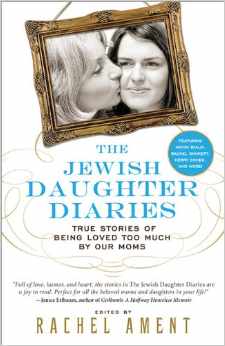

I must have told my mother one too many times that she embodies the Jewish Mother stereotype. (She really does, by the way. Ask, as one example, the ten cast and crew members of a show I worked on in high school for whom my mother provided enough food for forty people, lest anyone starve to death in suburban Pittsburgh.) She must have been fed up, or more likely anxious, that I kept branding her a Jewish Mother, because after my umpteenth comment, she finally responded, “But I’m not like other Jewish Mothers, right? I’m a cool Jewish Mom, right?” Unintentional Mean Girls reference or not, this desperate question made me wonder why exactly my mother felt a need to add an addendum to the title “Jewish Mother” unless being one was not a positive thing. After this conversation occurred, I myself experienced a dark side of the stereotype, as I’ve written about, when a subconscious need to embody it made any dormant neuroses I might have had reveal themselves in Technicolor. Perpetrating these stereotypes, then, is problematic to me, and I was worried, therefore, that The Jewish Daughter Diaries, Rachel Ament’s anthology of women’s experiences with their Jewish mothers or grandmothers would do just that.

I was immensely and pleasantly surprised, therefore, when, in the introduction, Ament writes, “A Jewish mom is not a one-size fits all archetype,” and that the aim of her project is merely to enrich others’ lives with charming, touching, funny, or otherwise enriching stories of experiences with Jewish mothers or grandmothers. In reading them, I found that the character of each featured Jewish woman, far from recapitulating only vaguely relevant generalizations, varied immensely. Many, it seemed, actually actively debunked these generalization. For instance, Rachel Shukert’s “Ominous Pronunciations of Doom” begins “My mother always prided herself on not being the typical Jewish mother,” and Mara Altman’s “Jewish Mom Genes” tells the story of a mother who exemplifies the opposite of stereotype. In other essays, authors focus on more stereotypical Jewish Mother characteristics, such as neuroses or a nosy desire for their daughters to marry. But while the essays might have acknowledged the stereotype, the authors always placed the quirks into the context of a woman. I never felt like I was reading about Jewish mothers as much as about particular mothers that happened to be Jewish, and that is exceedingly refreshing.

Yet, though each essay presents a story unique to the woman it features, I somehow found something very familiar in each of them. True, some mothers had personalities and habits that more closely matched my mother’s, but I felt like I could relate even to the stories for which this wasn’t the case, like I found something of my relationship with my own mother in them. Reflecting on this after reading the book, I remembered something else Ament wrote in the introduction: “What makes a Jewish mother stand out is not the degree of her love, but how her love materializes. Love suffuses a Jewish mom’s every thought, her every behavior.” Perhaps this too is a stereotype, or perhaps this is something that is not actually unique to Jews. But it is at least in many cases true and something that The Jewish Daughter Diaries captures well. Though she expresses it in odd or eclectic ways, each mother written about obviously bursts with love for her daughter or granddaughter. When a book is full so much love, a reader can’t help but feel it too.

Dani Plung is a student at the University of Chicago.