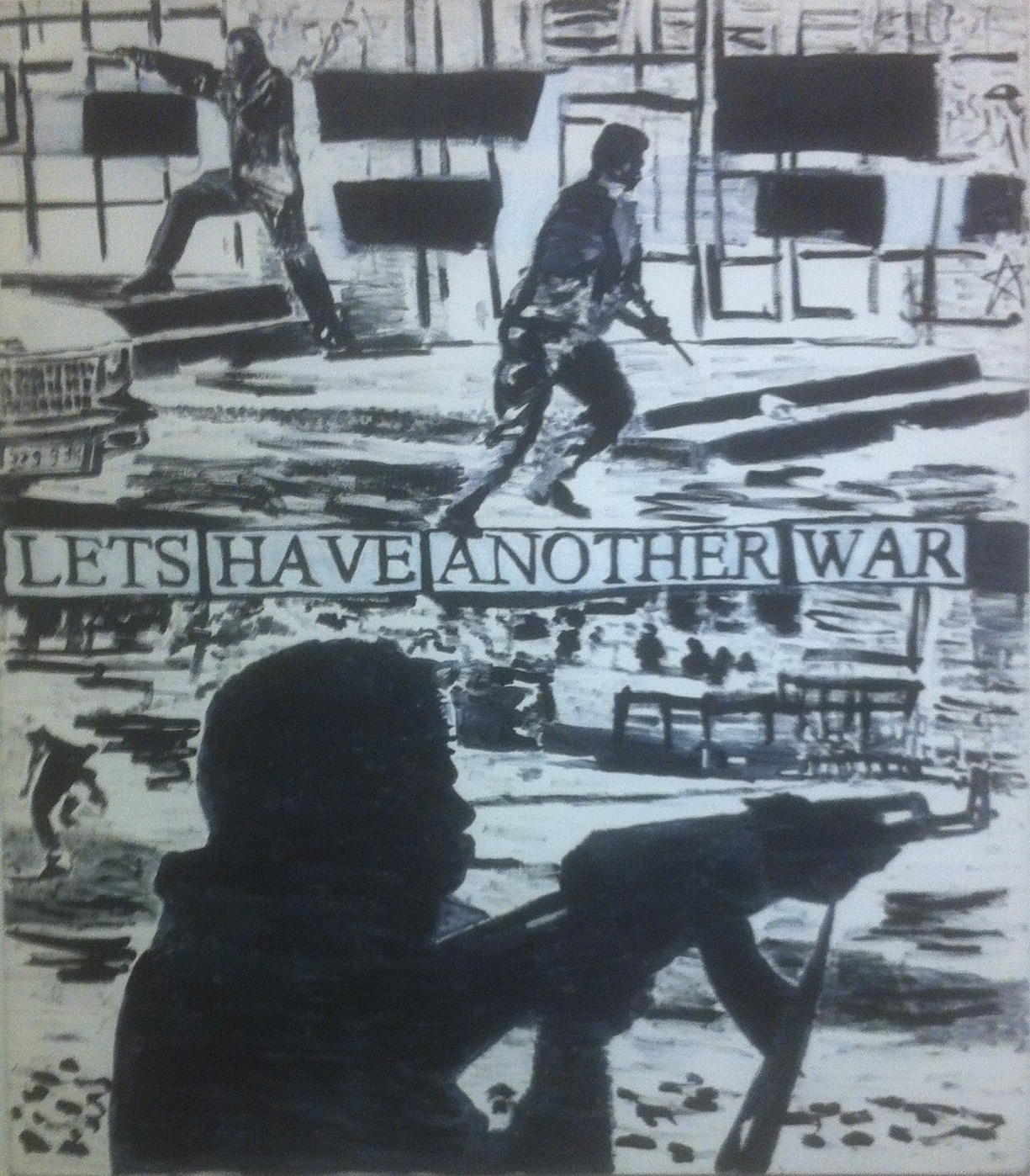

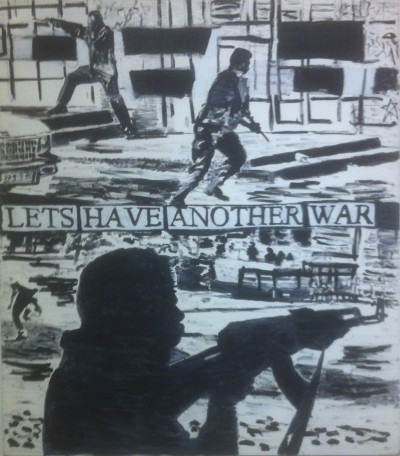

After a summer of war in Israel, David Reeb’s series, “Let’s Have Another War” is a powerful greeting as one enters the gallery at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Reeb places the text “Let’s Have Another War” as a constant caption throughout the series, a caption overlaid on top of gruesome images of war. Painted in 1977, Reeb’s acrylic black and white pieces ring eerily true nearly twenty years and many wars later, when the prayer on the lips of so many is for peace.

“Let’s Have Another War”1996, acrylic on canvas, 140×160

Reeb’s work is filled with numbers, letters, tangible forms to mark the intangible effects of constant war on a society. If you live in Israel, war is not an abstract concept or simply part of a painting. It is your reality, and it was very much Reeb’s, when he served in the Yom Kippur War. I think of this as I overhear a grandmother in the gallery teaching her grandson how to count by using number paintings which mark the years in which Reeb did not fight in wars. She doesn’t act as if she realizes the significance of the numbers, or maybe after a life in this country, one becomes numb to the numbers.

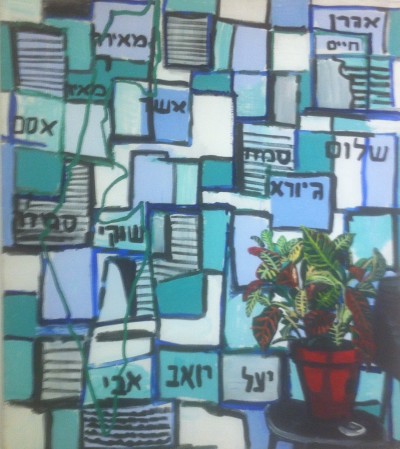

Reeb brings the facts of war to the forefront, beseeching his viewers to be jolted by its proximity. He uses text not only as a caption but as a form of stand-alone narrative. Large paintings use solely text to tell personal narratives of war. Next to these are paintings of biblical passages about wars with Midyan (Bamidbar 31) and conquering the Land of Israel (Joshua 8). Reeb paints abstractly and figuratively on top of these texts, illustrating a form of discomfort with war. Around the corner hangs Shemot, another painting named after a book of the Bible. But the names painted in the background are are not the names of the Israelites who descended to Egypt in the beginning of the Book of Exodus; rather, these are contemporary Israeli names, suggested by the superimposed map of Israel. The comparison between biblical Israel and the Israel of today is important to Reeb’s work, as he places past wars and present wars side by side, while all the time while the future hangs as a question.

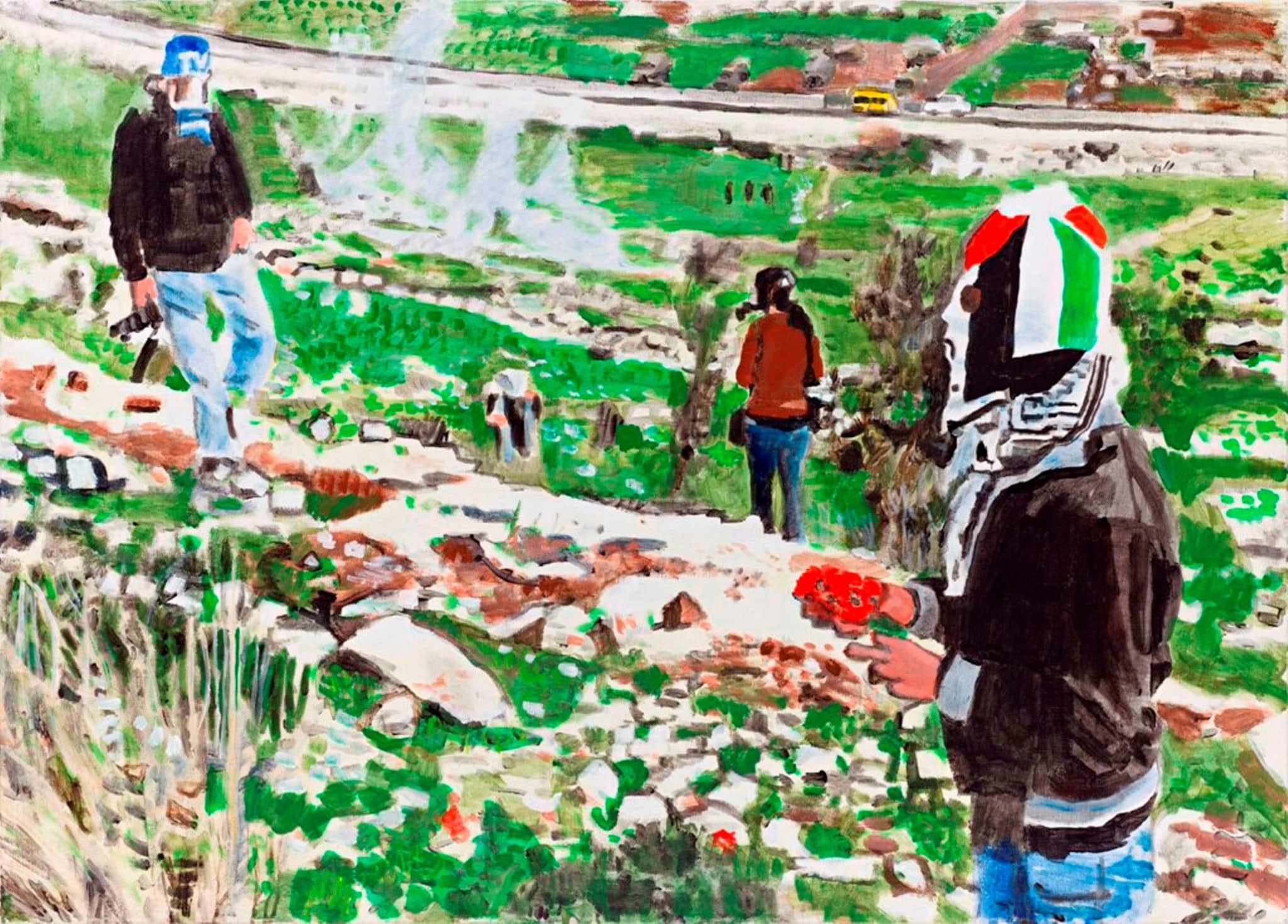

In the second half of the gallery, Reeb’s discomfort with what the future may bring is quite loud. The second half of the gallery is devoted to his project regarding protests in Ni’ilin, Bil’in, and Nabi Saleh against the Occupation. For this project, Reeb has shot footage every Friday since 2005 of the protests in these villages.

The experience of viewing these works is jarring. Watching the films, one sees violence from both sides. The Palestinian citizens throw stones, while Israeli soldiers fire shots in return. The citizens chant about ending the Occupation, while the soldiers force them back. For a moment, I forget that I am sitting in an art museum, and think I am watching a documentary. Then I remember I am in a museum, and the films, for a moment, seem fictional. Could this all really be occurring every Friday merely an hour’s drive away from the quiet of the gallery?

While rooms with videos display the footage, the rooms outside display paintings of the footage. While Reeb’s text paintings are poignant, his imagery hits close to home, not so far removed from its original source. The color paintings of the stills act almost like photographs, with selective pieces of editing, such as the accentuation with bold colors of a sign warning about electricity in Three Friends (Sakanat Mavet: Danger of Death!).

But for the most part, Reeb seems to be declaring an inability to edit or change what he has seen with his own eyes, what he has read in Biblical passages or today’s newspapers, demonstrating a close and personal relationship to this conflict, but also an unwillingness to tamper with the objectivity of war. The conflict begins to emerge in the character of the artist himself, as he oscillates between portraying his own experiences fighting for Israel and the experience of the other, protesting Israel’s existence. Any viewer cannot help but feel divided and conflicted, forced to acknowledge that with another war and another, being numb is hardly an option.

David Reeb: 48—60—300 is on view at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art through November 29. You can view his videos here.

Yael Roberts is a recent graduate of Stern College now attending the Pardes Institute for Jewish Studies in Jerusalem.