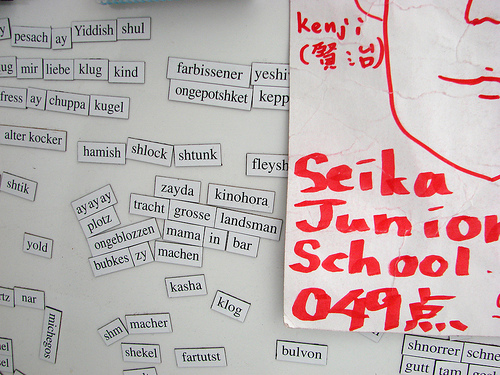

Yiddish is my favorite class. This isn’t new information, I’m sure; I’ve written about it on several occasions, including a piece entitled “On Why I Take Yiddish.” I furthermore use Yiddish allusions and colloquialisms as a matter of practice—in writing as well as in general conversation—so I’m sure my new found passion for the language is not a secret. In “On Why I Take Yiddish,” I noted that, for me, Yiddish is a way to connect to my roots—and this is absolutely true. All of my great-grandparents spoke Yiddish, some of my grandparents recall speaking it around their childhood houses as well, and last week, in a fit of procrastination, I found the small Lithuanian village from which my paternal great-grandfather emigrated by Googleing its Yiddish name (“Plotel,” for the record).

In my previous article, however, I also mentioned that, for me, Yiddishkeit was a way to connect with my Jewish identity, both because it was the language my ancestors spoke, and because, I think, at least in the United States, Yiddish culture has become synonymous with so-called “Cultural Judaism.” Several weeks after publishing that piece, Max Daniel responded with an equally well-written one, with the opinion that perhaps this way of thinking devalues, or makes more difficult the notion of klal yisrael, Jewish unity, in that we are limiting ourselves to valuing only that form of Jewishness to which we feel an immediate, palpable connection. Having stewed over this for a few months, I think I am now more inclined to agree with him.

I heard someone mention recently that Yiddish could perhaps be a linguistic method of connecting to Judaism, an alternative to Modern Hebrew, which some view as too thoroughly linked with Zionism for their comfort. After all, for those of us who are Ashkenazi, this is the language our ancestors spoke, thoughts of whom always seem to evoke deep feelings of Jewishness. There are a few fundamental differences, however, between the ways those Jews in der alter heym–or the “old country”–were able to connect with being Jewish and the ways we can. For one thing, the only other Jews that they knew or associated with were also Ashkenazi. Therefore, as far as many of them were concerned, Ashkenazi Judaism was the only Jewish culture, and therefore, Yiddish the only Jewish language. Furthermore, Jews in Eastern Europe were always the persecuted minority, the so-called “other,” so of course they would be bound together culturally and linguistically—assimilation was not an option.

But American Jews are in a different situation today. Not only do we now know of Jews who come from Sephardi, Mizrahi, or other roots, many of us actually belong to those categories. While we are still a minority and maybe sometimes “the other,” I would argue that we are not an oppressed minority—certainly not compared to Jews in Eastern Europe. Now that our definition of what it means to be Jewish is fundamentally different, our notions of Jewish culture must also be different. It doesn’t, for instance, make sense that in a thoroughly pluralistic Jewish society, our notion of “Jewish culture” is one reflective of the historical culture of a specific subset of that society. Nor should a cultural language of the entire society come from that subset

What, then, is the linguistic alternative? The closest thing I think we have to a Jewish Esperanto is Modern Hebrew. Again, however, because of the circumstances of its inception and its close ties to Zionism, some Diaspora Jews find identifying with the language problematic. Perhaps then, there is not a linguistic solution to a universal Jewish identity. Perhaps there is no such thing as a universal Jewish identity. But if there is, maybe language is not the way to pursue it.

While I still love Yiddish and Yiddish culture, my fundamental conceptions of why I do and what they mean to me have changed. Now, I hold that the language and the culture are ways for me to connect to my personal familial roots, rather than to Jewishness as a whole.

Dani Plung is a student at the University of Chicago.