Midway through the summer of 2020, the Editor of New Voices Magazine received an envelope in the mail they hadn’t remembered ordering. The enclosed publication was colorful and brightly printed, with Yiddish, English, and Cyrillic across the cover. An avid zine collector with special attention for queer and Jewish content, “Kolektiv Goluboy Vagon: Issue 01, May 2020” was unmistakably sent to the correct address. Filled with recollections and expressions of post-Soviet, queer Jewish narrative from across the United States and Canada, this almost scrapbook-style publication, with each page a different hue, unfolds in layers of story and image reckoning with sharp edges of diaspora.

Deeply moved by the zine, our Editor set off to learn about the artists and writers behind the Kolektiv. In this interview, New Voices connected with Kolektiv Goluboy Vagon members Sophia Sobko and Stepha Velednitsky in a wide-ranging conversation about the zinemaking process, assimilation and de-assimiliation, the intersections of post-Soviet Jewish queer identity, and building a transformative diasporic future.

Who and what is Kolektiv Goluboy Vagon?

Sophia: We are a cultural and educational project – collective of about thirty 1.5 and 2nd generation post-Soviet Jewish immigrants living in the U.S. and Canada who identify as queer and/or trans, and gender marginalized. Right now we are all white and Ashkenazi, which means we do not represent the whole post-Soviet Jewish diaspora.

We meet live, virtually twice a month: once a month there is a “structured / на обед” session on a relevant topic co-facilitated by kolektiv members (e.g. ritual practice, trauma and healing, Palestine, whiteness and the Movement for Black Lives, etc.), and once a month there is an “unstructured / на чай” drop in time when people can just show up to catch up, propose a discussion topic, etc.

I started the group in October 2019 as part of my PhD project, organizing bi-monthly group sessions on Zoom (pre-COVID!) that were co-facilitated by kolektiv members. Since then we have worked toward building shared leadership and recently launched our committee of 7 members. We are trying to make this work sustainable, strategic, and responsive. I take inspiration from adrienne marie brown, and in the spirit of Emergent Strategy think of us as one “fractal” – always trying to show up with integrity and deepen our relationships toward collective liberation.

How did the idea for a Kolektiv Goluboy Vagon zine come about; how did the project start? How did it grow?

Sophia: Most of our work is dialogical, ephemeral. From the beginning of our meeting, many of us had a desire to create a cultural product, some kind of trace of our conversations, our meaning-making. Most of our work has also been internal; since October 2019 we have been mirroring one another, validating each others’ experiences. I would say that we have always been each others’ primary audience, but the zine was also a chance for us to share with our broader communities the parts of ourselves that had thus far been invisibilized (for many of us, at least). It also felt like a very important chance to speak against colonialism and white supremacy from our particular historical position.

I think many people brought up the idea of making a zine over the months, but at the end of our first “season” of meetings, Rebecca and I invited other members of the kolektiv to submit entries. The “call” itself was very simple and broad – there was no prompt. One of our members, Irina, got us into a show at the Chicago Cultural Center – “In Flux: Chicago Artists and Immigration” and 6018North provided us with funding to print zines. We were originally planning a small in-person zine launch, but then COVID hit. With the zine launch moving online, we quickly realized that our audience may be larger and more diverse than we had expected. Some of us contributed to a collective statement of our politics for the zine and the launch event. This was the first semi-formal declaration of who we are and what we are trying to do. The launch itself was incredible – well-attended and impactful for both us and many audience members of various backgrounds and positionalities.

There are all sorts of available media for talking about identity and Jewish experiences. I was wondering, why make a zine? What drew you to the zine format?

Sophia: We are scrappy. I have been stewarding the kolektiv as part of my PhD work. A zine seemed like an accessible and doable format for a group that does not have too many formal resources, funding sources, etc. It was also a way to get as many people to participate as possible with a pretty low entry bar (do something on a page), though of course when the time came, filling a page was much more intimidating than it at first seemed. We were also drawn to the Soviet tradition/practice of samizdat – self-publishing. I am careful not to appropriate the term uncritically because we are not writing from a context of state censorship or hiding (though many of us are not out to our families). At the same time, it’s incredible to think that our ancestors have been self-publishing – whether in the context of Soviet censorship, Russian and Soviet anti-Semitism, or even here in the U.S. While working on the zine, Judy and I magically discovered that our grandparents had worked together to publish a book of Soviet Jewish war veteran memoirs! I am still learning the benefits and possibilities of the zine. Just yesterday I was going to meet my cousin and was relieved and excited to realize that the zine could show her this cultural work better than I could ever explain it.

Kolectiv Goluboy Vagon’s zine centers the experiences of queer post-soviet Jews living in the United States. How do you feel that being a post-soviet Jew influences your queerness, and vice versa?

Sophia: This is such a good question, one that I’m sure the different kolektiv members would have different answers to, and something I am still figuring out for myself. Queerness to me is a radical politic, a breaking of boundaries – what Cathy Cohen called “a political orientation of radical transformation, rather than assimilation into existing systems.” Via this definition, my post-Soviet Jewishness absolutely informs my queerness – specifically through the ways I (and many of us) were positioned as “other” in relation to hegemonic American whiteness, American Jewish Ashkenormativity, etc (groups/spaces/positions we seemingly belonged to, but which also felt different from). This dissonance/distance in my years as a young immigrant caused tension, pain and anger that, over decades, has led to a strong desire to resist oppressive categories and constructs, rather than assimilate. Whereas people of color are not given a choice — they are always read as other/foreign/non-white — I was given a ticket to assimilation, and I want to resist it with every ounce of my being. My queerness, via both my politics and sexuality, is definitely part of that.

How does my queerness conversely inform my identity as a post-Soviet Jew? Well, I am a “bad” post-Soviet Jewish immigrant. As someone assigned female at birth, I am supposed to be feminine (even if a post-Soviet version of feminine, which is not the same as American), marry a cis man, have kids, and get a well-paying high-status job with which I can support my parents as they age. Instead, I date a woman, I don’t have kids, don’t have a stable career, and like to spend my time fighting racial capitalism and making art. This is the stuff of many immigrant parents’ greatest fears. Or, as one friend and kolektiv member said, “I am my ancestors’ wildest nightmares.”

In our group we fight shame and “being bad”-ness. I think it’s wildly beautiful that my queerness opens up the possibility of radical and transformative futures for post-Soviet Jewish diaspora. I honor my ancestors’ and parents’ struggles, resilience and dreams by pursuing my own – something they never could have imagined – and probably wouldn’t have wanted to.

Stepha: There are a lot of aspects of traditional post-Soviet gender relations that are queer to North Americans. Matrifocal (if not matriarchal) social structures, expectations of women’s professional excellence in technical fields, the ways we raise our voices in affirming one another’s enthusiasm or outrage or love when we talk to one another — these are just a few examples of the ways that post-Soviet people enter queerly into American society.

My family of origin is also pretty queer, even by post-Soviet standards — my grandmother once told me she’d probably have married a woman if she was born into my generation; my mother uses masculine-gendered pronouns when describing herself. When you’re part of a small immigrant community, it’s hard not to extrapolate the experiences of your immediate family to your culture of origin at large — this is why it’s so hard to become estranged from your family, because they are also your cultural connection. Given the nature of my gender position and my upbringing, it was very easy to step into a queer identity — by American standards, my family and I had been queer all along.

My queerness troubles my post-Soviet Jewish belonging to the extent that I view it as a broader political orientation — against capitalism, extractive industrial and social relations, assimilation into a white supremacist racial regime, nuclear family structure, and the settler colonial delusion that land can be owned, let alone purchased. It’s hard to create a life for yourself that disappoints your family’s hopes of assimilation and accumulation, but that’s what queerness has meant for me as an immigrant.

Experiences of marginality among American Jews appear a lot in the zine; what do you wish that the non-soviet American Jewish community understood about your experiences?

Sophia: Ha, that’s our anger. Some of us have long articulated that, while others (including myself) have only recently come to consciousness about the ways we have silenced ourselves/been silenced, invisibilized ourselves/been invisibilized. For those of us who are white, those are the particularities of both passing as a white American Jew and hailing from a completely different place, language, history, etc. Many of us are ambivalent on this question. Some of us say the zine was made for us, we are our own primary audience, and we couldn’t care less what others know or understand. Others are excited to share more of themselves with broader audiences.

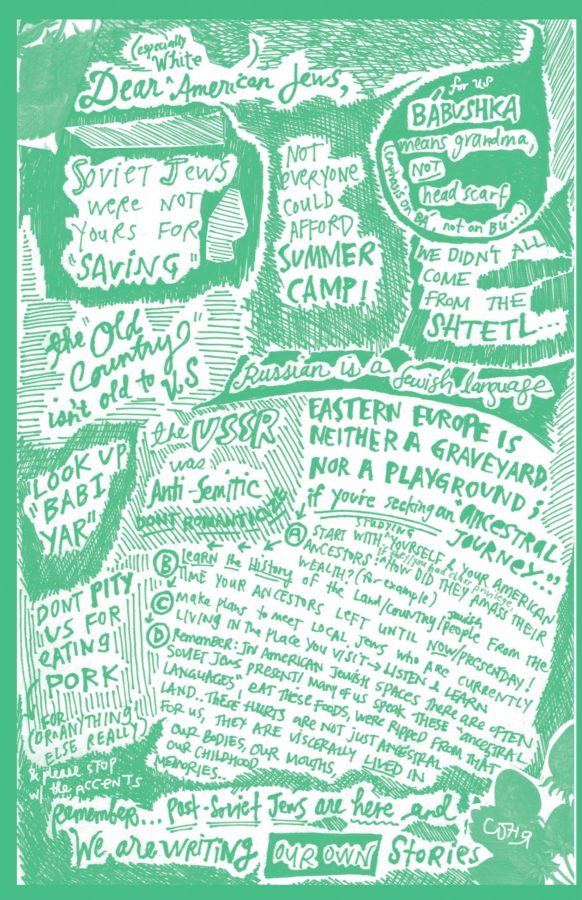

At the same time, I wrote the “Dear American Jews” page. It bubbled out of me after a year — my first year — of participating in organized American Jewish spaces, retreats, organizations, places of worship. I wanted non-Soviet American Jews to understand that, though many of us are white and pass as white Americans and are complicit in U.S. whiteness, we have very specific lived experiences, family histories, desires and pains that are not the same as those of white American Jews who have been here several generations. We want American Jews to be careful to not abstract and appropriate that which is sacred to us and is of our lifetimes – our language/accents, the stories we heard growing up, clothes our family members may have worn, the lands we grew up in, etc. This is American imperialism and white supremacy in action, and it’s especially painful when the people doing this benefit, either socially or financially.

Stepha: As Sophia mentioned, some people tokenize our culture. When I experience this, I get the same feeling as when I’m watching a movie and encounter a villain who speaks like my grandfather– a sinking feeling of shame and a rising feeling of rage. It’s only recently that I started investigating the American stereotype of the Eastern European villain (or spy, or sex worker), and I found that its roots go deeper than the twentieth century. American characterizations of Russians during the Cold War draw on older hierarchies within European societies, in which Western Europeans described Slavic people as barbaric and savage. Western Jewish communities internalized these hierarchies, deploying them against Eastern European and Middle Eastern Jews— and they, in turn, against Palestinians— in what Aziza Khazzoom, a Mizrahi Jewish scholar, beautifully describes as a “great chain of orientalism”. As a white person, I don’t experience violence in the way that racialized people do. At the same time, I’ve realized that by resisting American tokenization, I am pushing back on a larger system that represents some groups as unsophisticated in order to dehumanize and exploit racialized communities.

In other cases, American Jewish folks have made assumptions about what it means to be Jewish. When people assume that we all know Jewish prayers and songs and traditions, they ignore our experiences. The Russian Empire and the Soviet Union forcibly assimilated our ancestors, and we live that legacy every day, in ways both difficult and beautiful. My ancestors made choices to ensure my survival and the culture I received is a product of those choices. Putting sour cream on my pelmeni feels like home, and I am learning to find home in Jewish practices as well. I am deeply grateful for my American Jewish friends who acknowledge my experiences alongside theirs, who pray very slowly so that my voice can join theirs.

The zine also explores questions of whiteness and assimilation. How do you feel that your identities inform your relationship(s) to whiteness?

Sophia: Not all post-Soviet Jews are white, of course, but everyone in the kolektiv right now is white. So, we’ve talked a lot about whiteness. It was the first topic I raised. To the extent that we’ve shed Russian accents, in the U.S. and Canada most of us have been read as white most of the time. This is interesting because race and ethnicity worked differently in the contexts we left. We definitely were not full ethnic Russians or Slavs (some of us are half or part) and we definitely were ethnic Jews, via the “nationality” (ethnicity) marker on our passports. So, we moved from a context where we were an ethnic “other” to a context where we were absorbed into the racially dominant group.

Most of our families jumped at the chance to not be ethnically marked and to take advantage of opportunities like purchasing houses, securing access to resourced schooling, and gaining stable, well-paying jobs. Some of this had been kept from them via Soviet antisemitism. But, for some of us with leftist politics and critical white consciousness, this feels absurd and wrong. We feel a responsibility to work against white supremacy, given our ancestral histories, familial experiences, and the ways we benefit/are complicit in our new diasporic context.

It has been strange to be read exclusively as white Americans when we are also post-Soviet Jews with vastly different histories and life experiences from white Americans who have been here for many generations, including white Jews. Of course we have benefited so much from systems of white supremacy and racial capitalism. That must be said first. At the same time, our histories and cultures have often been erased within hegemonic whiteness and even U.S. Ashkenormativity. This erasure and assimilation has been painful and lives in our bodies. It is not abstract because the things we’ve denied have been deeply personal: our language, our familial relationships, in some cases our own names.

For many of us, the kolektiv offered a place to reflect and validate identities and experiences that had been invisiblized, that had been shamed via assimilation, and that we had kept hidden to “pass.” In reclaiming our stories I think we complicate whiteness in a way that is very necessary, revealing its inherent constructedness.

Stepha: Sophia’s response captures a lot of my feelings and thoughts about whiteness. The only thing I really want to add is how much our work together has informed my perspective on recent instances of academic blackface connected to my university, UW-Madison. In both cases, white academics claimed Black and Latinx identities in order to gain access to BIPOC organizing spaces and tenured employment in the academy. These individuals should be taking full responsibility for all of the harm that has come from their choices and, importantly, engaging in reparations with the communities whose identities they’ve profited from. Race is, among other things, a material relationship, and they need to redistribute the resources they’ve stolen.

At the same time, if white organizing and academic spaces work to complicate the category of whiteness, it might help mitigate the temptation to claim a false identity in order to explore one’s embodied trauma. Learning from Resmaa Menakem’s writing on race and somatics, I’ve developed a better understanding that all of us inhabiting white bodies benefit from white body supremacy, and some of us carry different types of intergenerational trauma in our nervous systems. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the academics in question have Russian-Jewish and Sicilian ancestry — these groups have long trajectories of oppression by Christian Europeans and northern Italians, respectively. People can’t tell just by looking at me that my family members survived state violence, but my body doesn’t let me forget. That trauma needs a place to get processed, and it’s on us as white folks to create spaces where we can explore the internal hierarchies that make up whiteness. We need spaces to validate and heal those wounds so that we can mobilize more effectively against racial injustice instead of invading and violating BIPOC spaces.

Anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism seem to be centerpieces for the politik behind this zine. As diasporic people, it seems particularly important that Jews are self-aware and reflective of our relationship to colonization, land, and empire. How would you envision a better Jewish relationship to colonialism and imperialism?

Sophia: We are approaching our work with a decolonial lens, working toward rematriation of the land to native people and reparations for descendants of enslaved African people (as well as a transformation of the violent structures that make oppression possible). We have talked a lot about shifting our relationship to all living beings toward an interdependent, spiritual, non-extractive way of being. For me, this means the abolition of private property and colonial and racial-economic hierarchies of power, and the establishment of systems of interdependence and mutual aid (many communities, groups, collectives have been/are already doing this of course!).

Colonialism and imperialism have hurt Jews in countless ways, and I don’t think we should now be seeking safety and protection in land ownership, occupation, or ethnonationalism. I believe in radical diasporism as envisioned by Melanie Kaye-Kantrowitz and the Bundist notion of “doikayt” (here-ness) – that is: a radical, decolonial and anti-racist engagement with the land and peoples wherever we happen to be living. The best way to be in Jewish relationship to colonialism and imperialism is in solidarity with colonized people.

Stepha: The best Jewish relationship to colonialism and imperialism is one of antagonism. This antagonism can be informed by histories of Jewish struggle against forms of oppression based on embodied difference. Cedric Robinson, a Black Marxist, writes powerfully about how anti-Semitism (and the subjugation of Slavic people, along with many other minoritized populations) helped to differentiate classes of workers, thereby serving as the basis for the emergence of a racially-stratified European capitalism. Jews and Moors were driven out of Spain following the Inquisition, and their wealth was used to fund the genocidal colonialism of the Columbian expeditions. In our collective, most of our ancestors were confined and economically exploited within the Pale of Settlement in Eastern Europe.

These legacies — of conquest, exploitation, expulsion, confinement — make it clear how the regulation of land, mobility, and labor have been at the heart of capitalism, colonialism, imperialism, and militarism. For those of us who have benefited from assimilation and class mobility to the point where we can comfortably reflect on these histories, the task is to access the urgency and motivation of our ancestors in transforming these violent structures so our feelings of comfort or perceived security don’t make us complacent.

Will there be a second zine from Kolektiv Goluboy Vagon? What’s next?

Sophia: We always have more ideas than resources. Time is a big issue. There are a few zine ideas in the works! We are also hoping to onboard new members, who have been waiting many months to join the kolektiv. For now, we are building up our committee to make the kolektiv more sustainable, archiving our materials and building out our website, and figuring out our Winter season.

One of our biggest dreams is to build up a coalition of various immigrant groups that works from the specificity of our various experiences in solidarity toward de-assimilation, reparations and rematriation. Many of us have been dubbed “model minorities” or “model immigrants” and it’s long been time to subvert that label against the system!

What was the most meaningful part of creating this zine?

Sophia: For me, it’s been allowing myself to give voice to parts of myself that I have denied and kept hidden out of fear of “taking up space.” For many months our work happened on Zoom – it was virtual, ephemeral. We were working hard and thoughtfully but there was no physical evidence. It’s been powerful to have a tangible product – a thing to hold in my hands that’s colorful and beautiful and compiled from many people’s words and writing. And, of course, sharing this thing with others beyond our kolektiv. I still struggle with sharing this work with people in my life who directly suffer from anti-Blackness and anti-indigeneity because I am worried about taking up space with white-written narratives, even if our aim is to counter whiteness. But the response to the zine and online zine launch has been incredible. People are saying “Yes! We need more of this!”

Stepha: I loved the first moment of opening the shared folder and reading through everyone’s submissions — it was the first moment I realized just how powerful this project would be. ⋄

If you’d like to order your own copy of the Kolektiv Goluboy Vagon zine, you can purchase a copy here. To learn more about Kolektiv Goluboy Vagon and its members, visit their website here.

Read more about Jewish zines and find the other Hanukkah Jewish zine features by visiting our holiday landing page here.