Last winter, I attended the second Occupy Oakland port shutdown, along with hundreds of other students. At a midday rally, Angela Davis, one of my greatest heroines and a professor of my alma mater, addressed the crowd. My heart soared as she spoke of the “wins” of the first port shutdown.

However, my beating pulse came to a halt when she applauded the first shutdown for successfully blocking an Israeli ship from docking at the port. She called Israel an apartheid state. Everyone around me, including my friends and peers from school, immediately cheered. I, on the other hand, I was devastated.

I’m a Jewish Zionist, but it is often difficult for me to argue with Davis’ criticisms. On one hand, I desperately want to express my support for the Jewish state. But on the other hand, I am angered by the illegal occupation and human rights violations in Israel.

This spring, I graduated from the University of California-Santa Cruz. At the beginning of my senior year, two members of University of California President Marc Yudof’s Advisory Council on Campus Climate, Culture, and Inclusion embarked on a year-long project to identify “the challenges and positive campus experiences of Jewish students at UC.”

In July, the team released a report detailing the results of its project, including several suggestions for how the UC can make campuses more inclusive for Jewish students. The 10-page report claims that criticism of Israel on campuses has begun to threaten Jewish students. It asks the UC to sponsor a balanced perspective in the classroom and to revise their hate speech policies in order to make the UC “a more welcoming place for Jewish students.”

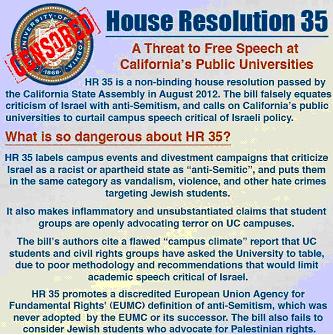

In August, the California State Assembly passed a bipartisan resolution, called HR 35, in support of the UC Council Climate team’s report. There was no debate prior to the resolution’s passing, and Israel wasn’t even mentioned during the introduction to the resolution.

While reading the UC report and the CSA’s resolution, I wondered if it is my university’s or government’s responsibility to protect Jewish students from criticism of Israel. If not, whose responsibility is it?

One of the things I learned when I came to UCSC is that there are many Jewish students who are not Zionist, and in some cases anti-Zionist. If the UC takes the report and the resolution seriously, then future students will not be able to make the distinction between Jewish identity and Zionism.

It’s not the UC or the CSA’s job to defend Israel. Rather, the American Jewish community—my community— should be working towards more politically-conscious education about Israel.

The most problematic aspects of the UC report are its recommendations. Two in particular stand out:

Recommendation 1: The UC should sponsor a balanced perspective in the classroom, and take action on speech that is intimidating for Jewish students.

According to its current hate speech policies, the only kind of speech that the UC will not tolerate is that which threatens physical safety. The report states that “…no students indicated feeling physically unsafe on UC campuses.” If the report were sticking to the UC’s current hate speech policies, it would end here. However, the report continues, suggesting that there are other forms of speech should also not be protected, such as criticism of Israel or Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state.

Jewish Zionist students at the UC make valuable contributions to the report, but our experiences are not the only ones that matter. There are other students, including non-Zionist or even anti-Zionist Jewish students, whose voices would be silenced if the UC took the report’s recommendations seriously.

Recommendation 2: The UC should accept the “legal challenge” of revising their hate speech policies.

This recommendation subtly implies that the UC would be brave to silence Palestinian solidarity groups. But the report isn’t really asking for bravery. It’s asking for an unfair amount of protection of Israel supporters, while ignoring the silencing of Palestinian solidarity groups and their allies, many of whom are Jewish students themselves.

The CSA’s HR 35 resolution takes the UC report’s recommendations seriously. In fact, the resolution goes a step further, applauding the UC for attempting to prevent anti-Semitism by refusing to participate in the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions campaigns on companies doing business with Israel.

But there is a very important word missing from the terminology of the CSA’s resolution: the students it seeks to protect are Jewish Zionists. The resolution makes no distinction between Zionist, non-Zionist, and anti-Zionist Jewish students, thereby conflating Jewish identity with Zionism. In doing so, the CSA is choosing sides in a political debate.

It’s no question that I, and many of my Jewish peers, feel intimidated when Israel comes under attack. This pain is legitimate and merits close examination. Nobody deserves to be victimized. At the Occupy Oakland port shutdown, I felt like I didn’t belong in the crowd because of my views regarding Israel, and that wasn’t okay.

But the problem does not lie with the UC’s lack of a “balanced perspective” in the classroom or its policies on hate speech. The problem lies within the American Jewish community itself.

It’s not that the UC report or the CSA’s resolution are completely useless; quite the opposite. They reveal a problem with Jewish education vis-à-vis Israel. The report states, “…it is clear that for many Jewish students, their Jewish cultural and religious identity cannot be separated from their identity with Israel. Therefore, pro-Zionist students see an attack on the State of Israel as an attack on the individual and personal identity.”

This lack of distinction between Jewish identity and connection with the state of Israel is not invalid, but it does indicate a cognitive dissonance that the American Jewish community must confront.

To be a Jew in the United States today is to acknowledge that we hold an extraordinary level of privilege, and with that privilege comes responsibility. In Hebrew school and synagogue, I inherited an intense spiritual connection to an ancient homeland. But when I came to UC Santa Cruz, I learned that the Jewish state is no longer simply a promised land of milk and honey; it is also a nation-state that must face the same challenges that every state faces.

There are over a thousand years missing from mainstream Jewish education, in regards to Israel and Zionism. For instance, until I went to college and majored in Jewish studies, I had no idea that Zionism was a massive social movement in Eastern Europe, or that there were other key Zionist leaders aside from Theodore Herzl. I had never heard of AD Gordon, Ahad Ha’am, Ber Borchov, or Nachman Syrkin. And what if Yom Ha’atzmaut were more than just a picnic in the park, but included an analysis of the mass exodus of Palestinians from the new state? What if Birthright trips were to send carefully selected delegations of Jewish students into the occupied territories of the West Bank?

I am calling on the American Jewish community—my community—for a more conscious education of Israel’s history, culture, and politics not only as an idea or a dream, but as a modern nation-state.

Please sign this petition in order to encourage Yudof to disregard the UC report on campus climate for Jewish students. If you are a student at a higher education public school in California, please sign this petition.

Shani Chabansky is a freelance journalist in the California Bay Area and an editorial intern at Tikkun Magazine. She recently graduated from the University of California, Santa Cruz with a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and as a member of UCSC’s inaugural class of Jewish studies majors.