could keep it if I wanted. I said yes.

All of this is what my mother has given to me. Now I need to figure out what I’m going to do with it. ⋄