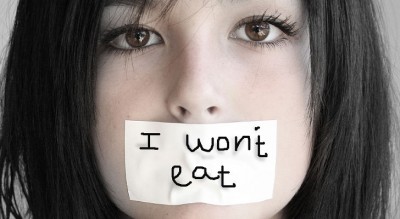

Third grade lunch at Solomon Schechter Jewish Day School. All my friends are sitting around eating Cheetos and sharing sandwiches. Me, I’m staring at the clock waiting for the little and the big hand to both land on the twelve so that I can throw the untouched lunch my mother packed me into the trash can. For as long as I can remember I have had an aversion to food, which is funny since almost all of my memories from childhood include food. When I look back and think about holidays I spent surrounded by family, I think about how many Rosh Hashanahs at my zaida’s house I spent saying I don’t like apples and honey, how many Hannukahs I refused to eat latkes, and how many Purims I convinced myself I didn’t like Hamantashen. I don’t remember the discussions we had at the table, but I do remember the anxiety I felt about eating the meal in front of me. I love being Jewish, I have always felt that it is one of things about me that makes me special. But there is another thing about me that has always made me special—anorexia.

These early memories of food and Judaism are just the beginning of a life filled with memories of feeling pride in starvation. Food, or lack of it, has taken me down a long, dark road that is now slowly turning upward. It started with throwing my lunch out in elementary school. Then skipping dinner the 3 nights a week I had dance in middle school. By high school I was eating under 800 calories a day, and by the start of college 500. By the time I sought treatment I was living only on caffeine. I know this sounds implausible to those of you without an eating disorder, but it’s not like people didn’t notice. I lost weight, then when people got too concerned, gained it back only to lose all of it and more again. I honestly have no idea what started my eating disorder. I do, however, know why it took me so long to seek treatment. Anorexia served as a protector for me. I needed nothing and no one. Nobody could hurt me more than I could hurt myself. I created a wall between me and the rest of the world through anorexia. The big problem started, though, in college when starvation was no longer enough to protect me from the world.

Going into college I was eager to get away from home. In the months leading up to it, my parents had separated and my aunt passed away from a short but painful fight with cancer. I felt like I had no control over anything in my life. The eating disorder was all I had control over, and I was going to control it to the fullest extent possible. The world continued to fall around me. I gave off an “I don’t care about myself” vibe, getting me into several bad relationships with boys and killing my self-esteem. My parents’ separation turned into a divorce. My eating disorder got worse. I stopped eating all together. When I was hungry I got a Starbucks. Then I cut out Starbucks, and from then on when I was hungry I drank a Monster energy drink.

One of the side effects of malnutrition is being unable to regulate emotions. I turned into an angry person. Someone who was so mad at the world that my only means of communication were starving and screaming. I was depressed and scared. My friends and my therapist grew increasingly concerned and began suggesting that I might need a higher level of care. They said my anorexia had gotten so severe that if I really wanted to live a happy life free from my eating disorder I would need to go to a residential treatment center. I adamantly objected, giving them a bunch of reasons why I could never go: I would miss too much work. My parents won’t pay for it. I would get too behind in school.

One day after a particularly miserable week, my therapist and I had the discussion about going residential for the millionth time, but this time I considered it—I was tired of being depressed, angry, and guarded. I left that session thinking, ‘Am I really that sick?’ For the first time my answer surprised me. ‘Yes.’ If I was being honest with myself, I was that sick. I was self-destructing and didn’t know how to stop. I had turned into a person I didn’t recognize. I began to invalidate every excuse I had not to go to treatment. I could take time off work, if I told my parents that I needed residential treatment to live they would pay for it, and I could take a medical leave from school—after all what use is a degree if I’m dead?

Three weeks later, I checked into Renfrew Philadelphia, an eating disorder residential treatment center. Treatment was not easy, and at the beginning I fought very hard against working through the underlying issues that my eating disorder was protecting me from. A week passed, and Shabbat arrived. Thirteen percent of the population at Renfrew identifies as Jewish so several of us had an interest in celebrating. Another Jewish girl and I decided we wanted to light candles. The Center gave us electronic candles because fire was not allowed. We turned them on and said the blessing. After candle lighting, it was time for dinner. Our psychiatrist had arranged for there to be challah and grape juice for us to say blessings over. We left the dining hall, said Kiddush, washed our hands, and then stared at the challah. It was time for Motzi. We looked at each other nervously knowing that if we said Motzi we would have to eat some of the challah. We decided we would say it in unison and then eat the challah together. We said Motzi, took a bite of bread, and then I realized something—this was the first time in years that I actually said Motzi and meant it. Moreover, this was the first time in years I took a bight of challah, and this was the first time in years I completed the ritual in its entirety. I sat down for dinner and finished my whole plate. It was the first meal in treatment I completed. The first meal of recovery. After dinner, the other Jewish girls and I decided to say the Blessing After Meals. I ate a meal! I could actually bentch! For the first time in a long time I was thankful for the food in front of me. I was thankful for eating. I was proud. The Shabbats that followed included the same rituals, but each time we grew less and less hesitant to say Motzi. Instead of eating a tiny bight of challah we began to eat pieces. By my last week there we were eating the whole challah together. Rather than a day I dreaded, Shabbat became a time I looked forward to. A time I recognized all the progress I made in the past week. The challah became symbolic. At first I was hesitant to recover so I only took a crumb’s worth of bread. As the weeks went on, I became less and less hesitant—I started to think recovery was what I really wanted. By the last week in treatment eating the whole challah symbolized that I knew I wanted recovery. I knew I was willing to start fighting for my life.

Jourdan Stein is a student at Drexel University.