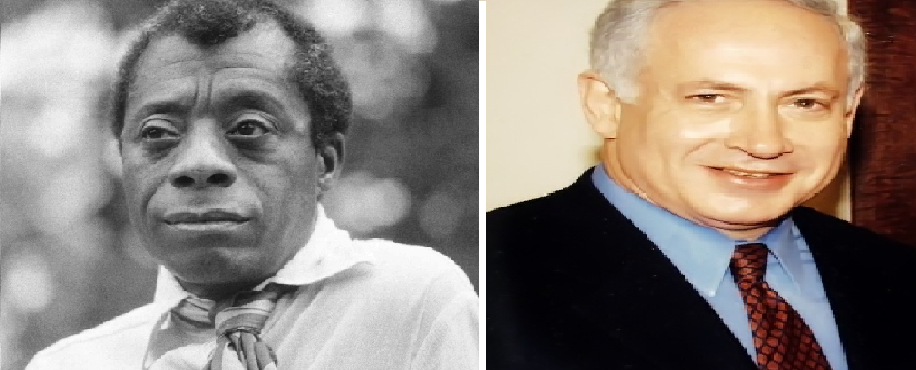

I’ve got this list. On it, I jot down the names of authors I mean to read when I have the time, and at the top of this list is James Baldwin. Knowing little about him, I somewhat absent-mindedly opened a 1967 essay Baldwin wrote in the New York Times Magazine. I was speechless:

It is true that many Jews use, shamelessly, the slaughter of the 6,000,000 by the Third Reich as proof that they cannot be bigots…it is galling to be told by a Jew whom you know to be exploiting you that he cannot possibly be doing what you know he is doing because he is a Jew…one does not wish, in short, to be told by an American Jew that his suffering is as great as the American Negro’s suffering. It isn’t, and one knows that it isn’t from the very tone in which he assures you that it is.

There is so much to be said, and at the same time, no words that feel worthy of being spoken, after encountering Baldwin’s brilliance. He speaks for himself, and to reduce his unapologetically true witness to an analytical datum is intellectual malpractice. Baldwin is braver than most. But I think it is time for American Jews to give everyone permission to speak as truly as James Baldwin about our history. It is time, in short, to let the Holocaust be history, which does not mean forgetting so much as remembering the past honestly as past. It is, to be sure, part of our history (among others’), but it must be history nonetheless, not an a-historical symbol of radical evil that we claim to own and deploy against those who, like Baldwin, question the politics of Jewish identity.

Maybe it is too much to claim that American Jewish community’s claim to proprietorship of the Holocaust stifles critical discourse. Or maybe it’s too little. In this space, I can sustain my claim only through anecdotes: Christian academics who read post-Holocaust Jewish thinkers with an unusually un-critical lens, students who hesitate to criticize American Jewish participation in systemic injustice. The fear, hard to put into words, that I feel even as I write this article, suggesting to me that to criticize how Jews memorialize the Holocaust is horrifyingly disloyal. That I don’t know enough; I wasn’t there, it isn’t my place to comment. Maybe these anecdotes don’t align with reality, and Holocaust remembrance is not as problematic as I perceive it to be. But I cannot shake the suspicion that Baldwin got it exactly right when he said that American Jews use the memory of the Holocaust “shamefully.”

To be clear, I think we should remember the Holocaust. We have to. But to remember the Holocaust without being critical about the political work that remembrance performs is something we cannot do. Quite the contrary, to allow the memory of the 6,000,000 to be reduced to a political talking point strikes me as horrifyingly disloyal. The historian Peter Novick suggests that “talk of uniqueness and incomparability surrounding the Holocaust…promotes evasion of moral and historical responsibility.” If this is true, then Baldwin is right that American Jewry uses the memory of the Holocaust to silence social and political criticisms of our community. That evasion is a betrayal both of the memory of Auschwitz and the ancient Jewish tradition of social justice.

We need to stop invoking Auschwitz to claim perpetual victimhood, because we are, to be blunt, no longer the worlds’ victims. American Jewry and the State of Israel need to give Auschwitz back to history, where it can stand alongside American slavery, the Armenian genocide, the Palestinian Nakba, South African apartheid, and others as catastrophic markers of modern history.

That emphatically does not mean that we should ignore the differences between these events, or draw any equivalence between them. But it does mean that we should not use one catastrophe (Auschwitz) to avoid acknowledging the fact that others have happened, and that we, as Jews, have sometimes been complicit in making them happen. Baldwin writes of how “galling” it is for a Jew to use his Jewishness as a cover for exploitative behavior. It should be “galling” for us, as Jews, for the Holocaust to become permission for evasion of responsibility.

Giving Auschwitz back to history doesn’t mean it can’t be important to Jewish life, but it does mean that the Holocaust is over. That means the end of “shamelessly [using the Holocaust] as proof we cannot be bigots,” which means giving people permission to criticize us as harshly and honestly as Baldwin did. That should also mean the end of equating any ostensible threat to Jewish people anywhere in the world with Hitler’s genocidal campaign. To be sure, there are threats, but the knee-jerk tendency to invoke the Holocaust whenever anything happens to a Jew anywhere serves only ideology, not history.

Holocaust memory does not belong to Benjamin Netanyahu, nor to the State of Israel nor to American Jewry. The Holocaust must belong to history, and though we must remember it, we should hesitate to refashion it in the image of our hegemonic politics. Baldwin’s voice must be heard by our community alongside Bibi’s, and his challenge must be felt deeply. If American Jewry wants to live up to our “liberal” street cred; if we want to recreate that mythical, golden age of the “Jewish-Black alliance” (which never really existed to begin with); if we want to remember the victims of the Holocaust honestly and rightly; if we want to be chosen, or unique, or special, then we have to give the unspeakable memory of Auschwitz back to history, instead of weaponizing it in our attempts to become just like everyone else. American Jewry must take responsibility for what we have become.

Evan Goldstein is a student at Boston College.