My 21st birthday was on Yom Kippur. No, this isn’t the set-up of some Woody Allen-esque joke, but my real life (which often takes its cues from Annie Hall and Manhattan). When I mention this to people who ask me about my birthday plans, I always joke about it – how I could have a break-fast party with a shot of beer and get everyone black-out drunk, or how I wouldn’t even go to a bar at midnight if I wanted since most of my friends are Yom Kippur-observant Jews. Whatever the case, I didn’t think too much about it aside from being mildly amused and marginally disappointed. I already knew I was going to fast and attend services this year.

However, I began to feel uneasy and uncertain about my choice. Why should I bother with something that happens every year – something that I have trouble with theologically, to boot – and let it eclipse a coming-of-age event that happens once in a lifetime? But do I really want to start out my “adult” life turning my back on the holiest day of the year for a people and religion that I feel profoundly connected to? I was surprised that I was even entertaining the notion of foregoing Neilah in favor of an old-fashioned.

During one of the long-winded prayers that never seem to end, I mulled over this problem and found myself angry and jealous. Yom Kippur was stealing my birthday from me. And not just any birthday – the last birthday that anyone cares about until you turn 100 and get a letter from the president. Here I was, fasting to atone for my faults, apologizing for being a bad person, and promising to be better on the one day society allows me to be selfish and self-indulgent.

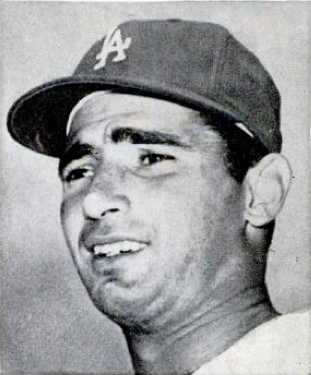

However, I soon realized a profound truth about who I am and who I want to be as an adult. I realized that this seemingly juvenile dilemma was emblematic of the struggle of being a Jew in the modern world. I was pulled by a commitment to my Jewish community and heritage, but also by a spirit of American individualism and independence. I wanted both and I wanted to embody both and –if the successes of modern Jewry are any indication – I could. But what about when you enter into alcohol-drinking and comedy-club-admitting adulthood on the most sacred day in the Jewish year? There was no practical (or safe) way to engage in both. I was reminded of the oft-told tale of how Sandy Koufax refused to play Game 1 of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur.

If I identified solely as a Jew, I would have no qualms about turning 21 on Yom Kippur. Clearly, the holiest day of the year when God inscribes me in the Book of Life (I hope) is infinitely more important than chugging Natty Light behind a highlight reel of last weeks Patriots game. But if I identified solely as an American, what would oblige me to fast and pray, especially on the day I’m invited to embrace and flaunt extravagance and licentiousness?

But I am and want to remain an American Jew, and could discuss in length and detail about how much I love it. Thus a dilemma is born. On one end is the holiest day of the year for my ancestral folk, a day of fasting, repentance, and all-around deep religious conviction. On the other end is the day I effectively enter the American social scene and, especially in New York City, a whole new world opens up (re: Brooklyn). One is a day of meditation, guilt-admission, and conversation with the higher spirit, the other of debauchery, hedonism, and consumption of spirits. I could hardly participate in both.

And if I had a choice of observing either Yom Kippur or my 21st birthday, it seems obvious that the Hebrew option might make more sense – it’s the more moral and thoughtful thing to do. And while I only turn 21 once, I’ll still be able to celebrate and drink the next day when it’s not Yom Kippur. It’s also safe to say that more people have come to regret an extra vodka tonic than an extra musaf service. If Sandy Koufax refused to participate in the quintessential American past-time, surely I could postpone participating in the second most quintessential one. But still, choosing Yom Kippur wasn’t wholly satisfying (and not just because of the hunger) – I felt like I was ignoring another part of my identity, even if it was the part given to excess and gluttony. Yet I knew skipping shul to head out to bars would be equally, if not more, unfulfilling.

As the service came to a close – maybe during Avinu Malkeinu or the Tekiah G’dolah – I underwent a mental paradigm-shift and was able to reconcile what could have ruined the day. The fact that I had such an involved and impassioned inner dialogue made real the dialogue about accommodation, assimilation, tribalism, belief, and personal values that the greats like Moses Mendelssohn, Isaac Mayer Wise, and Mordecai Kaplan engaged with. It taught me that each conflict between traditional loyalties and modern enticements, whatever side is eventually taken, involves a deep engagement with and questioning of my Jewish and American identities – and in the process makes me more passionate and committed to each. The ambivalence and inner conflict was my first step into fully realizing what it means to be a Jew in the modern world. And let’s be honest – that’s all any 21-year-old wants for their birthday.

But the conflict – valuable in its own way – was not the sole product of my unique predicament. Despite their differences, Yom Kippur and turning 21 both involve an assumption of responsibilities. For both, the powers-that-be grant a certain level of trust and expectation that I will be a moral and responsible person in the year(s) to come. This dual burden is also an opening of horizons, however – I am given a clean slate to be the kind of adult and the kind of Jew I want. Because these two events fell on the same date, it seemed fated that I should forever be aware of my dual identity by being fiercely proud and seriously engaged with it.

Max Daniel is Editor in Chief of The Columbia Current.

[fbshare type=”button”]