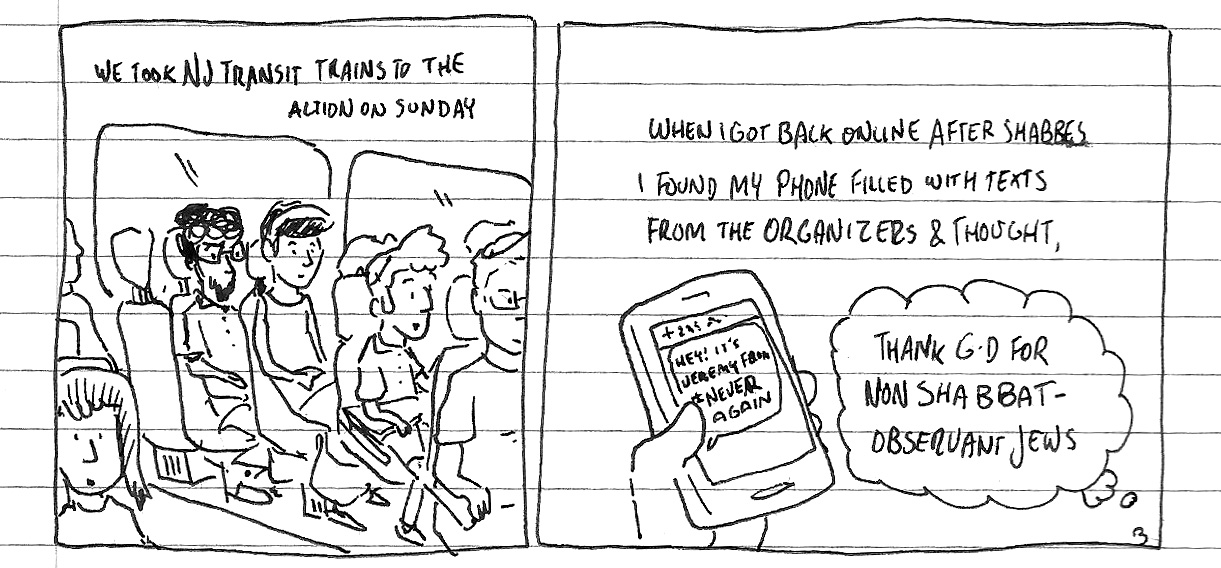

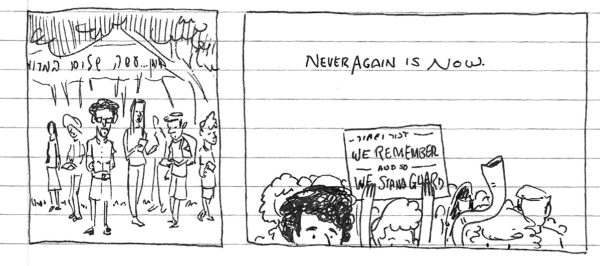

On the train down from Manhattan to Elizabeth, New Jersey, I sat with cardboard box flaps in my lap, materials for poster-making. When we got off at the station I’d leave them on the train by accident along with my sunscreen, but until we reached our stop I lay back in my seat, tired from the early morning and listening to conversations between friends and friends of friends overlap above my head. For some of them, today would be their first protest. Others had been at this for a while. I guess I was somewhere in between. What made this feel different was that I wasn’t heading down to this action alone; I was sitting with a cluster of other Jews on our one day off from Yeshiva, going to an action at the Elizabeth, New Jersey private detention center to shout Never Again.

From June to early August I attended Yeshivat Hadar, a Jewish house of study in New York City, as a student in the summer learning intensive program. Every weekday, my housemates and I rose at dawn to take the subway from Washington Heights to the Upper West Side in time to say morning prayers at shacharit, then learned Talmud and other rabbinic commentaries until dinner or dusk. And in the moments in between, stepping out of the beit midrash and hazily rejoining with the world beyond the study hall, checking my phone, the headlines stacked up and grew darker.

In the heat of summer 2019, American concentration camps across the country swelled with children severed from their parents. Policies and horrors: The Trump Administration refuses to give toothbrushes or vaccines to detained people. Indefinite detention becomes possible as politicians desecrate the Flores settlement. Detained children cannot touch or hug under the auspices of the guards. ICE raids abduct undocumented parents at their workplaces and their kids return from school or daycare to empty houses. Children die in cages under government custody. The blood is on our hands. The cruelty is the point.

Returning from a short break, after sitting on the lawn outside between classes and reading the New York Times’s inside look at the squalid conditions in an American concentration camp in Texas, complete with maps demarcating where children are held in cinder block cells and auxiliary tents for overcrowding, I stare at the wall of prayerbooks and wonder: How can I learn Torah while the world is burning?

Back on the train to Elizabeth, I turn around in my seat and ask the same question to Rabbi Aryeh Bernstein, a friend and mentor riding behind me.

“I don’t know how to justify spending so much time learning, especially if it means I have less time to participate in actions like this,” I said. I was picking at my cuticles, and he put his hand on mine to tell me to stop. I put my hands on my knees instead. “How do you learn Torah while the world is on fire?”

He crouched forward and thought for a while. “When I’m in the beit midrash, I know I’m not there forever. I have to take that time seriously, be focused in what I’m learning. If you’re studying, my advice is this: don’t fuck around.”

____

The Friday before the protest fell on Parshat Shlach, the Torah reading in which the Israelites stand nervously outside of the Promised Land, waiting to hear reports on the unknown. Ten of the twelve scouts return with terrors: There are giants in the land, they say, and we don’t stand a chance. “This is a land that devours its inhabitants. All of the people we saw in it were huge in size…We looked like grasshoppers to ourselves, and so we must have looked to them.” (Numbers, 13:32-33).

But after the amazing rescue from Egypt, the revelation at Sinai, the daily wonder of the manna, and the countless other miracles throughout the desert, how could the Israelites be so scared? We don’t live in a world where we feel so close to G-d so regularly, but they did. If you see divine power every single day, how is it that they had G-d’s promise of safety, of everything working out okay, yet were still terrified?

At that point in their journey, the Israelites were known as warriors, feared by other desert peoples after having defeated so many tribes who attacked them. There weren’t even very many giants in the land of Canaan – so what were they really afraid of?

More than being afraid of giants, more than being afraid of the future, the Israelites were afraid of success. The Lubavitcher Rebbe teaches that they were afraid of their own power. Recognizing what they were capable of meant that they would be obligated to act.

The debate about this is old: which is greater, study or action? A story:

“Rabbi Tarfon and some elders were reclining in the upper chamber in the house of Nitza in Lod when the following question was asked of them: Which is greater, study or action? Rabbi Tarfon replied and said: Action is greater. Rabbi Akiva replied and said: Study is greater. They all replied and said: Study is greater because study leads to action.” (Kiddushin, 40b).

They wrote that a couple thousand years ago. But even today it complicates my heart.

___

Does study lead to action? What kind of study, what kind of action? I’ve spent enough time in academia that I’ve become wary of calling knowledge an action unto itself, without fault or failure. I’ve seen my share of papers with authors whose only interactions with poverty is theoretical despite their accolades in sociology or economics. I know students who have spent years at my university and never ventured a few blocks south of campus, where the high-rises turn to apartments and rental houses, and the only grocery store in the area was recently announced for closure. It is easy to critique from the high castle, hard to bring knowledge into the realm of action.

Maybe what distinguishes Torah from other kinds of knowledge is its intrinsic link to action. Maybe Torah is a world of thought where there is no line between values and our deeds. Academia isn’t Torah, but it’s not wrong to want knowledge to aspire to something better, to believe that good ideas should naturally lead to change. Though I may have been learning in yeshiva this summer, I’ve returned to university this fall and find the same problem. It’s a privilege to get to learn like this, but it has to be oriented towards the world, the problems facing the people we love and the people we are obligated towards.

There’s this tradition to dedicate Torah learning to those in need of healing or those who have passed away. Sometimes source sheets or learning sessions will begin with this kind of intention setting; the Torah we learn commemorates and honors, orients us towards both someone and something. Before you sit down with an open page of Talmud, or the weekly parsha, or any of the texts that weave a vibrant tapestry of wisdom, there’s a blessing to say before the act of learning.

One morning after the Elizabeth, New Jersey protest, when I sat down with my chevruta for the morning seder of Talmud where she and I broke our teeth on Hebrew and Aramaic, before we cracked our dictionaries and opened the brigade of books we needed to dive into the waters of thick, dense Torah, I asked, “Can we dedicate this?”

I didn’t want to forget why we were here.

Study can give us meaning, Torah can root us in our intentions. Stepping onto the subway after yeshiva, late on the Tuesday after the action, I remember the quote from Kohelet, “a time to weep, a time to laugh // a time to mourn, a time to dance.”

I stare out the traincar windows into the darkness of the tunnels. Maybe there can also be a time to learn and then a time to act. Maybe they need each other like the seasons blend into one another. It’s said that Torah is like water. If the world is burning, if I can be a vessel for Torah, maybe I have a chance to help save something from the flames.