What do we call a society where you have to gain state permission before you can travel a few miles in order to marry?

Perhaps it seems that we are searching for an “-ism,” some grand unified theory that nobody without the letters Ph.D. after their name cares about. But as the New York Times reports, it is not necessary to grasp at abstractions; we can call such a society Israel. Now, readers of my posts (hi mom!) have probably noticed by now that I am a huge nerd. Specifically, a huge nerd for political theory and theology. So, since it’s Sunday as I write this, and I’m banking very hard on having a snow day tomorrow, let’s have some fun (“fun”) with this Times story. And by fun, I obviously mean, let’s consider what the political philosophy of Thomas Hobbes can tell us about Israel’s policies. For real, though, here’s my argument: Israel’s restriction of Palestinian movement reveals Israel’s political structure to be thoroughly Hobbesian and should, at a minimum, raise the question of whether a Hobbesian state can really be a Jewish state.

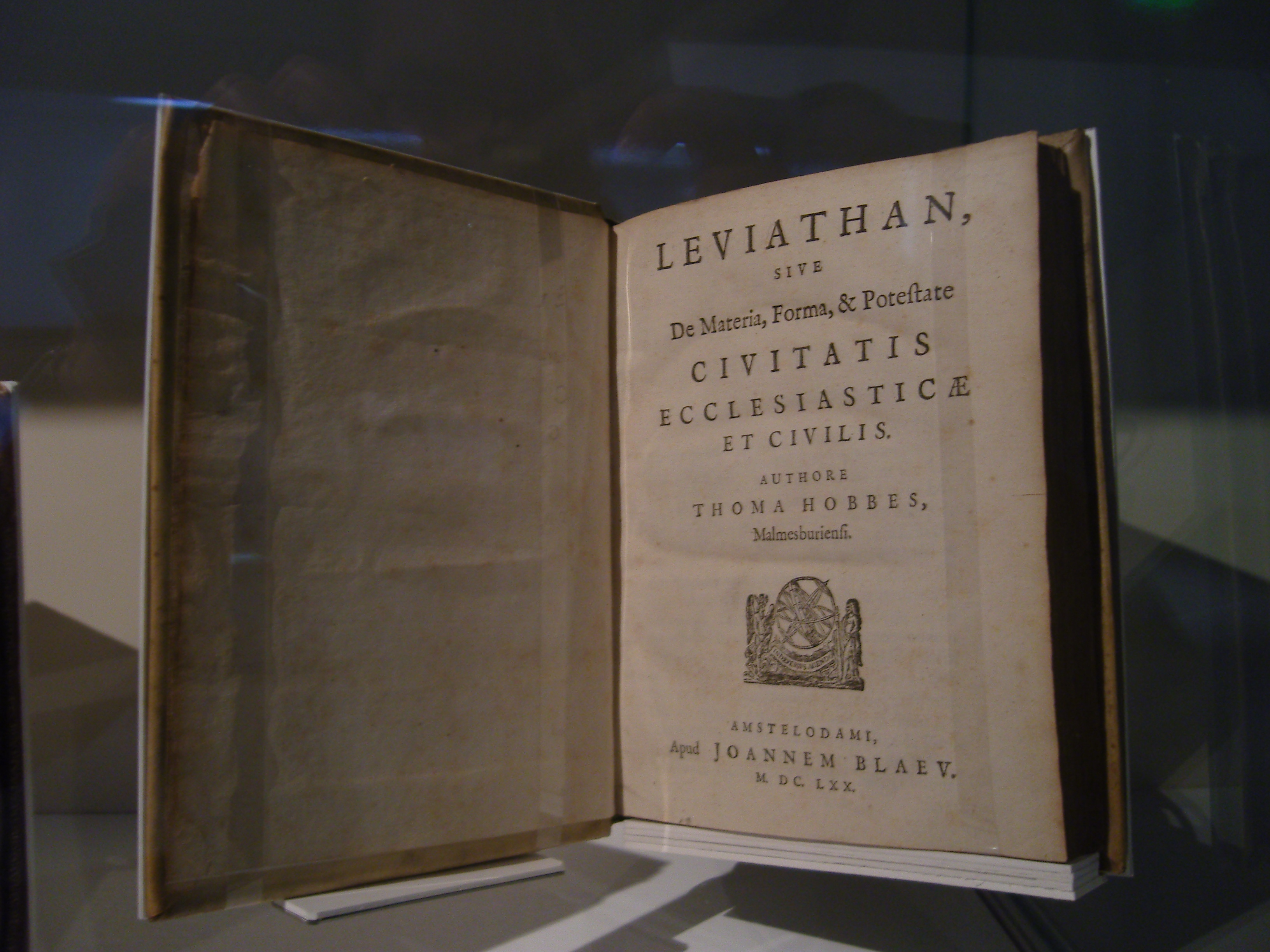

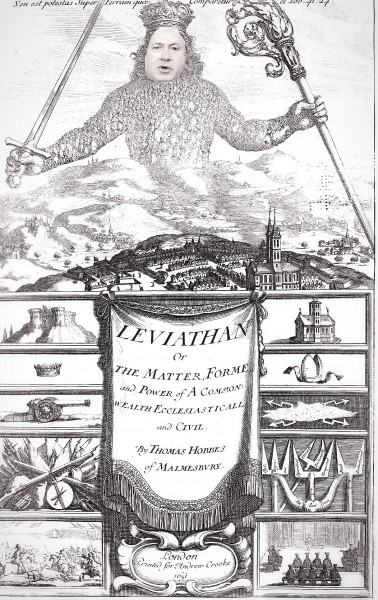

Perhaps Hobbes’ most famous idea is his oft-quoted description in Leviathan of the so-called state of nature: a war of “every man against every man [sic],” in which life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Therein lies the motivation for entering into a commonwealth: self-preservation. In other words, people form commonwealths so nobody will kill them. In order to guarantee that they won’t be killed, people cede their natural rights (which, in Hobbes’ view, is a right to literally everything, including killing another person and stealing all their stuff for no reason) to a “Sovereign,” who subsequently gives back to the people whatever rights can be given back without threatening the aforementioned imperative of not being abruptly ended. The Sovereign acts as the enforcer of laws, but is not herself subject to them, and the motto of the Hobbesian commonwealth is simple: Love it or leave it (or, perhaps better, “Obey or GTFO”). You can follow the laws or you venture out into the state of nature on your own, but if you choose not to follow the laws, the Sovereign can do literally anything to you and it’s totally kosher.

Hobbes’ thought contains two points that we now consider essential to modern politics: First, Hobbes presupposes the natural equality of humankind. Second, Hobbes uses a language we now find quite familiar: “rights” form the basis of his commonwealth. At the same time, Hobbes does away with the classical understanding of politics as a civil conversation in search of some highest good. There is no highest good in the Hobbesian configuration, only an ineradicable fear of death that can be mitigated only by assigning quasi-divine status (i.e., the Sovereign speaks and the law comes into being) to the head of the Commonwealth.

So what does this have to do with Israel? I want to suggest the Times piece demonstrates three Hobbesian aspects of the Israeli power apparatus: First, there is no greatest good, other than self-preservation. The quotation from the Israeli government spokeswoman is instructive in this regard: While she doesn’t directly point to Hamas and say, “this is why you, Palestinians trying to marry, can’t have nice things,” she basically does. An ostensible threat to Israeli self-preservation overrides the right of Palestinian citizens to see their beloved. Second, the Sovereign is the sole agent with the ability to assign or take away rights. While we tend to think of rights as irrevocable, Hobbes suggests that we give all of our rights to the Sovereign upon entering the commonwealth, and the Sovereign alone can give them back to us. Third, and perhaps most importantly, the Sovereign decides what a threat is. In other words, the Sovereign both exists to secure self-preservation and decides what things are existential threats. That’s the only way that we end up with a preposterous law like the one permitting Israel to deny Palestinians the right to marry. Does Palestinian marriage pose any actual, let alone existential, threat to the State of Israel? Of course not, and anyone who says it does is out of their mind. But while the Israeli government might have failed their basic compassion test, they would pass Thomas Hobbes’ political philosophy exam with flying colors, because they’ve figured it out: Politics isn’t about good, it’s about power. When you’ve got power, you get to decide what’s good, and everyone else can deal with it.

A few centuries later, the Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt found himself captivated by Hobbesian ideas. He suggested that politics is based upon the distinction between friend and enemy; the nation-state is always fighting someone, and that ever-present fight (against enemies real and imagined) is precisely what sustains the Sovereign’s legitimacy. The Sovereign, Schmitt famously put it, is the one who decides the exception. Who gets married, and who doesn’t? What shipments get in, and what ships get boarded? The one who decides those questions is the one with the power.

Don’t misunderstand me; I’m not saying Israel is the new Nazis (or that there are “new Nazis” at all; the Nazis were the Nazis and anyone who isn’t a Nazi isn’t a Nazi). My mention of Schmitt is only intended to demonstrate the horrific possibilities latent in Hobbes’ thought (and, by extension, Western political thought itself). But the real question I want to raise is this: Is Israel a Jewish state? If so, what is Jewish about it? And if not, what un-Jewish things (laws, actions, identities) have we come to call Jewish because of the State of Israel? In other words, if we can call a society where you need the state’s permission to marry “Israel,” in what sense can such a Hobbesian society be called “Jewish”?

Evan Goldstein is a student at Boston College.