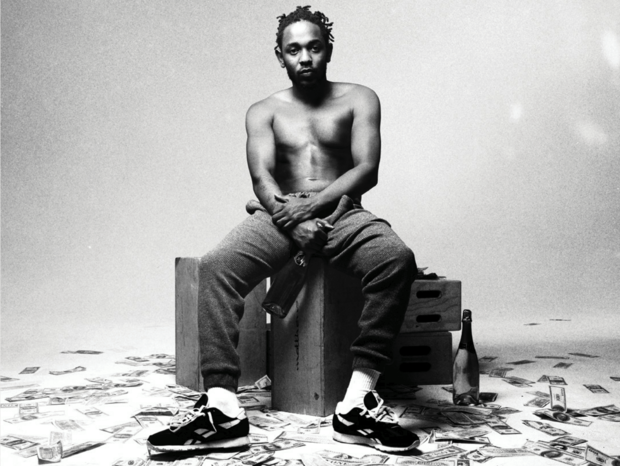

I’ve wanted to write about Kendrick Lamar for a while. Mostly because listening to Kendrick seems to be what I turn to when I’m supposed to be writing, so integrating the two activities felt ideal. But what angle could possibly be found to write about hip-hop for a Jewish student website?

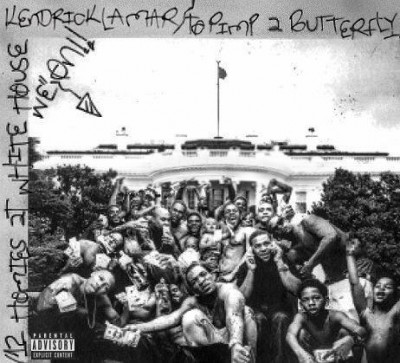

Well, I’m not sure. But after waking up at 6 a.m. to listen to Kendrick’s new album, To Pimp A Butterfly, I have to say something. This is not a review; I’m not the guy for that. All I can do is attempt to articulate my sense that Kendrick is very, very important. To the extent that American Jews, specifically as Jews and not just as people-in-general, must be carefully attuned to social, political, and cultural events, Kendrick Lamar is someone we have to pay attention to.

For the purposes of this article, I’m thinking especially about Judaism (qua religion), in the context of a broader question about divine revelation and how we engage with ostensibly “non-Jewish” sources in our theological inquiry. This shouldn’t be taken as a denial of the Jewishness of non-religious Jews; it simply reflects my particular question at this particular moment.

For most of the second half of the 20th century, many Christian thinkers have recognized the imperative of doing theology in dialogue with the suppressed voices of the marginalized. As a community that overwhelmingly identifies as white, American Jewry needs to pay special attention to black artists and writers as witnesses to the American experience (especially Jews of color). James H. Cone, who is very possibly the most important theologian alive today, describes black artists as “prophetic advocates who can tell brutal and beautiful stories of how oppressed black people survived with a measure of dignity when they were not meant to.” For Cone, the Bible can’t be rightly understood unless it is read in light of the contemporary experience of black people. Just as Cone understands the black freedom struggle in light of Biblical revelation, he argues that Biblical revelation must be understood in light of the black freedom struggle’s witness to God’s liberating reign. “Christ is black,” says Cone, “because he was Jewish.” To proclaim this subversive truth, theology must become an agitator in the struggle for freedom: “Whether whites want to hear it or not, Christ is black, baby, with all the features that are so detestable to white society.” Cone challenges us to approach the Bible as a response to concrete social and political conditions, divinely revealed not in the sense that the words themselves are inerrant, but rather to the extent that it represents the encounter between an oppressed people and the liberating God of Israel.

While Cone’s Christocentric focus obviously cannot be directly appropriated in a Jewish theological context, this method of reading the Bible in light of the contemporary experiences of black people demands our attention. The question is not primarily ethical or political but theological: Who does the God of Israel reveal God-self to be? Cone suggests that the God of Israel cannot be understood apart from the liberating event of the Exodus. Even the law, which rightly assumes a place of centrality in Jewish tradition, cannot be separated from the liberation that precedes it. God is not impressed by power, nor does God side with the stronger; quite the contrary, God chooses the weaker out of, paradoxical is it may seem, God’s universal love. Like a parent adjudicating a dispute between children, God has, as Catholic teaching has held, a preferential option for the poor, deciding for the weaker precisely in order to enact God’s gratuitous love for all.

If this is the case, then not a single word of divine revelation can be understood unless it is understood in light of God’s liberating intent. Insofar as revelation is an ongoing event, which never makes the fullness of God’s being accessible but continually confounds our stable, stale God-concepts, we can then ask where God’s revelation might be experienced today. If Cone is correct, the answer ought to be clear: God is revealed when God’s people struggle for freedom from Pharaoh, for redemption from Assyria, for protection from pogroms. It does not matter what religion those children of God proclaim themselves to be; if we as Jews are to properly talk about our God, we can only do so in view of the prophetic witness of God’s suffering, marginalized, rejected children, the ones Jon Sobrino calls the “crucified peoples.” To paraphrase Pascal, the God of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Hagar, Jesus, Kendrick, Tupac, Sojourner Truth, Nina Simone, and Billie Holiday is not the god of philosophers, kings, tyrants, presidents, prime ministers, and brutal police.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that Kendrick, or anyone, supplants the traditional sources of Jewish religion, but the two must be read in light of each other. Reading Kendrick next to Job tells us something about both figures. In other words, just as Kendrick is like Job, so too is Job like Kendrick. Insofar as that’s the case, Cone’s Biblical interpretation challenges us Jews to face a painful truth: We cannot simply presume that we are the main characters in a given Biblical story. Consider Psalm 137: Are we still the agonized exiles, weeping on the banks of the rivers of Babylon? Or have we ourselves become Nebuchadnezzar? If the text is revelatory, what is it revealing to us, and how do we respond? Re-reading revelation in light of Cone’s critique calls us to a new way of thinking about God, religion, the world, and ultimately also our selves.

Of course, as with the Bible, we cannot approach any artist uncritically or romanticize them to the point of abstract dehumanization. And I recognize that my reflections here are more suggestive than anything else, which is why I consider them above all an “appreciation.” But as To Pimp A Butterfly proves once again, Kendrick has some stuff to say. My point is simply that American Jews, as Jews, should start listening.

Evan Goldstein is a student at Boston College.