Photo credit: Josie Krieger.

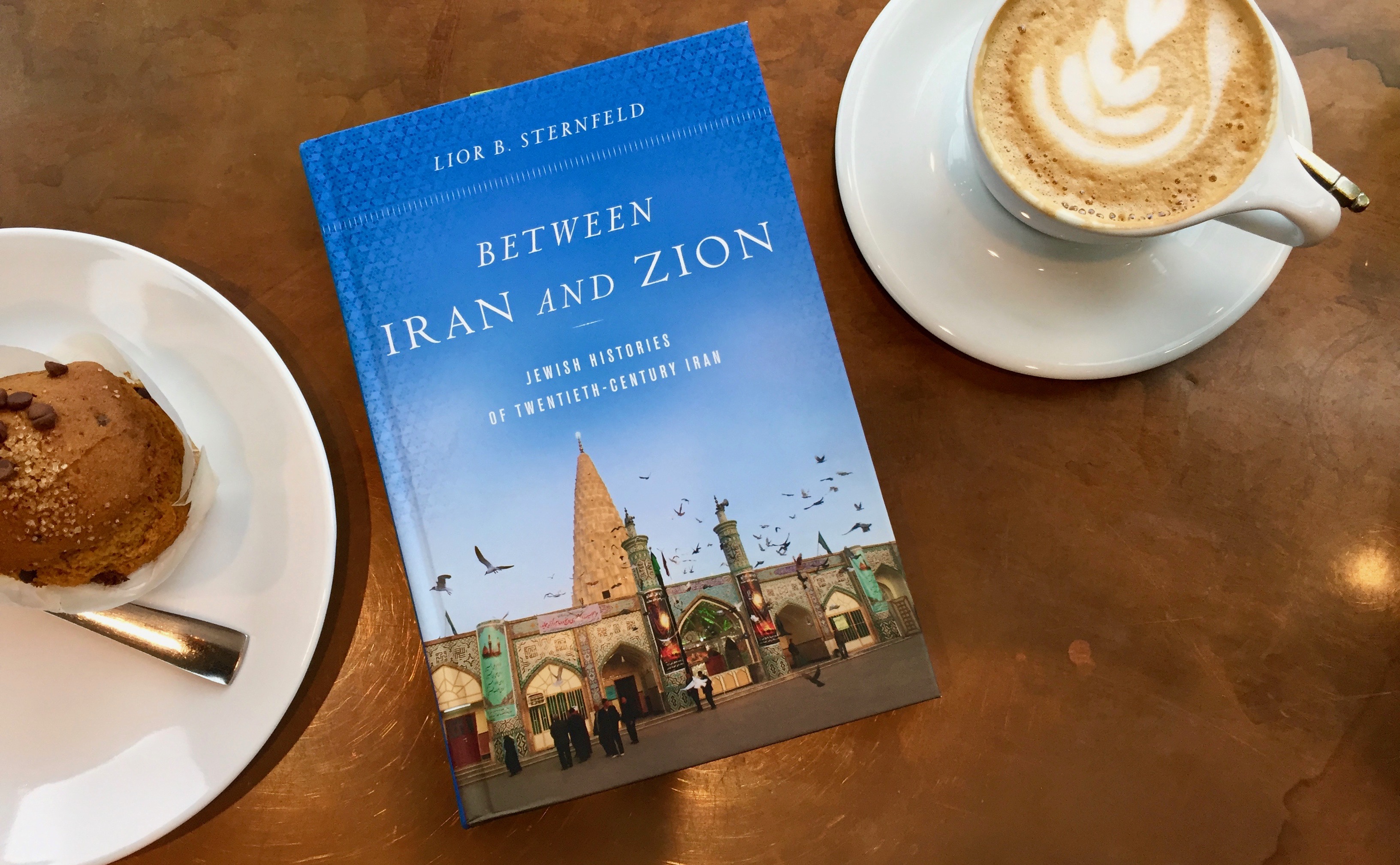

Lior Sternfeld wants you to judge his book, “Between Iran and Zion: Jewish Histories of Twentieth-Century Iran,” by its cover. Depicting the Tomb of the prophet Daniel in Susa, Iran, its movement and color speaks to the relationship between Iranian Jews with other Iranians – and other Jews. The fluid and effervescent image on the cover represents both the “Muslimness and Jewishness in the realm of Iranian culture” and reflects Sternfeld’s challenge to expand past the typical Iranian Jewish narrative, focusing on more than the lachrymose history and post-Holocaust Zionist movement.

Sternfeld offers a commonly overlooked perspective of the Iranian Jewish minority, whose history is traditionally characterized as a homogeneous tragedy, overlooking the impact the Jewish community had on Iran and vice versa. Through oral histories and communications with colleagues in Iran, Sternfeld explores the uniqueness of Iranian Jewish life and the conflicting identities resulting from the community’s relationships to Zionism and Iran throughout the twentieth century.

Sternfeld, assistant professor of history and Jewish studies at Penn State University, is an Israeli citizen, which meant that he was unable to enter Iran himself. Unable to conduct any on-the-ground research, Sternfeld relied heavily upon oral histories from Iranian Jewish communities around the world, all of whom detailed their love for Iran through stories of acceptance and strength.

“They feel part of Iran,” Sternfeld said. “This was part of their struggle for [years].”

———————————–

Jews have inhabited Iran for over 2,700 years, and yet their struggle for identification and affiliation has been omnipresent. Iran became a site for refugees during World War II, as 200,000 to 300,000 refugees arrived between 1942 and 1943, most of whom were Polish. The Iranians were “happy to help the refugees,” and their generosity was genuine, Sternfeld illustrates.

Between 1948 and 1951, the Iranian Jewish population shrunk by over 21,000 individuals, but Iranian Jews who remained developed deeper ties in the Iranian community. However, many Iranians were facing economic hardships; they believed that having a Jewish background would help them access immigrant visas to Israel, a state they hoped would offer peace and stability.

Sternfeld sheds light on the Jewish community’s reasons to leave the country, and in doing so indicates their reasons to stay. Although some Iranian Jews decided to emigrate, others decided to continue to build their lives in Iran. Furthermore, almost 1,000 Iranian Jews wished to return to Tehran from Israel where resources were quickly being used by the mass influx of refugees. However, as many continued to leave Iran, the Iranian Jews who remained enjoyed more opportunities and heightened social status.

Iranians had to choose: should they stay in Iran or leave with thousands of others Jews and build a life in Israel? Sternfeld illustrates the importance of the choice for the Jewish population in Iran at that moment in time.

“Zionism began to symbolize a point on an imaginary axis,” Sternfeld writes, “with one end symbolizing ‘very good ideas for other Jews’ and the other end, ‘a good plan B in case assimilation in Iran amounts to total failure.’”

Many Jewish Iranians chose to remain in the country during the 20th century, and, Sternfeld highlights, they intentionally remain in Iran today. Zionism and Judaism are separated in Iran, unlike in many other nations. Iranian Jews articulate their identities as intentional choices, seeing themselves as both proud Iranians and proud Jews, while not necessarily being Zionists.

“[Iranian Jews] are not there because they don’t have any other option,” Sternfeld said. “They wake up every morning and they choose to be in Iran.”

A majority of Sternfeld’s interviewees in “Between Iran and Zion” reside outside of Iran. The communities, although unique and widespread, all share a communal closeness. When he began his book over ten years ago, Sternfeld found that people were reluctant to share their personal experiences, unwilling to recall the events they saw or contributed to, because the Iran many Jews fought for changed. However, his oral histories ultimately show readers that his subjects are proud Iranians above all else.

As Sternfeld addresses in his book, the Jewish population played an important role in student organizations and other opposition groups during the 1979 revolution, “sympathizing with their compatriots, setting aside their community’s alleged inherent support of the monarchy.” Their assimilation led to their ultimate political activism, changing the history of Iran as they became more involved, protesting in the streets and even opening hospitals.

Sternfeld stresses the importance of the Sapir Hospital in Tehran during the 1979 revolution. With a sign on the front of the building saying “Love thy neighbor as yourself” in Persian and Hebrew, the hospital played an instrumental role in protecting and healing protesters, refusing to turn the protesters over to the Shah’s secret service even though other hospitals complied. The Iranian Jews of the city protected their fellow Iranians, allowing unification under the Iranian identity rather than division through religious identities.

Haggai Ram, associate professor at Ben Gurion University of the Negev and author of “Iranophobia: The Logic of an Israeli Obsession,” sees Sternfeld’s book as powerful and unique.

“Lior’s book is a revisionist history of Jews in Iran,” Ram said. “Not only is it revisionist, it is well researched. It’s not polemical. It’s a provocative book because it deconstructs many narratives about Iranian Jews. It will make a big difference in Jewish history in general, and in Iranian history in particular.”

Sternfeld’s ability to analyze and reexamine the Jewish minority’s impact in Iran moves readers to understand the subject further. His research and thoughtful examinations of oral histories are, like the cover of his book, dynamic and thought-provoking, making readers want to pick it up off the shelf and learn more.

Josie Krieger is a student at Penn State University.