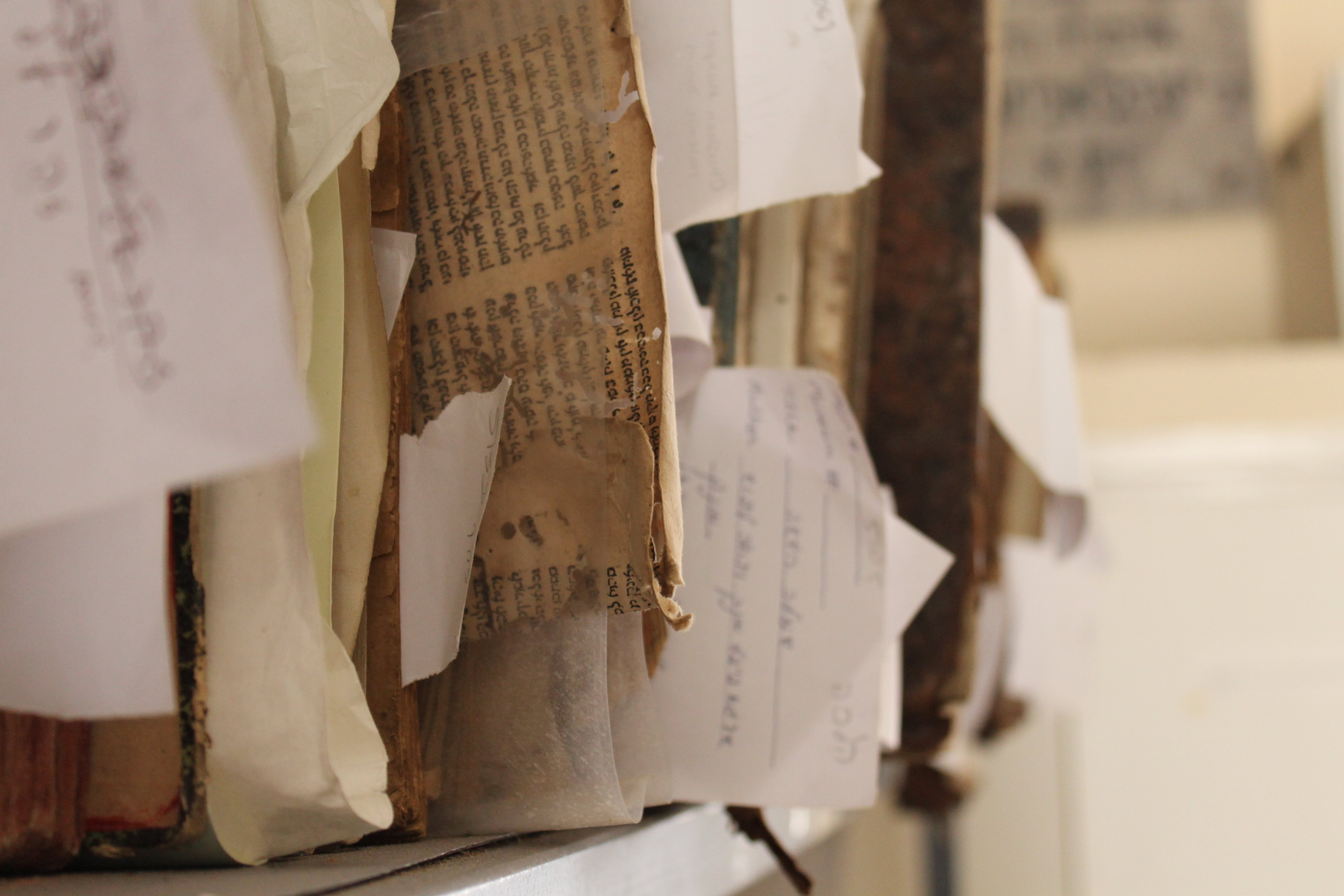

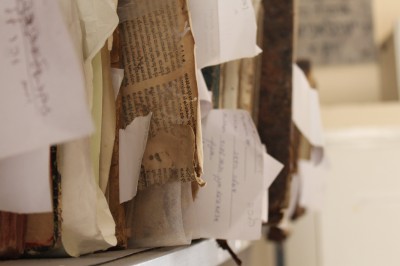

A storied community in a room. Hand-written notes, wedding documents, and Mezuzahs piled everywhere. When Oren Kosansky discovered these items and more in bags and boxes in a small room in the old synagogue of Rabat, Morocco as a Fulbright Scholar in 2005, they would change his life and the lives of his future students forever.

The room contained the community’s genizah, or place where Jewish documents containing the sacred Name of God such as books, letters, documents, and ritual items are kept until they can be properly buried in accordance with Jewish law.

Rabat had a strong Jewish community numbering in the thousands into the 20th century, when most Jews emigrated, primarily to Israel and France. Today, Morocco’s capital contains fewer than 100 Jews. In their genizah, the community left behind an invaluable record of hundreds of documents and artifacts in Hebrew, Arabic, French, Judeo-Arabic, Aramaic, Spanish, Judeo-Spanish, Russian, and even English, dating back as far as the 18th century, that powerfully tell the story of the life of a lost community in its own words.

In 2010, Kosansky, now a professor at Lewis and Clark College in Portland, Ore., won a $50,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to establish The Rabat Genizah Project in collaboration with the Morocco Jewish Museum in Casablanca– the only Jewish museum in the Arab world.

The project aims to scan and catalog every unique item in the genizah, translate it into Modern Hebrew, English, and Arabic, and make it fully available and searchable for free online for anyone to access. Kosansky has given his undergraduate students crucial roles in the project from the very start.

Hannah McCain was a junior religious studies major at Lewis and Clark in 2011 when she went to Kosansky’s office to speak with him about the class of his she was in. Eventually, they found themselves discussing summer plans. When McCain mentioned she would be returning to Morocco, where she had studied abroad the previous summer, he asked if she spoke French; when she answered in the affirmative, he offered her the opportunity to join him on the project. “I respected Oren immensely, so I signed on immediately, basically before I even knew the details,” she said.

In Morocco, she joined Samantha Stein and Gabriella Tzvia Weiniger. Stein had just graduated from Lewis and Clark in the summer of 2011, and her interest in languages and the history of Jewish-Muslim relations made her the natural choice to be Kosansky’s research assistant.

Weiniger did research at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London with a focus on studying minorities and persecuted peoples with a special emphasis on Sephardic Jewish communities. She and Stein were friends, and Stein knew this project would be perfect for her.

As a team, they spent the summer scanning every document and making a record of its author, language, title, and year to make them easily accessible via database. Stein and Weiniger translated the Hebrew and Arabic texts, and McCain translated the French ones. Or, as Weiniger described it, “Basically, [it was] a lot of … scanning and a lot of ‘Oh wow, look at this document, it is so old/pretty/falling apart!’”

That summer was just the beginning. This summer, Maia Erickson, an incoming senior at Lewis and Clark studying cross-cultural conflict studies, will bring the project into a whole new phase. In addition to using her knowledge of French and Arabic to translate and digitize archives like her predecessors, she will also work with Vanessa Paloma, an ethnomusicologist and musician living in Casablanca, who has been recording music and oral histories of Jews in Morocco. Erickson will help Paloma structure her data into an inventory system based on that of the genizah, giving her the potential to mount her recordings in a similar online archive. “This is a perfect example of what we hope the impact will be of the Rabat Genizah Project–not only a source of information about the genizah collection, but a resource for other scholars as well,” Erickson said.

For Stein, expanding the use of technologies that have made this project possible–such as inexpensive high-resolution scanners and open-source cloud computing– have exciting implications for preserving history all over the world. “Everything we do today creates a digital archive, and this adds to it,” she said. “What we do here will help catalog the past and make it free for anyone to access and comment on.”

As a non-Jew with a passion for study of the Abrahamic faiths, McCain found the experience of exploring the dual existence of Moroccan Jews rewarding, saying “It’s fascinating and also a bit sad to comprehend the loss of a substantial Jewish minority in Morocco — a whole piece of Moroccan society and culture, really. That’s why it’s so important to have things like the [genizah] that document that once-robust presence.”

The student participation is not limited to Rabat. According to Kosansky, under agreement with the Morocco Jewish Museum, about 10% of the archive has been taken back to the university to be scanned and cataloged by students there. After it is archived, it will be sent back to the Jewish Museum in Casablanca.

Kosansky is deeply aware of the significance of his students’ contributions to the project. He called McCain “instrumental” in managing daily operations of the project in Casablanca and noted the “particularly important role” she played in translating documents from French.

He went on to praise the “enterprising spirit” Stein brought to the project, especially in its early stages. “She was not merely a student assistant. She was a partner in the creation the digital enterprise itself,” he said.

But he is also quick to note that you don’t have to know multiple languages to be involved in an important project. He emphasizes that all students can benefit from the “further development of language skills, opportunities to work alongside professional scholars… [and] valuable experience with digital technologies that are transforming contemporary scholarship in the social sciences and humanities” that such projects provide.

His students agree that this just one of many opportunities for student involvement in important research projects all over the world.

“You realize as a student that … you can do something important and you’ll find your professors are very supportive,” Stein said. For her, persistence is the key. “These days, you can’t have a degree and expect a job. You must be proactive, figure out what opportunities are out there, and who can help you get there, and if they say no, change your approach. If you want to make something happen, make it happen. If you’re not qualified, learn what you need to be qualified. Email people in positions you find interesting, and if they don’t respond, email 10 more times. It is easiest to do this as a student since you have nothing to lose.”

The feeling of involvement can be addictive. “The challenging part was leaving Morocco knowing there was so much more to do!” Weiniger said. “Even if someone else has discovered [something], you can add a new interpretation, see something completely different, or even come to the exact opposite conclusion. … Find something undiscovered, expose it, look at its vast implications, and sew another patch on the quilt of human history.”

.

.

Derek M. Kwait graduated from the University of Pittsburgh and is editor in chief of New Voices.