This column was originally published in The Cornell Daily Sun on October 27, 2017. Read more at cornellsun.com.

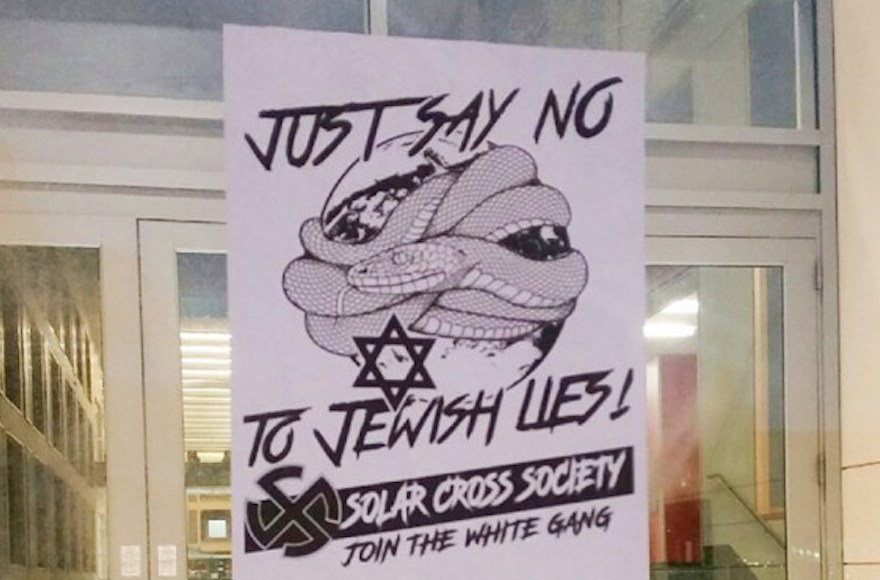

Last week my Judaism became suddenly quite visible. When anti-Semitism was plastered across campus, Jewish went from being a private piece of self to the subject of public discussion, in classrooms, on social media and with peers. Yet even in a moment when Jewish identity was directly vandalized, the conversations I had remind me that my lifelong experience with American Jewry has been a constant tension. On one side is the rich and complex sense of Jewish self that my parents and community have offered, while on the other lie the two-dimensional assumptions of everyone else.

Recently, Jewish has been something I have searched for in places where it once thrived. I have spent hours in the quiet corners of cities where I was told the Jews used to live. Lisbon, Rome, Paris, Manhattan. In the churches and gift shops I imagined synagogues and bakeries, teeming with community and commonality. On the Lower East Side, in front of a Starbucks that may have been a deli or a Yeshiva, I listened for the echo of identity still bouncing off the sidewalk. Last spring, my father found an old book written in Hebrew and sent me up 40 blocks to West Side Judaica to talk to a woman who might know what it was, and what kind of Jewish we could find between the pages. Over the summer he dragged us to the basement of the Library of Congress where they stashed Gershwin’s piano and Ira’s pen. We went there searching for Jewish too.

Fifteen years earlier, my Jewish memory began privately, and in borrowed space. It was the basement of a Unitarian church that leant us the room on Saturdays and holidays. From the beginning, Jewish experiences had to be created with deliberate care. My notion of what faith meant was a direct function of the choices my congregation made, choices I feel tremendously proud of. As a result, my first experience with being Jewish was intimate, something for family and the people who taught me how to pray. It was an identity borne and experienced around kitchen tables and in private religious spaces. It was quietly, obviously my own.

As I got older, though, I began to encounter a kind of Jewish that was no longer private. It was a public identity, and one that carried meaning that was not my own. I watched that meaning unfold in front of me, shaded and shaped by the 99.03 percent of my hometown that didn’t hold it. Whether it was teachers asking just me how I felt about Israel, or a classmate gently confiding that he had forgiven us for killing Jesus, Jewish was something on which everyone held an opinion. Wracked with 16-year-old anxiety, there was no part of me that wanted a signifier of difference, and especially not one that would make me a certain way, whatever that way may have been. So I began to keep Jewish tucked in my back pocket, glad at times that you could not see it on my face.

But try as I might to avoid these conversations, the world is full of non-Jews who are quite sure they know what Jewish is. So, I am often handed a history beginning in 1946. The Jewish experience, some say, is meant to be understood only in terms of its relation to the Holocaust, or perhaps to the Zionist project. At its best, we are given a long view of history, but only allowed to pick out the most painful bits. The Jewish I have been given by my parents is Benjamin in Germany and Gershwin in New York; the rest of the world offered history lessons about pogroms and inquisitions. It is the flat, two-dimensional identity of the victim, and bears no resemblance to the personal, joyous Jewish that I know to be ours.

The most common, and frightening suggestion has been that there is no unique identity at all. Time and again, I have been asked to justify why being Jewish should mean anything more than faith. I am a white American, so is my father, and so is his. We have been safe and stable for nearly 75 years, and we have a state that represents us. We are highly integrated, socio-politically empowered and some of us eat ham. Jews are white, I am told, and nothing else. No culture, no history, no people. Just a shorter book.

Thus my experience of diaspora Jewry in America has been a bombardment of unhelpful suggestion, resulting in the growing sense that perhaps I should abandon that identity in place of one that would meet less resistance. This is what I find truly frightening. Despite the constant labor of family and community to instill something valuable, my Judaism was sometimes eroded, not through clear acts of violence and hate, but rather by the insistence of the others around me that they should have some say in what it means. I became less vocal about my faith, and less attached to my community. This is a dynamic that threatens to make Jews less safe and Jewish more invisible. As a people, in that small way, we become an easier target.

Finding Jewish has been a lifelong project, structured and supported by the Jews I know and love. However, despite the best intentions of a mostly accepting community, Cornell and places like it have a way of making that project much more difficult. It isn’t enough to simply say that we do not tolerate Nazis, and as Jews, this is not the only thing that we should ask. Instead, Cornell’s community needs to begin listening to Jews when they describe what their faith means to them. This community must be willing to internalize a more nuanced and complex understanding of Jewish identity. Anything less will only further obscure a people that centuries of violence have already sought to bury, and make it harder for us to begin looking ourselves in the first place.

Rubin Danberg Biggs is a senior in the College of Arts and Sciences. He can be reached at red243@cornell.edu.