I am a product of thirteen years of primary, elementary, and secondary Jewish day school education. I’ve been enrolled in a Jewish day school since I was three years old, and the idea of starting my school day at nine in the morning and ending at 2:30 in the afternoon is totally foreign to me.

Having been in day school for so long (and having attended three different day schools over the course of my career) has allowed me to see a wide number of problems. Jewish education is prohibitively expensive, and I realize the intense sacrifice that my parents made — and continue to make — to put my younger brothers and I through day school before college. I also realize the generosity of others who enabled my schools to give me the financial aid that I needed to continue attending. Especially while I was in high school, and was very turned off to various Jewish rituals, particularly prayer, it would seem like day school education was lost on me.

But it wasn’t.

A blog post in the Jewish Telegraphic Agency published last week explains one father’s reluctance to send his children to their Jewish day school. He claims that he and his wife both work in Jewish education and are better equipped to educate their children than are day schools. They also cite the (acknowledged) high costs of formal Jewish education, especially through twelfth grade.

I don’t doubt the author and his wife’s skills as educators.But having been through the day school system, looking back, I can now see the tremendous value in my Jewish education.

My Jewish education was more than just learning Talmud or Tanakh — there was a sense of community involved. For nine hours a day, I was surrounded by people who were learning the same texts that I was, and who were, like me, learning to question those texts. True, in high school, I was extremely cynical about my Judaism, and spent the better part of those four years rebelling against communal Jewish life. I was all too happy to trade in my early mornings spent in synagogue on Shabbat for an opportunity to sleep in, especially given the fact that I commuted for three hours a day to and from my home in southern Brooklyn.

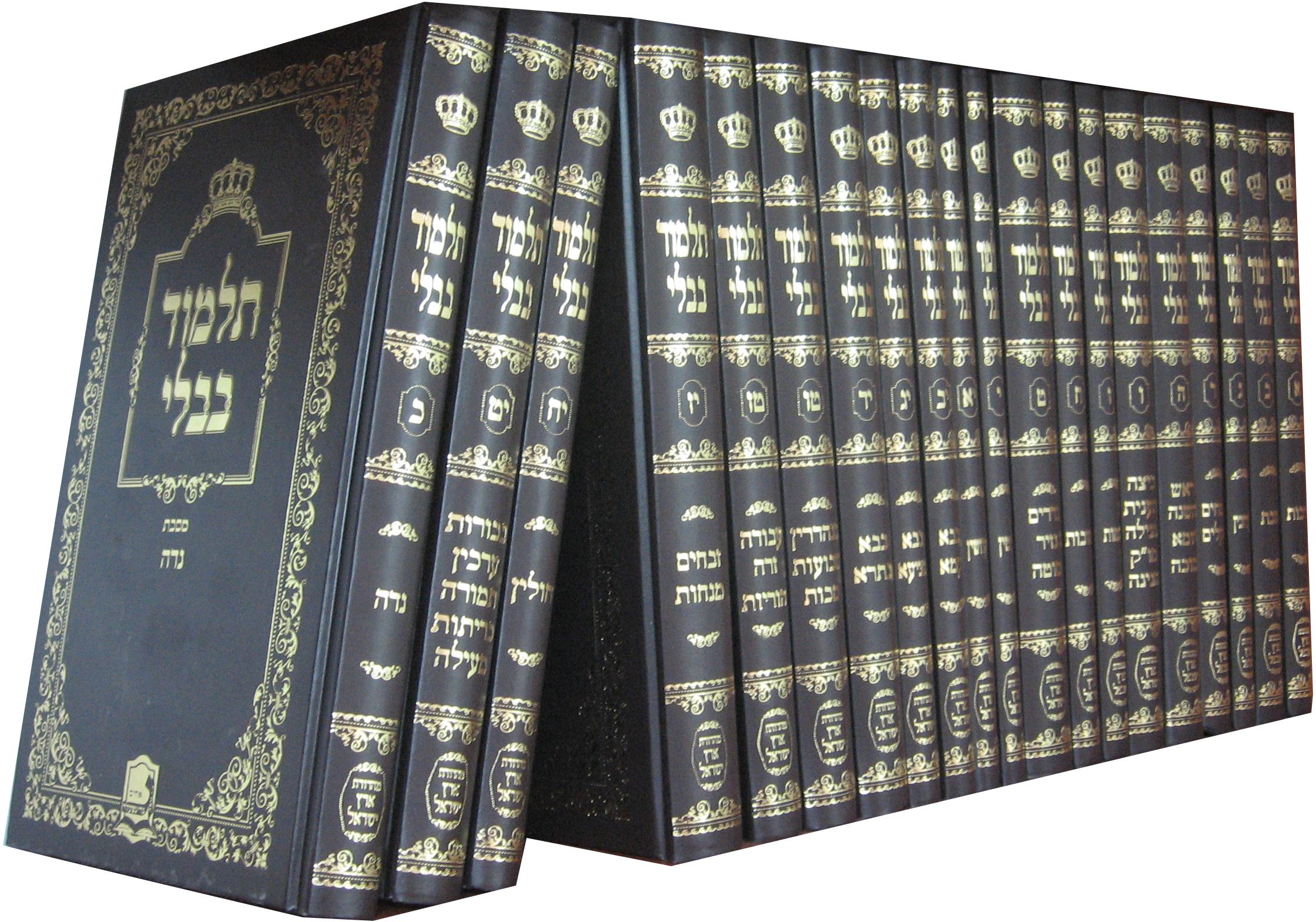

However, to be cynical, I needed to have something to be cynical about and have the background to downplay it. I was very skeptical about studying Talmud, for example. How could a bunch of rabbis, writing in the sixth century CE in yeshivoth in Ancient Babylonia with a completely wrong understanding of science have their writing still considered valid in today’s society?

Through studying those texts, however, I was instilled with a curiosity. I needed to understand the texts I was attacking. To provide a backing for a Judaism that, to me, is the truest representation of what the rabbis might have imagined had they been alive today, and not 1500 years prior, I need to understand their rationale in the present. If I want to be a Jew steeped in tradition, but also committed to progress and modernity, I need to understand both — and I would never have had the chance to study those texts if not for my Jewish education

I also needed a community of people who were just as cynical, and just as intellectually curious as I was. I needed a community of fellow students who were as willing to strike down the text, to throw out equally outrageous examples while still using Talmudic logic. That community of people who wanted to engage with the texts was something that drove me to apply to the Jewish Theological Seminary for college, wherein I would be able to continue engaging with those texts in a serious way, and seek to apply them to my life, thousands of years after some of them were redacted.

My Jewish education was not wasted on me. True, there is much that needs to be fixed. There is more that educators could have done to engage me, and the Jewish community should be doing more to provide affordable Jewish education that could target a wider number of Jewish children (there has been one petition circulating about the Internet recently that asks for Birthright to stop funding free trips to Israel, and, instead, to begin funding universal Jewish education for Jewish children). Perhaps Jewish educators should be finding new and engaging ways to integrate ancient Jewish texts into ways that can be applied today, to provide a lens through which we can see the problems plaguing our society — Mechon Hadar’s winter learning seminar for college students on Jewish food ethics last month is but one prime example.

The times when I felt unsatisfied with my Jewish education and what I was being taught instilled within me the curiosity to delve deeper beneath the surface of the texts, and to begin to understand what the rabbis of old were thinking, and how that pertains to me today. It drives me to continue studying today, both inside of school and out. If not for Jewish education, I would be completely lost to religion.

Amram Altzman is a student at List College.