Everyone is awkward when they start college. Eventually, most students find a group they feel comfortable with, build a community, and the awkwardness goes away. For students with special needs, however, that awkwardness can become a social stigma with aftereffects that can last a lifetime.

People with special needs often report feeling invisible to others, even—if not especially—those who will ordinarily go out of their way to be inclusive.

To change this unacceptable status quo, two organizations have stepped forward to serve as models for the inclusion of Jewish young adults with special needs: the JCC of Manhattan with its Adaptations program and Hillel International with its American Sign Language Birthright trip, among others.

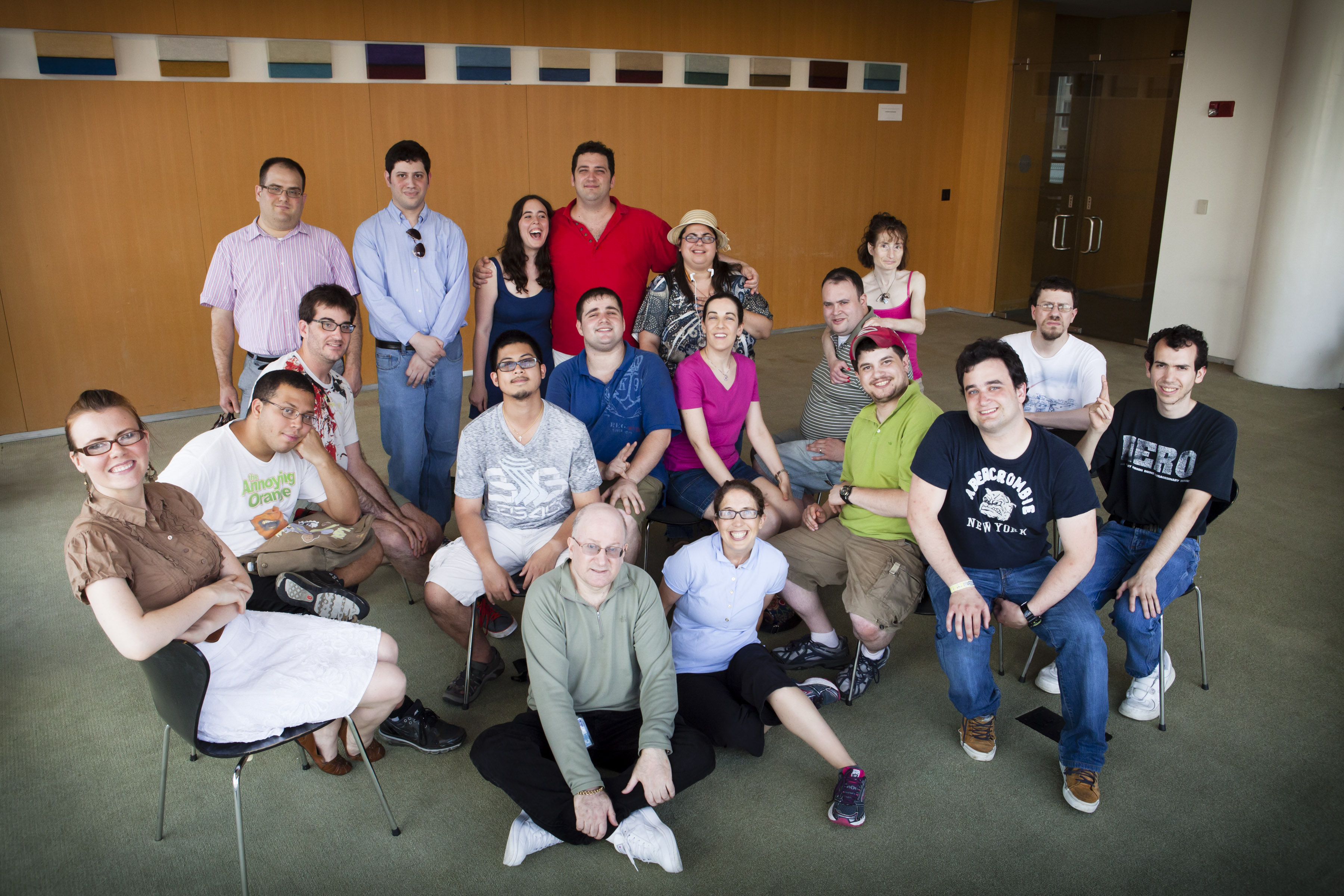

Adaptations builds and supports a community of independent young adults with disabilities by bringing together a wide-range of people, including those with autism, Asperger’s, O.C.D., anxiety, and depression, all of whom are at higher risks of loneliness and isolation.

According to Allison Kleinman, director of the JCC’s center for special needs, the program was born from the realization that, “The whole social world is really challenging for everyone, [but] it is more difficult for this population because of their special needs.”

Without a sense of community, she says, people can find themselves socially isolated and alone, especially after college. This can lead to depression, which she defines as “the feeling that you can’t be your best self.” When someone feels this way, it’s difficult for them to learn hirable skills, and prolonged joblessness can make the vicious cycle of isolation and depression even worse. Adaptations works to ease this stigma by focusing its efforts toward helping young adults work with each other and with non-disabled people through programming such as physical exercise, arts, swimming, sports, and other activities that the developmentally disabled can participate in with the developmentally typical to make them feel normal and included.

“The good thing about Adaptations is that because you’re with other people who have a similar or, in my case, even worse level of dysfunction, you don’t have to feel ostracized, or ridiculed, or judged negatively for it,” said a participating student at a New York school who requested anonymity. “One of the reasons I like going [is because it makes me] judge myself less harshly.”

For Kleinman, the goal is always “to teach people to accept the strengths of people with social stigmas and challenges. In college, we’re all facing it, we all are acting cool but trying to pass. This population is no different. They have so many talents, it’s sad they face stigma.”

Positive experiences like these are what makes building an inclusive college environment so valuable, and part of what makes feeling excluded so devastating. According to the student, maybe the most valuable aspect of Adaptations is the sense of camaraderie it gives him with other participants and the opportunities it provides to process his experiences with peers. “It makes me feel less abnormal, less bizarre,” he said.

This sense of bringing people together also animates Hillel’s policies towards special needs students. Besides having a strict policy in place for making their centers accessible, they have organized Taglit Birthright trips for students with disabilities ranging from autism and Asperger’s to visual impairments and an American Sign Language trip for the deaf.

The ASL trip was spearheaded by Paula Tucker, director of Hillel at Gallaudet, a university for the deaf in Washington, D.C. and Andrea Hoffman, former director of Israel programs at Hillel International, in 2003. The first trip joined 30 Jewish students, mostly from the Rochester Institute of Technology and Gallaudet, with two interpreters. The experiment was so successful that Hillel made a commitment to keep funding the program every year; twelve years later, it still going strong. Besides deaf students, the trip always also includes hearing students fluent in or interested in learning ASL; students with no connection to the deaf community but who, for whatever reason, just want to go on this trip; and two American guides, usually Dennis Kirschbaum, former vice president for campus services at Hillel International, and Rebecca Dubowe, a deaf rabbi. The Israeli guides never speak ASL and often have no experience working with deaf people. Yet, according to Kirschbaum, “the thing that is striking about the experience is that it is the same experience hearing students have.”

This group’s mifgash, or meeting with deaf Israeli soldiers, usually stands out as a highlight—a cacophony of Hebrew, English, ASL, and ISL that, not in spite of, but largely because of the language confusion, is a treasured experience for all involved. And quite empowering.

“I was surprised when I found out deaf Israelis are allowed to serve in the military,” said Sara Collins, a graduate of Gallaudet who did the trip in 2008, adding, “In some ways, Israelis are ahead of Americans when it comes to embracing deaf people as a part of society.”

According to Kirschbaum, though the differences between the countries doesn’t become obvious on a 10-day trip, Israel actually lags behind the US in several key areas of inclusiveness, including not having a full equivalent of the Americans with Disabilities Act. On the trip, however, this really only manifests itself during the visit to Yad Vashem, Israel’s national Holocaust museum. “Usually, [the museum] automatically gives each group a guide with a headset, and you don’t know who you’re getting until you get there. Normally, the guide likes to walk around while they talk, but that won’t work on our trip. So we have to get stools for the interpreter to stand on while the guide stands still, and they aren’t used to that,” he said.

As the father of two deaf children, Kirschbaum knows first-hand the ostracism deaf people can face in the Jewish community and elsewhere. “It was challenging for them growing up,” he said of his children. “My [D.C. area] shul was great about it, they hired interpreters for [services] and for Sunday school, but talking to other parents, it hasn’t been so encouraging. … My friend who’s deaf wanted to join a synagogue and he asked if they could accommodate an interpreter, and they said join first and then we’ll see.”

From her experience growing up in the D.C. area, Collins has found accommodation to be largely a function of the individual community. She says although her synagogue in Silver Spring, Md. supported her, “synagogues in Virginia that open [their] doors to deaf people, unfortunately, are few and far apart.”

In this regard, her experience matches those of the anonymous student in New York. “I don’t face any more ostracism in the Jewish community than in the regular community,” he said, while acknowledging, “I don’t think people wake up in the morning and wring their hands like Mr. Burns thinking how they can make life difficult for people with disabilities.”

Collins agrees that the problem isn’t ill intent, though she has found the Jewish community more inclusive than the wider community. “It’s not that people don’t want to become inclusive, it’s just that there are more practical challenges to consider. In the D.C. metropolitan area, there aren’t that many interpreters who can interpret synagogue services and other events,” she said. “Many people I’ve met over the years within the Jewish community who are very interested and want to learn. However, they don’t know where to start.”

Yet, as these students’ examples show, when institutions do go out of their way to be inclusive, the positive impression it leaves can last for generations. Inspired by her Birthright trip, Collins and other young deaf Jews looking to start families to form a havurah, or intentional group, for providing their children with Jewish education.

These students’ experiences demonstrate how programs such as Adaptations and the ASL Birthright trip can have an enormous impact in making students with special needs feel welcomed and accepted in the Jewish community, which in turn can give them a sense of self-confidence in everything else they do.

With so much at stake, Kleinman believes it’s integral for Jewish organizations to work together and learn from each other’s strengths in addressing these issues. “The welcoming spirit is there, it just needs to be extended to those with special needs,” she said. “We can learn from Chabad’s individual touch, their personal touch and spirit of inclusion.”

Though not all Chabad Houses are currently accessible, the organization has just received a $1 million grant from the Ruderman Family Foundation to be put towards developing “comprehensive programming and initiatives for the inclusion of people with disabilities across the lifespan, including on college campuses,” according to Chabad spokesman Rabbi Chaim Landa.

Still, all acknowledge that there is only so much institutions alone can accomplish. What people with disabilities want most, the anonymous student said, is for people to treat them with more respect. In his words, “When people see me, they keep a lot of distance from me, friendliness and politeness go out the window. If everyone would show basic friendliness or respect to everyone they meet even if they don’t look like they came off the cover of GQ or Maxim, there wouldn’t be so much stigma to being different. If people were to show basic kindness and respect and that kind of thing, that would make things a lot better for people who are often looked down upon.”

Derek M. Kwait graduated from the University of Pittsburgh and is editor in chief of New Voices.