A few weeks ago at JFK airport, I huddled with fellow Brown University students and members of IfNotNow near the El Al check-in line. The airport was crowded that night. It was filled with anxious travelers of all sorts, including dozens of young Jewish adults searching for their Birthright groups. As they wandered the airport, many of these travelers found us. We held a sign (“Going on Birthright?”) and carried IfNotNow’s logo, a flame that represents our movement’s mission to end our community’s support for the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. Before pointing students in the direction of their trip leaders, we handed out informational guides and materials and encouraged them to ask questions about the occupation while on their trips.

I went on Birthright in the winter of 2017. I called my sister right after I signed up, and I remember being surprised when she criticized my decision to go. She asked how I, a progressive American Jew, could support everything Birthright stood for by accepting a spot on the all-expenses-paid trip to Israel. If I went on the trip, wasn’t I saying I was okay with Israeli settlements in the occupied territories? Wasn’t I saying I endorsed some of the biggest funders of Trump’s presidential campaign because I was accepting their “gift” of this trip?

At the time, this idea didn’t make a lot of sense to me. All I really knew about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was what I’d learned from its Wikipedia page. But I did know that I wanted to learn more about it, and figured the best way to do so was to take a free trip that would bring me to the site of the conflict. So I ignored my sister. I told her I was taking the trip for educational purposes. It wasn’t until I’d arrived in Israel that I realized I wasn’t going to get the sort of education I was hoping for at all.

Birthright vaguely defines itself as an “educational trip” on its website, promising “a culture of open discussion and dialogue about all issues: identity, geopolitics, religion, and Jewish life.” That means a lot of students sign up for the trip, like me, under the impression that they’ll learn about all sides of the story. They’ll have a chance to ask questions about the contested borders of the state; international impressions of those borders; the lived experiences of Israelis and Palestinians in contested territories; and the complex truths behind why this conflict is so hard to resolve.

But on my trip, we had no such discussions. Questions about the occupation were pushed aside with responses like “it’s complicated.” At the Golan Heights, we were fed reductive impressions of Palestinians as dangerous, impulsive terrorists. My phone buzzed with a message from Verizon, alerting me that I’d crossed the border into Syria and would be charged for entering a new country on my international plan. Our guide insisted we were still in Israel. Later, we drove past the separation wall in silence, most participants napping on each other’s shoulders. The tour guide faced straight ahead, his microphone turned off. Over the course of my trip, I learned more about Birthright itself than the complex reality of the conflict: it is an organization that does not seek to tell the truth, but rather to convince its participants of Israel’s uncompromised benevolence. I realized I should’ve taken my sister’s concerns more seriously. Instead of receiving a gift, had I accepted a bribe?

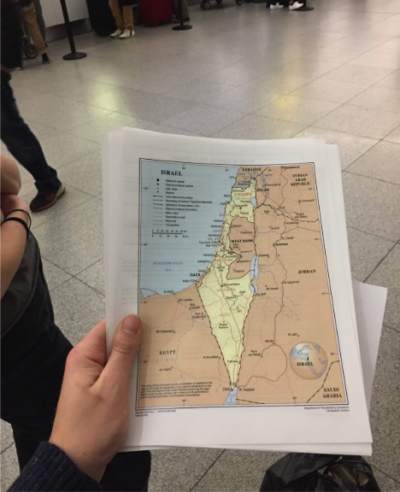

At the airport last week, I hoped the resources I handed out to my fellow students could change their trips. I hoped theirs could be genuinely educational, unlike mine. We handed out a map that showed the West Bank and Gaza Strip, so that participants could compare it to the one Birthright would give them (which shows the occupied territories as uncontested parts of Israel) and ask about the differences. We gave them questions to ask about the lived experiences of Palestinians and the restrictions placed on their civil rights, access to resources, and movement. We gave them facts and statistics about the occupied territories to consider alongside the information they would receive from their guide.

And, perhaps most importantly, we made them wonder why Birthright wouldn’t provide them with this same information. Hopefully, many questions will begin to rise to the surface. Who dictates what narratives dominate this trip? Who funds it? What are they invested in, and do they represent our Jewish values? Do they help us pursue the justice, knowledge, and open dialogue that our community taught us to treasure?

Young Jews should think long and hard before signing up for a Birthright trip. But many, like me, will choose to go, hoping the experience will educate them. They expect to come back informed and ready to engage in difficult discussions about Israel-Palestine. My friends who have gone on Extend trips to visit the occupied territories and speak to Palestinians certainly feel that way. But those who attend Birthright and accept the simplistic, incomplete narrative it pushes will not. They will learn only what its funders want them to, because they, like many other mainstream Jewish institutions, are invested in the ongoing occupation. These funders and institutions want our generation of young Jews to continue donating money to them and offering unconditional support for Israel from abroad.

Groups like IfNotNow are committed to asking the essential questions that will round out the education we receive, allowing us to learn what these funders don’t want us to know. We refuse to accept the sugarcoated story we are fed on Birthright. Instead, we want to learn about the complex reality of the occupation. We demand that Birthright show us the truth.

Lucy Berman is a member of the IfNotNow Providence and Boston hives. She is currently a student of religious studies at Brown University and plans to graduate in May.

Featured image credit: Pixabay.com/olafpictures.