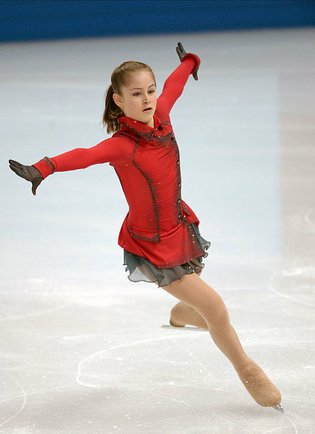

Bloggers made much ado as Julia Lipnitskaia took to the ice in the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi.

It wasn’t because she was one of the best figure skaters in the world at only 15 years old.

It wasn’t that in Lipnitskaia Russia had a representative on the rink for the first time in 10 years who wasn’t wielding a hockey stick.

It was because she decided to wear a red coat and dance to John Williams’ Oscar-winning score from Schindler’s List.

Israeli violinist Itzhak Perlman’s masterful performance underscores Steven Spielberg’s 1993 Holocaust blockbuster based on the true story of a German businessman, Oskar Schindler (played by Liam Neeson), who saves thousands of Jews from death by employing them in his factories.

Of the movie’s more memorable motifs is the single spot of color in an otherwise black-and-white film. As Nazis liquidate the Krakow ghetto, a girl in a red coat makes her way through the crowd and finds a hiding place.

Viewers see the coat one more time toward the end of the film on a cart filled with the corpses of the Nazis’ victims.

Lipnitskaia’s routine reimagines that motif, and the story of the Holocaust, as a figure skating routine, dressed in an outfit remembering that red coat.

Before she competed in the Sochi Olympics, her decision (not her performance) was criticized by Slate, PolicyMic, BBC and others.

The performance is called “controversial,” “pretty offensive,” “kitsch of the highest order,” and Slate accused her of using “material that she probably has no right using in the first place.”

Commentators of the blogosphere deigned the performance inappropriate because they did not want the Holocaust lessened. But they were wrong; Lipnitskaia supplements the canon of art about the Shoah rather than trivializing a tragic moment in world history.

If Lipnitskaia’s performance is inappropriate, then anything other than straightforward facts about the Holocaust, according to these commentators, should be forbidden.

If art is meant to force its viewers to struggle with complex emotions, what is the difference between Spielberg’s use of Schindler’s List to make money and Lipnitskaia’s use of the movie’s theme to win points? Would these same commentators condemn Everything is Illuminated, a Holocaust movie that also contains some of the most brilliant comedy I’ve ever seen? Should libraries pull Phillip Roth’s Plot Against America off the shelves for altering the history of the Holocaust? Should Ballet Austin have shut down Light, a ballet that showcased the beauty of humanity and its suffering during the Holocaust? Should American University, my school, have shut down a children’s musical about the Holocaust (of which I was a cast member) because it originally had a song about cheese?

When did political correctness force us to lose our humanity, our ability to recognize art for what it is: defiance of people like the Nazis who preferred a world of hatred and death?

The wounds of the Holocaust are still raw for the entire Jewish community, including myself. My great-great grandparents perished in it alongside millions more. Survivors have acted as mentors in my life, and I count their role in my life as a blessing. I can’t look at a picture of Adolf Hitler without my blood boiling. It is understandable that the Jewish community would guard against overt reduction of such a terrible time in world history.

No, figure skating cannot possibly capture the deep emotions of the Holocaust. But that doesn’t mean it should be off limits. Any addition to our understanding of the Shoah contributes to our goal to “never forget.” So we remember in any way we can.

The final spin, like the rest of Lipnitskaia’s work, is transcendent, as she rises in the last moments. This metaphorical triumph of the human spirit is a lesson of the Holocaust we should all appreciate. The Holocaust was a tragedy, and our ability to inspire hope in its wake through our art is our victory .

Zach C. Cohen is a student at American University.