In the Talmud it says, “Whomever saves a life, it is as if they have saved the entire world.” Yet many observant queer Jews are struggling in the closet and suffer high rates of suicide.

According to Hannah Bar-Yosef, a member of the Israeli Interministerial Committee for Suicide (operated under the auspices of the Health Ministry), last year, 20 percent of Israeli gay and lesbian youth surveyed had attempted suicide.

Acceptance of Israel’s LGBTQ community is far from unanimous. Though LGBTQ life in secular Tel Aviv is energized and welcoming, Orthodox queer Jews face higher rates of depression, often leaving religious communities because of discrimination.

Last month, the DCJCC held “Refusing to Choose: LGBTQ and Orthodox in Israel,” an open forum discussion on the ways in which Modern Orthodox communities are creating room for intersectional Orthodox LGBTQ identities, both in Israel and the diaspora.

The event reflected on how religious Israelis in particular are coming together to “refuse to choose” between their Jewish and LGBTQ identities, despite their marginalization in synagogues and among friends and family.

At the forum, two queer Orthodox Jews on the frontline of LGBTQ activism in Israel addressed this vital issue: Zehorit Sorek, the first lesbian woman to run for Knesset and the founder of Bat Kol (an LBT organization for Orthodox women in Israel) and Daniel Jonas, the head of Havruta (an organization for Orthodox gay men). Both shared their personal journeys and spoke about their efforts to create a supportive religious framework for others.

Rabbi Haim Ovadia of the Magen David Sephardic Congregation in Rockville, Maryland, spoke about his work with gay Jews in the D.C. area and his attempts to make his community inclusive, particularly as a Sephardic synagogue.

“… Several leading Sephardic rabbis in Israel spoke very harshly against LGBT, repeating the Ultra-Orthodox mantra,” he said. “[But] to have an authentic Sephardic response, we must adopt the opinion of Maimonides, who said that one must abide by scientific truth. The Orthodox leadership should make a collective effort to apologize to the LGBT community for mistreatment and harassment, to amend errors and build bridges, and to find ways to allow Jews to embrace their identity and to welcome them.”

Rabbi Ovadia tries to advocate “ …being considerate of different opinions, while emphasizing the humane and sensitive side of halacha,” he said.

“Refusing to Choose” and its speakers exemplify a new focus on Orthodox LGBTQ inclusion in Jewish communities both in Israel and abroad, a shift students are witnessing on campus.

College communities have made notable efforts to accommodate LGBTQ students. For example, Hillel International partnered with Keshet, a Jewish LGBTQ organization, in 2014, with Keshet providing an online Guide to More LGBTQ Inclusive Hillels.

Hillels also increasingly host LGBTQ Jewish student groups, from J-Bagel at the University of Pennsylvania to Gayava at Columbia University. These groups give observant queer students a place to discuss and embrace both of their identities.

A broadcast journalism major, who asked to remain anonymous, found comfort in Hamsa, her Jewish LGBTQ group at the University of Maryland. Once she came out, her relationship with Orthodoxy only deepened, she said. Opening up about her queer identity encouraged her to let both her Jewish flag and rainbow flag fly high.

“I never used to practice niddah (a ritual observed by Jewish women during menstruation),” she said. “But once I came out as gay, I became comfortable enough to enter the mikveh and truly know that I’m b’tzelem Elohim (created in the image of G-d).”

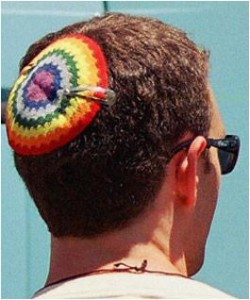

Ari Pelecanos, a business major at University of Maryland at Baltimore County, also found new meaning in Jewish ritual as a queer Jew on campus. “When I wear my yarmulke, it’s more than a symbol of faith,” he said. “It became a symbol of resistance and a political symbol. My yarmulke is rainbow and queer. My yarmulke is resistance…”

For Pelecanos, Hillel has been a support system. “When I go to Hillel for Shabbos, it makes me feel good to know that I am welcomed as a queer Jew,” he said. “It means a lot to me to have cultural continuity.”

Over time, campuses are coming to model spaces where observant Jews can feel both kosher and queer, and – with the help of speakers like Zehorit Sorek, Daniel Jonas, and Rabbi Ovadia – more Modern Orthodox Jews may find support for their decision to “refuse to choose.”

Michele Amira Pinczuk is a student at the University of Maryland.