When my great-grandfather left England around the turn of the century, in part due to anti-Semitism, his name was Harris Moses. By the time he set foot on U.S. soil, it had changed to the much more goyishe Julius Harris.

Of course, he was not the only immigrant Jew to change his name to better his chances of entering the country. Cohens became Coles, Herzls became Harts, and Salomons became Sloans. At that time, increasingly restrictive immigration laws were being passed to prevent successive mass waves of Jews fleeing anti-Semitism and poor conditions. These Jews were seen as poor, dirty, and uncultured.

The situation only grew worse with the advent of European fascism and the rise of Hitler. Throughout the 1930s, Jewish refugees fled Nazi Germany for Palestine, France, Latin America, and the United States. By June 1939, 300,000 applied for just 27,000 US visas.

The much-publicized case of the St. Louis, a refugee ship that was turned away from American shores, is now being recounted in a haunting Twitter memorial. “My name is Max Wolff. The US turned me away at the border in 1939. I was murdered in Auschwitz,” one tweet reads.

By the 1930s, the perceptions of Jewish immigrants had changed somewhat. In addition to posing an economic and cultural threat, these Jews now represented a political threat as well. They were viewed as a fifth column who might serve as spies for Germany or as Zionist influencers.

Much of the rhetoric that surrounded Jewish immigrants and refugees in the early twentieth century is being echoed today by the White House in their discussions of undocumented immigration and refugees from Muslim countries.

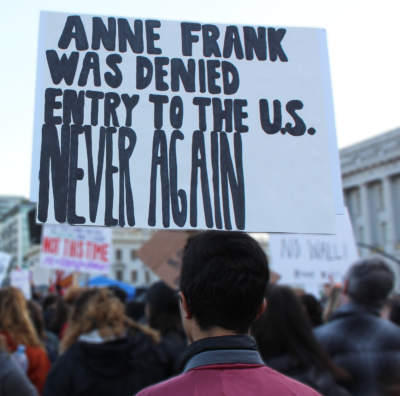

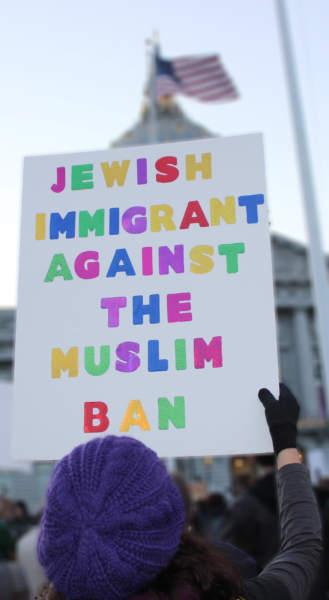

In response, the fierce backlash against President Trump’s travel ban – which suspends immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries – has taken on a uniquely Jewish character. Throughout the past two years, Trump’s opposition has compared him to the Nazis or other fascists, and the refrain that Islamophobia mirrors anti-Semitism is quite common. Never before has the language of American protest been quite so Jewish in nature.

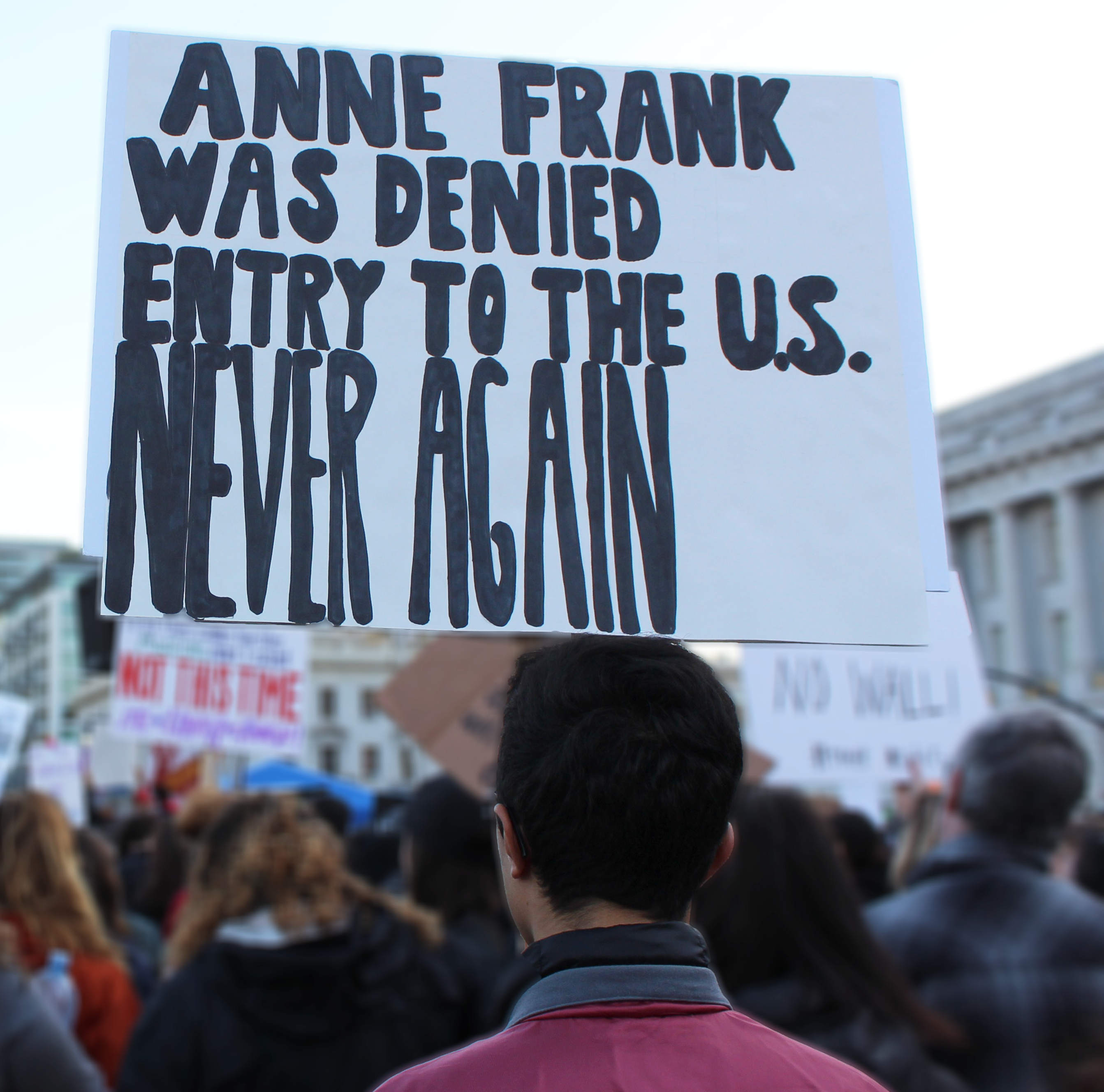

References to the turning away of Holocaust refugees have become more common in recent weeks. (This is, after all, why the St. Louis twitter page is trending in the first place.) The historical connections between targeted bans on Muslim immigration and targeted bans on Jewish immigration, particularly when the respective populations are in danger at home, are apparent to everyone who knows history. Stories of separated families and individuals forced to return to war zones have a similar resonance. And it certainly doesn’t help that Trump signed the executive order on International Holocaust Remembrance day – even as his administration engaged in what historian Deborah Lipstadt has termed “softcore Holocaust denial.”

Jews especially have rallied around Jewish symbols and organized against the ban, galvanized both by eerie parallels with the Jewish immigrant experience and the ban’s impact on Jews. (According to Jewish immigration and refugee support group HIAS, which opposes the ban, several Jewish families from the Muslim-majority countries have been affected.)

One of the defining pictures of the airport protests against Trump was of Jewish protesters taken at O’Hare by the Chicago Tribune’s Nuccio DiNuzzo. It displays a Jewish boy and Muslim girl smiling at one another while holding protest signs, sitting atop the shoulders of their respective fathers, who appear to be deep in conversation. Jewish Senator Chuck Schumer broke into tears at a press conference.

Major Jewish organizations across the board have come out in opposition to Trump’s executive order. Groups such as IfNotNow and Bend the Arc have joined in organizing protests and rallies against the ban.

Both deploy the aforementioned symbolism, with IfNotNow writing in a statement, “In the 1930s, when Jews were desperate for escape from the Nazis, this country joined nations across the globe in closing our borders. This decision resulted in the deaths of untold thousands of Jews, leading us to say ‘Never Again.’ Now is the time to make good on that promise. Never again. Not in this country nor in any other.” Bend the Arc, for its part, has been pursuing a compelling campaign called “We’ve Seen This Before,” which won The Nation’s Most Valuable Activist Campaign award in 2016.

Jews are stepping up, and protests are tinged with Jewish symbolism and history because we have seen this before. And if never again is to truly mean anything, then we must act now. What we’re seeing today – religious and ethnic scapegoating, blatant disregard for the rule of law and balance of power, and a shocking political disengagement from the majority of the populace – is our past and should be no one’s future.

It’s up to us – as Jews and as Americans, or simply as conscientious people – to stand up for what is right. When I participated in the protest at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport, I bore a sign that said simply: “My great-grandfather had to change his name from Moses to Harris at Ellis Island. No one should have to do that in 2017.” As Jews, we know no one’s name or religion should be an obstacle to coming to this country, not in 1917, not in 1939, and certainly not today.

Marc Daalder is a junior at Amherst College majoring in History. He is a Scribe contributor for the Jewish Daily Forward and has also been published in the Financial Times, the Chicago Reader, In These Times, and the student publication AC Voice.