Like most Jews with ties to South Africa, my heritage is extremely Ashkenazi. In fact, both sides of my family largely originate from the same region of what is now northeastern Lithuania and northern Belarus. Growing up in New York, most of what I was exposed to as “Jewish culture” was really “Ashkenazi, specifically Lithuanian practice”: savory gefilte fish, Yiddishisms, and my grandmother’s frown at the mere mention of the word Chabad. (As almost every Litvak family does, we claim [perhaps incorrectly] that we are descended from the Vilna Ga’on, whose archenemy was the Hasidic movement.) Suffice to say that, in a country whose Jewish community equates “Jewish” and “Eastern European,” my Jewish upbringing was extremely Ashke-normative.

Some of this changed in college. I learned about Sephardi and Mizrahi customs and traditions – from the additions in the Kaddish to the foods consumed on various holidays. I learned particularly about the discrimination Mizrahi migrants faced in the early days of Israel, and about continued struggles in that regard today. However, my engagement with non-Ashkenazi custom by and large remained somewhat curtailed, and our Hillel was certainly very Ashkenazi-centric – despite the staff’s best efforts at inclusion.

And then I crossed the Atlantic.

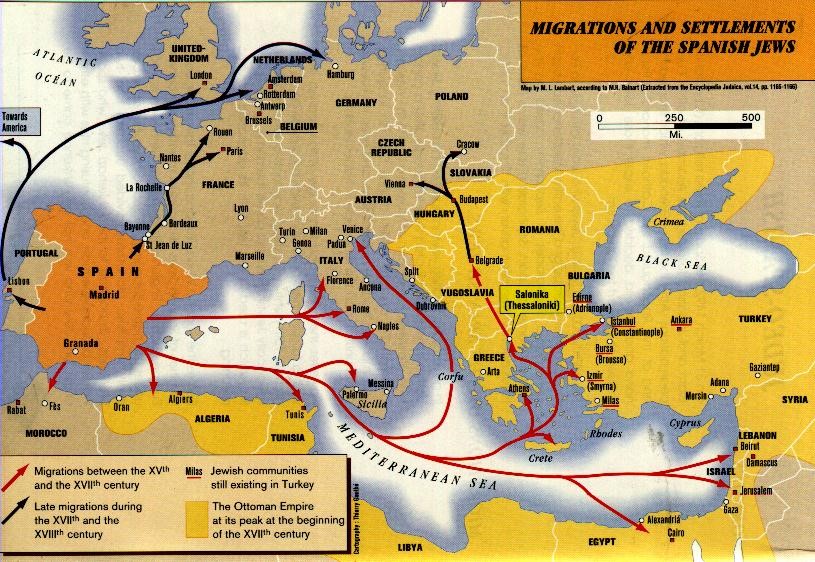

England’s Jewish community has a quite different hierarchy of custom. The first Jews allowed in the country after re-admission to England in the 17th century were Spanish and Portuguese Jews from Amsterdam. Their practice became the established norm in London by the 18th century, and wealthy Italian Jews contributed too to an ascendant Sephardi norm. True, some German custom was to be found. But by the arrival of large-scale Ashkenazi migration to England in the late 19th-century, an upper-class Anglo-Jewish Sephardi community had sealed Sephardi custom in the “upper-caste” practice of Jewry across the British Empire. Despite changes instituted by a huge Ashkenazi influx, many Sephardi traditions remain just as normative and celebrated in England – even as they are hushed in an America that exhibited a similar Jewish settlement trajectory.

Oxford’s (fantastic) community is, admittedly, somewhat more non-Ashkenazi than most English synagogues. Several of the prominent community members, prayer-leaders, and Torah readers are Sephardi or Mizrahi, and both practices are frequently found in services. There was even a Sephardi option on Yom Kippur. But beyond Oxford, Sephardi and Mizrahi influences can be found throughout English Jewish practice today. A distinct English Sephardic prayer rite is still used, and many siddurim offer both Ashkenazi and Sephardi options. Sephardic heroes in English Jewish history – Sir Moses Montefiore prime among them – are far more celebrated than those of America.

My initial reaction was one of puzzlement. “What are these strange practices?” I thought. “And how is everyone here not as puzzled as I am?” But I soon realized that my consideration of these practices as strange was a reflection of my own Ashkenazi-centric upbringing, and my own Ashkenazi-centric approach to Judaism. Rather than see these non-Ashkenazi practices as strange, or demand to be taught about them, I realized it was my imperative to learn more about them. At this point, I find myself now celebrating the change. After all, we are one people Israel.

Admittedly, England’s Jewish community is very Ashkenazi-normative too. (Other parts of the United Kingdom are too.) Many English Jews are also confused at their first encounter with Sephardi or Mizrahi practice. Yet in conversation I noticed that many more English Ashkenazim are comfortable with non-Ashkenazi practice than those in the United States. I began to wonder why.

New York may be big, but it is a bubble. So often in the big Jewish communities of the United States, “different” practices get isolated into their own spaces. Sephardim in New York go to Sephardi synagogues OR sit through a highly Ashkenazi practice. Note that few Ashkenazim go in the other direction. Simultaneously, ideas of normalcy in Jewish communities – and especially the traditional egalitarian communities I have participated in – hew towards a highly Ashkenazi-centric model. Some point out, rightly, that most American Jews are Ashkenazi. (So are most English Jews.) Others fall prey to racist ideas, claiming that Ashkenazim were somehow more egalitarian, or that Ashkenazi practice is the basis of Jewish achievement. Neither is true – and the self-congratulation allows us to forget that non-Ashkenazi practice has just as much of a place in Jewish worship today. England more generally and Oxford specifically offer one potential way forward in this regard: integration of practice is not all that impossible. But, beyond this, we must copy England in another manner: honoring Sephardi and Mizrahi custom.

As Sephardi-written articles in New Voices have said before, honoring Sephardi and Mizrahi custom as an Ashkenazi person is about more than eating mufletot, or appreciating the occasional chanting in Syrian or Gibraltarian tropes. One must learn about Sephardi and Mizrahi history – and certainly not in the “heroic Ashkenazi savior” mode. One must undo the conflation of Jewishness with Ashkenazikeit: for some Jews, matzoh balls are as foreign to their celebrations as fenugreek is to ours. And perhaps most importantly, one must become as ready to acknowledge Sephardi and Mizrahi practice as normative as one does Ashkenazi.

In that regard, we again can learn a lot from England.

Jonathan P. Katz is a grad student at Oxford University.